Sunday 11 May 2025

Leicestershire’s Notorious Outlaws: George Davenport

LAHS Member Steve Marquis tells the story of an 18th Century Highwayman from Wigston.

George Davenport, Leicestershire’s Highwayman, is the subject of this blog, the third and last in a series of three telling the stories of Leicestershire’s Notorious Outlaws. Born in Wigston Magna in 1759 and executed at the Red Hill gallows in 1797, George Davenport certainly lived his short life to the full as we shall see.

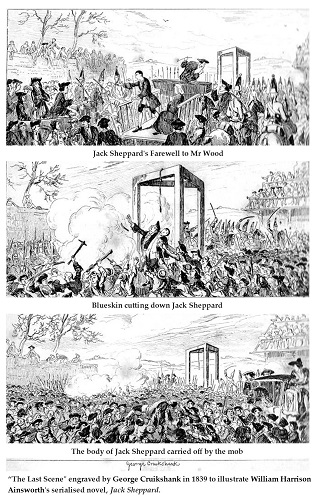

George Davenport was Leicestershire’s very own Dick Turpin or Jack Sheppard (the two most infamous 18th century highwaymen) who for eighteen years roamed the nocturnal roads of the county mugging travellers until captured and hanged in 1797. As already mentioned in previous blogs, it was not unusual, especially in the centuries prior to 1800, for the poorest in the land to romanticise, even idolise, famous contemporary outlaws seen as rebelling against a corrupt and unjust system. This was certainly the case for Turpin and Sheppard whose executions were witnessed by huge, largely sympathetic crowds (for Sheppard’s hanging as many as 200,000 people attended, one third of London's then population). Novels, plays, and later films glorifying their deeds have continued to be produced right up to the present day. The legend of Robin Hood itself grew out of this desire of the oppressed over several centuries to see one of their own turn the tide on their oppressors by robbing from the real ‘robbers’ i.e., the thieving ruling classes.

It is not difficult to understand where this alienation derived from, during the second half of the 18th century as the agricultural and industrial revolutions were plunging ever increasing numbers of people into abject poverty. This was the peak period for the ‘legal’ enclosure of what remained of the medieval open-fields and common land, forcing extremely poor, yet formerly semi-independent, peasants into the servitude of wage labour or, more often than not, off the land altogether, usually into the misery of emerging slums in the rapidly growing industrial conurbations. Thus, a way of life that had included the vast majority of the population for eight centuries completely disappeared within a single lifetime, depriving hundreds of thousands of peasant farmers of their traditional means of subsistence and driving them into total destitution. This, and the widespread use of capital punishment or transportation for minor offences, had brought the law and court system into disrepute amongst the poorest sections of society. The idea of robbing from the rich and giving to the poor was very appealing to those at the bottom of the social heap.

Unfortunately, this idealised view of the ‘virtuous outlaw’ was rarely true and especially questionable in this case of George Davenport, whose victims were ordinary people and it is clear that the main beneficiaries of his ill-gotten gains appear to have been Leicestershire innkeepers.

Baptised at All Saints Church, Wigston Magna, on 5 November 1759, an appropriate date, his later entry into the adult world was certainly explosive. Coming from a reasonably well-to-do family, George had some schooling. His teacher, a Mr Siddons, described him as a “ready boy, willing and quick to learn”. On leaving school around the age of thirteen, like many young locals at this time, George became a framework knitter’s apprentice. He quickly acquired a reputation for being a bit of a ‘Jack the Lad’ (a slang term first used to describe Jack Sheppard). George seems to have involved himself in petty crime from a young age: "he associated with young men of immoral and libertine habits, with whom he soon became, if not the chief of drunkards, almost the chief of wrestlers, bowlers, jumpers and the like." [1]

Amongst his first criminal activities was the ploy of ‘taking the King’s shilling’ and joining the army. After a drinking session with the soldiers who recruited him, he would "bolt in the night”, often on one of their own horses. He later confessed to having done this forty times. On one occasion, however, his luck ran out and he was caught after absconding from Nottingham’s 40th Foot Regiment, resulting in him being sentenced to 600 lashes but was said to have received only 300 after the overseeing officer shouted: “Stop, it is in vain to punish him anymore – he has no feeling.” It is very unlikely he would have survived the full 600 lashes. Six hundred lashes seems extraordinarily severe, even 300 would likely have been life-threatening for many. This, and other evidence, reinforces the notion of a strong and powerful man. In one Leicester Journal report (25/2/1794) he was described as being “about 5 feet 8 inches high, pitted with the smallpox, light brown hair….”

George did, however, manage during his ‘on and off’ military career to actually serve for a spell in the Leicestershire Regiment and was sent to fight for ‘King and Country’ in the American War of Independence. He was even promoted to corporal, but his penchant for drinking and petty thieving soon saw him in trouble. The final straw was to go absent without leave in order to visit a girlfriend while supposedly on guard duty – he was quickly reduced to the ranks. When stationed in Plymouth, he and some friends would sneak out of the barracks to waylay and violently steal from drunken sailors. Being the main suspect for these crimes, George went on the run but was captured, court-marshalled and dishonourably discharged from the army. He now returned to Wigston in 1779 aged twenty and began his career as a highwayman.

Local tradition in Wigston has it that he used a cottage on the Leicester Road as a hideout, behind which was a bakery and in its loft a gunstock and bridle were later found which were thought to have been his. One known associate and probable ‘fence’ who likely passed on the stolen loot was Thomas Ross, the landlord of an inn on the London Road in Oadby, possibly called the ‘Woolpack’. Another Wigston legend has him regularly performing a jig on the roof of The Old Crown Inn, which he called the "Astley's hornpipe." (probably named after a friend).

At some stage after arriving back in Wigston he married a Loughborough girl called Elizabeth, with whom he would have six children, sadly, three died in infancy, including their first two sons who passed away within six months of each other in 1790. Their last child, a daughter, was born after he was executed. Left alone for much of the time while her husband was out thieving and drinking, plus frequently being forced to go on the run for months at a time, Elizabeth must have found life exceedingly difficult with no regular income, an often-absent husband and thus, on occasion, was recorded as living “off the parish”. Yet, the correspondence between them at the time of his execution suggested that a loving and affectionate relationship had endured despite all the hardship (see below).

Early in 1794, George and another Wigston lad, William Lawson, attempted to rob a Mr Thornloe on the Narborough Road. The victim’s cries for help were heard and people nearby came to his aid. George escaped but the abandoned Lawson, described as a “cripple”, was caught. For his involvement William was sentenced to seven years transportation.

'On Saturday night last, about eight o'clock, as Mr Thornloe was returning from Leicester market, he was attacked upon the Narborough road by footpads, one of whom he knocked down with his stick, and some person fortunately coming up at the moment, secured him; the other escaped. Wm. Lawson, the person in custody, has impeached his accomplice, George Davenport of Wigston, who has absconded.'

Northampton Mercury 1 Mar 1794.

Although the Leicester Journal had similar reports on George Davenport’s activities, the Northampton Mercury accounts are of a better quality.

Later that year, George and two companions were arrested on the suspicion of stealing silver tankards from alehouses in Leicester’s Humberstone Gate area. Whilst waiting for his trial on 12 August, all three escaped from the borough jail in the Guildhall. His situation was now far too hazardous locally, so he fled to the anonymity of London’s teeming crime-ridden backstreets around St. Paul’s Cathedral. But, even in the metropolis his exploits were soon gaining some notoriety, so he used the name of one of his previous victims, a ‘George Freer’. The author of his biography written shortly after George’s death, described the robbery of George Freer which had occurred early in his criminal career: -

'He again determined to prosecute his old course; and sometime after robbed a poor labouring man, of the name of Freer, upon Clack-Hill, of the sum of 40 shillings.'

As George Freer, he quickly became an active member of the capital’s criminal fraternity. One story again reveals his obvious physical strength and astute if somewhat seedy character. After a particularly lucrative robbery, George and his accomplices settled down to a game of cards in which he lost all his share of the spoils. He may have felt cheated because he later accosted the main winner, knocking him out and retrieving even more than his original stake. The victim had no idea that one of his own gang had mugged him and was apparently just relieved to have escaped with his life.

George Davenport’s stay in London lasted for eighteen months during which time his reputation as a dashing highwayman grew, he even acquired that romantic highwayman cliché of the ‘gallant gentleman robber’ when stealing from attractive women. On one occasion after flirting with an embarrassed victim on the Edgeware Road, he was said to have requested a kiss and then concluded their meeting with: “Now madam, I must insist on being paid for my trouble” and walked away with four guineas.

After his long sojourn in London, George again returned to Elizabeth and Wigston in 1795, where he seems to have felt safe and confident of not being betrayed by his neighbours. Whether this was a result of local loyalty or intimidation we shall never know. A year later he was finally betrayed by the landlord of the Old Crown Inn, Mr Barnes, who, along with another villager, handed him over to the law, which might be a clue as to the true local feelings towards him, or they may have simply done it for the reward. It appears they took advantage of the situation when George became incapacitated after falling into a drunken stupor.

On 22 July 1796, George was charged with the capital offense of highway robbery. Yet again, his good fortune held as he was acquitted of the capital offence on the legal technicality of a ‘statute of limitations’, the crime having occurred more than two years before. He was, however, rearrested for the lesser offence of one of his many military desertions and returned to Leicester Gaol to await a transfer to Chatham Barracks, from where he was to be transported to the West Indies – a virtual death sentence.

'George Davenport, Daniel Dixon, Joseph Smith, Elizabeth Digby and Thomas Furborough were tried on different charges, but acquitted.' Northampton Mercury 30 Jul 1796.

George now faced an even greater threat than transportation, having been put in a cell with an ex-accomplice, a cork seller, waiting to be tried on a capital charge. With the authorities now desperate to be rid of their troublesome highwayman, he was in real danger that the cork seller might save his own skin by turning King’s evidence against his former associate. Once again, the quick thinking of a calculating if callous mind came to his rescue. George managed to convince his cellmate that those deemed insane always avoided the ‘drop’. Incredulously, he was able to persuade the cork seller that by threatening to hang himself he would be declared mentally incapable and reprieved, at least temporarily. To achieve this, they devised a plan in which the cork seller would pretend to hang himself and George would raise the alarm and save him. Of course, he just left him hanging there, thus problem solved – though hardly the actions of a ‘Robin Hood’. George was soon transferred to Chatham Barracks but managed to escape yet again and returned to his home village. It would be interesting to know how Mr Barnes fared on his reappearance.

Now convinced of his own infallibility, he became even more reckless and violent as his crime spree rapidly escalated. Amongst his victims at this time were, coincidentally, two butchers who, on separate occasions, were severely beaten and had their lives threatened, one on his way home from Belgrave and the second whilst returning to Blaby.

Other stories during this period, include robbing an old man he had been sharing a drink with and who foolishly confessed to keeping his money in his shoes, just in case he was confronted by George Davenport. On another occasion whilst drinking in the Bull’s Head, Belgrave, a group of patrons were looking at a poster offering a reward for his capture and speculating on ways he might be caught so they could claim the reward. George brazenly declared “I’m George Davenport, catch me if you can”, then darted out through the backdoor and escaped over the garden wall.

Like many notorious criminals, George’s eventual downfall was brought about in the most banal of circumstances. Under his alias, ‘George Freer’, he had been caught illegally fishing near Blaby. Unwilling or unable to pay the fine of £5 (a substantial sum then), he was held on remand and sent to Leicester to await trial. On the journey, George and the officer accompanying him, stopped off for a drink at the Saracen’s Head. There he was recognised, and his escort suddenly found himself in the company of the most wanted criminal in Leicestershire. Fortunately for the officer, his prisoner was still in irons. This time the authorities were determined he would not escape again.

His trial took place on 11 August, the case for which he was prosecuted related to the robbery of a Mr Sutton, landlord of a pub in Kegworth, whom George and five others had waylaid on his return from Derby market. Mr Sutton identified George Davenport as the main perpetrator. There was little doubt what his sentence would be because even those convicted of relatively minor offences, including children, were regularly executed during this period. It appears that George dealt with his impending demise stoically by embracing religion and convincing himself he was about to transcend to a worldly paradise, despite his sinful life. In one letter to his wife, he wrote: -

'My most gracious beloved,

I am going from a prison to a palace, I am going to heaven, where are three of my babies, and leaving thee on earth where are three of my children…'

In another he wrote: -

'Dear wife, farewell, I will call thee wife no more, yet I am not troubled for now I am going to meet the bridegroom the Lord Jesus, to whom I shall be eternally married. Thy dying yet affectionate friend.'

George Davenport, Leicester Jail.

He was hanged on the Red Hill gallows (A6 just before you reach Birstall) on 28 August 1797, one witness, a schoolgirl, wrote in her diary that: “George Davenport was hanged on Monday…, we saw him go by in his shroud.” Defiant to the end, George apparently deprived the executioner of obtaining any of his personal belongings by unusually wearing the shroud over his clothes and possessions. The custom was that a hangman could claim any of the personal effects of an executed criminal found ‘outside the shroud’.

Another witness to the execution was a reporter from the Leicester Journal, who gave a vivid account of what he witnessed: -

'His deportment on the morning of his fatal exit was manly and decisive, - nor did his fortitude for a moment forsake him. Dressed in his shroud and surrounded with all the paraphernalia of death he acquitted himself as a humble and penitent sinner looking anxiously forward towards another world for the consolation which his devotional exercises had given him reason to expect. He fully acknowledged the justness of his sentence as well as the crime for which he suffered. After remaining for some moments in prayer he gave the fatal signal and was launched into eternity at about one o'clock in the afternoon.'

George Davenport was later buried in All Saints’ churchyard, Wigston, although the parish records give the date of interment as 14 February 1798, six months after his execution, possibly indicating that his body may have been left to rot in a gibbet, as was customary at that time.

Whilst Dick Turpin and Jack Shepperd can be placed on the long list of popular outlaws, George Davenport, unsurprisingly, has never been seen in the same light. What then are the criteria necessary to get on that list?

Many outlaw/rebels led revolts against their oppressors and became popular heroes. For people suffering tyranny or struggling economically, those seen as rebelling against their oppression were viewed by many as heroic figures offering a kind of defiant dignity against the all-pervasive humiliation of being poor and powerless, providing an alternative reality, a form of escapism, even if usually only a fantasy.

Steve Marquis stephen.marquis@ntlworld.com

Sources

1. A short biographical publication written shortly after Davenport’s death and is a major source for what we know about his colourful life. How accurate and authentic is another matter.

2. Barry Lount’s excellent book on George Davenport, published in 1983 by the Oadby Local History Group.

Both these books are out of print and very difficult to obtain. Although the Greater Wigston Historical Society has a copy of the biography published in 1797, GWHS Transactions 46. Any readers interested would need to contact the GWHS for access.

3. Many local contemporary newspaper reports provide a great deal of information about Davenport’s escapades.

This blog is the third in a series of three on Leicestershire's Notorious Outlaws. The other two are are on Roger Godberd and The Folvilles.

Silhouette of a Highwayman. © Pub History Project - Leicester (2021) https://pubhistoryproject.co.uk/2021/01/14/saracens-head-molly-o-gradys-knight-garter-hotel-street/