Sunday 9 February 2025

Leicestershire’s Notorious Outlaws: Roger Godberd

LAHS Member Steve Marquis explores the aftermath of Simon de Montfort’s rebellion and the origins of the legend of Robin Hood.

This blog looks at the life of Roger Godberd, Leicestershire’s ‘Robin Hood’ who lived in the 13th century, and is the first in a series of three on Leicestershire’s Notorious Outlaws. The second, will describe the exploits of the Folvilles, Leicestershire’s Gangster Family of the 14th century. The third and final piece, will cover the criminal career of George Davenport, Leicestershire’s 18th century highwayman. This series will also explore the worldwide cultural phenomenon of the ‘popular outlaw’.

Roger Godberd: Leicestershire’s ‘Robin Hood’

It is somewhat surprising considering that the vast majority of people are the victims of crime and only an extremely small proportion are serious perpetrators. And yet, virtually every society has their own examples of ‘popular’ outlaws who figure prominently in their cultural landscape. I’m sure most people reading this blog will have heard of some, if not all, of these examples of famous outlaws: William Tell, Dick Turpin and Jack Shepperd as well as Ned Kelly, Billy the Kid, Jesse James, Pancho Villa, Bonnie and Clyde, to mention just a few. Fewer readers will be familiar with legendary outlaws outside the western world such as Song Jiang of China or Tantia Bhīl from India. I shall explore this worldwide phenomenon further through the three cases covered in this series.

Of course, by far the most important popular cultural icon and literary figure in this country is Robin Hood and now probably the most famous and renowned outlaw on the planet.

.jpg)

Robin Hood: man, or myth? A question that has still not been definitively answered even after centuries of endless debate and research. While we cannot be certain if there was an actual historical figure at the centre of the Robin Hood legend, there have been numerous candidates put forward as possible contenders. One of those regularly mentioned in this regard is Leicestershire’s Roger Godberd, who fought alongside Simon de Montfort at the battles of Lewes (1264) and Evesham (1265) and became an outlaw (for the second time) after Montfort’s defeat. Some of the earliest accounts of Robin Hood link him with Simon de Montfort’s Rebellion (see below), including Roger Godberd.

Roger Godberd was born around 1230 into a family of substantial landholders at Swannington, northwest Leicestershire. His father died when Godberd was very young, so control of the estate passed to his mother and shortly after a stepfather. Roger was unhappy with some of their actions, which led to disputes and a lot of bitterness towards his parents.¹ Godberd was a tenant of the mercurial and impetuous Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby, who in 1260 came of age and began a long-drawn-out battle for control over his inheritance with Lord Edward, the future King Edward I, who had acquired wardship of the estate on de Ferrers father’s death. Edward had sold his wardship to Peter of Savoy for 6000 marks which de Ferrers resented.

Roger Godberd became an outlaw in the same year because of a dispute with Jordan le Fleming who had rented Godberd’s lands while he served at Nottingham Castle during de Ferrers’s first revolt against Lord Edward, but le Fleming refused to return the estate when that service ended. Godberd then attacked le Fleming, forcibly removing him from his property.

When the barons’ rebelled against Henry III in 1263, Godberd joined the revolt alongside his liege lord (as a tenant he would most likely have been obliged to offer military service to de Ferrers) and was presumably pardoned after Simon de Montfort’s victory at Lewes. Having survived the slaughter at Evesham twelve months later, he seems to have joined the resistance that continued in several places, including at Kenilworth Castle, for a further two years.

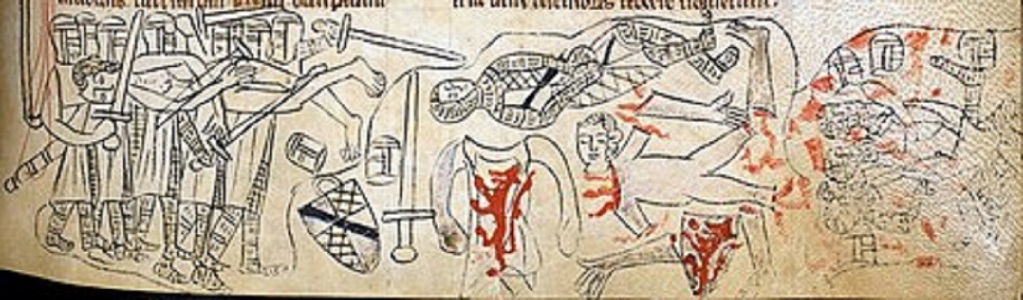

The battle at Evesham in 1265 was particularly ferocious.

“having killed Montfort by driving his lance through his throat, Roger Mortimer had not finished. He set his men upon Simon’s broken body. They cut off his hands and his feet. They hacked off his head and cut off his testicles and stuffed them into his mouth. This prize was sent by Mortimer back to the Marches, as a present for his wife.”²

Inflicting such humiliating butchery on fallen members of the baronial class was highly unusual in medieval warfare, demanding a ransom was the more customary response (perhaps rebelling for the people rather than baronial interests was just beyond the pale). For defeated armed peasantry such slaughter was normal practice. Many men from Leicestershire, both free and unfree, would have died alongside Simon de Montfort.

How genuine Simon de Montfort’s commitment was for the political reforms he introduced during his brief reign is impossible to now ascertain, but what is certain is the widespread enthusiastic support this French baron received from the lower orders. The events at Peatling Magna, just days after the defeat at Evesham, and at Stoughton in 1278, where small peasant communities challenged the power not only of local nobles but the authority of the state as well, were both representative of a new spirit of resistance and growing political awareness amongst the peasantry that had penetrated deep into the ‘community of the realm’ after Magna Carta, reinforced by Montfort’s Rebellion.³ A growing sense of grievance and alienation that would continue to fester until that resentment burst forth in the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381.

Godberd again lost his lands after Montfort’s defeat and was once more declared an outlaw by King Henry. Although pardoned in October 1266, he was unable to afford the heavy penalties needed to regain his estate and once again chose banditry as a means of solving his financial difficulties.

Little is known of Godberds’ felonious exploits until his capture and escape in 1271 from Nottingham Castle aided by Sir Richard Foliot, a fellow supporter of Montfort. Sir Richard Foliot resembles ‘Richard at the Lee’, a character who first appears in the Gest of Robyn Hode. It is likely that in the previous five years, Godberd led a gang of fugitives whose criminality was mainly centred on Sherwood Forest; another factor in him being linked to Robin Hood. ⁴

In the Curia Regis Rolls, Godberd is described as a ‘valletus’ or valet, “though the term didn’t have the same servile meaning as now. Rather, it was used to describe a man of the middling sort who might otherwise be called a sokeman or yeoman.”⁵ And yet, the abundance of evidence suggests Godberd was far more than just a common outlaw that his relatively lower social status would normally have condemned him to be. His extraordinary acquittal on the instructions of Edward I at his trial in 1276, just four years after his possible involvement – perhaps even as a leading figure – in the 1272 rebellion against Edward whilst he was on Crusade in the Holy Land, is still an unfathomable mystery. The events of this rebellion were described in the Flores Historiarum: -

“Some persons in England, kindling with envy and rage, thirsting for money that didn’t belong to them, and prophesying of their own hearts, affirmed that Edward would never return to England. These men, wishing to make sure of future events, collected in the northern provinces some three hundred men, without counting infantry and light-armed cavalry…” ⁶

These rebels aren’t named, but Godberd and his men were captured in Sherwood Forest in 1273 at the same time the rebellion was crushed by Roger de Mortimer and Lord Edmund, younger brother of Edward. The troops that seized him were led by Sir Reginald de Grey – the Sheriff of Nottingham during Godberd’s exploits in Sherwood Forest – who had led a large force with the specific task of apprehending him. Godberd’s lieutenant, Walter Devyas, was executed immediately but Godberd was taken prisoner and placed under the control of Mortimer. Described as the ‘leader and master’ of the outlaws in the Midlands, he may even have been one of the key figures in the conspiracy, which may explain the large force led by Grey to capture him.

The fact that there was at least one attempt to rescue him from Mortimer’s Bridgnorth Castle gives further credence to his significance. Another incident of note occurred in Leicester where Godberd’s brother Geoffrey and others attacked members of Sir Reginald de Grey’s household, presumably in retaliation for Grey’s arrest of Godberd. It seems this attack had the support of the abbot of Leicester Abbey, so, there might have been more to it than just the arrest. Sir Reginald de Grey, a supporter of Henry III against Simon de Montfort, had clearly fell out with the Godberds at some stage. ⁷ Again, suggestive that Godberd was more than just a simple outlaw.

After his arrest, he spent three years in various prisons awaiting his trial. Godberd was accused of committing burglary, robbery and arson, mainly in Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire, but also as far as Wiltshire, where a travelling party of monks from Stanley Abbey were violently attacked, killing one of its friars and stealing a large amount of money. But as already mentioned, he was unexpectedly pardoned by Edward I. The explanation for this remarkable leniency still remains a mystery. What happens to Godberd next is also somewhat of a mystery, with one report saying he died in Newgate prison in 1276, whilst another, probably a more credible record, states his death took place on his Swannington estate in 1293.

Following the defeat of Simon de Montfort and the obvious widespread feelings of despair and resentment it generated amongst the lower orders, lawlessness greatly increased, with many of the surviving rebels forming or joining outlaw gangs. Thus, generating some of the earliest stories of the Robin Hood legend that would become the mainstay of later narratives.

Roger Godberd provided quite a few: being based in Sherwood Forest; his encounter with a Sheriff of Nottingham; being saved by a sympathetic knight called Sir Richard; hostility to the church hierarchy, led to the idea of him being seen as a potential historical Robin Hood. Walter Bower in his Scotichronicon (history of Scotland written during the 1440’s), nearly two centuries after the Battle of Evesham, along with another Scottish writer, Andrew de Wyntoun circa1420, were the first chroniclers to place Robin Hood amongst the ‘Disinherited’ a contemporary description applied to Simon de Montfort’s many followers after his defeat.⁸ Bower claimed that Robin Hood became an outlaw in the aftermath of this battle but didn’t name a specific candidate. This association led many later commentators to link Godberd to a potential historical Robin Hood.

“At this time there arose from among the disinherited and outlaws and raised his head that most famous armed robber Robert Hood, along with Little John and their accomplices. The foolish common folk eagerly celebrate the deeds of these men with gawping enthusiasms in comedies and tragedies and take pleasure in hearing jesters and bards singing [of them] more than in other romances.” Walter Bower

The Legend of Robin Hood

Robin Hood the outlaw was clearly an extremely popular figure by the 14th century, the period in which many ballads and poems emerge associated with Robin Hood, having been first mentioned in William Langland’s poem Piers Plowman circa1377. Yet clearly, his folk hero status goes much further back than that amongst the poorer sections of society.

Any earlier stories about a ‘people’s outlaw’ would have been oral tales spoken in Middle English and not written down until Piers Plowman and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (written between 1387-1400) had appeared as the first major literary works composed in the ‘people’s language’, which gradually ended French dominance over the nation’s literary culture. Being a folk hero of the peasant classes would have had little appeal to the ruling elites reading their chivalric romances written in French.

One of the earliest and most detailed account of the escapades of Robin Hood was the ballad A Gest of Robyn Hode, a series of individual tales, and although the earliest printed editions date to the first decades of the 16th century, the eight surviving versions of the Gest were probably compiled around 1400. It is likely that the Gest stories were based on several outlaws’ activities, including a Robin Hood of Wakefield who, according to Joseph Hunter, became an outlaw following the failed rebellion led by Thomas Earl of Lancaster, Leicester and Derby against Edward II in 1321-22. This was, of course, the period in which the Folvilles were also active, the subject of the next blog in this series. There are several historical references in the Gest that place its Robin Hood in the first half of the 14th century. Although these early accounts of Robin Hood indicate that he was of the lower yeoman class, like Roger Godberd, it’s unlikely that the earliest oral tales would have been based on a specific historical figure.

By the end of the 15th century, Robin Hood was well-established as a cultural icon (to use a modern idiom). In 1473, Sir John Paston writes to his brother that he had paid a servant to act in plays about Robin Hood: “I have kept him these three years to play Saint George and Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham.” Paston then complains that the said servant had run off to Barnsdale of all places without apparently recognising the irony of the situation. ⁹ Dances and pageants featuring the Robin Hood story increasingly became part of village annual Wakes Day and May Day festivities. Henry VIII was clearly a fan, he paid twelve actors to perform a Robin Hood dance as part of his coronation celebrations.¹⁰ Six years later in 1515, Henry organised a pageant when much of his court were “met by a company of yeomen clothed in green with bows, whose leader Robin Hood desired the king and queen to come into the green wood to see how outlaws lived.”¹¹

It is now that Robin Hood ceases to be a common man fighting on behalf of his own class against grasping nobles and churchmen, instead he becomes ‘Robin of Locksley’, a wronged nobleman himself waging a campaign of class collaboration of fair treatment for all that was being denied by ‘bad’ Prince John (although universally known as ‘Prince’ John this title didn’t exist in England at that time) and in support of ‘good’ King Richard. This naive faith in ‘beneficent’ kingship providing justice for the common people and protection from rapacious elites would have disastrous consequences for would-be outlaw rebels, leading to many defeats and executions, as William Wallace and Wat Tyler could testify to.

The earliest recorded Robin Hood-like figure, actually from the period of King Richard and Prince John, was William fitz Osbert, son of a London clerk, who during the 1190’s led mass protests of London’s poorer citizens against the enormous burden of financing literally a ‘king’s ransom’ to secure the release of Richard from captivity after being seized by Duke Leopold of Austria whilst returning from the Third Crusade. William fitz Osbert himself had also joined that crusade, returning home in 1190.

There are certainly aspects of fitz Osbert’s activities that find echoes in later Robin Hood stories, e.g., his going on crusade with Richard, his championing of the poor and popular veneration after his execution. William fitz Osbert was yet another victim of the belief in a ‘good king’, focusing his protests against Prince John and appealing to King Richard, just like Errol Flynn in the classical 1938 film The Adventures of Robin Hood.

John Maddicott suggests that by at least the 1260’s the name ‘Robin Hood’ had become synonymous and widely applied as a generic term to describe anyone deemed an outlaw.¹² This implies a very long gestation period in the evolution of an extremely popular, yet likely, fictitious character, hoovering up storylines over decades, even centuries, from many real or imagined heroic fugitives, all embodying ordinary people’s many grievances and aspirations for their redress. Simon de Monfort’s rebellion had further radicalised an already disgruntled and resentful peasantry, the defeat at Evesham only heightened the alienation and class enmity towards the governing elites. The early decades of the 14th century, during the egregiously corrupt reign of Edward II and the appalling lawlessness in the aftermath of the Great Famine, saw again a proliferation of Robin Hood stories as contained in the Gest of Robyn Hode. Similarly, the first written accounts of Robin Hood coincided with the Peasant’s Revolt, emphasising the connection between intensifying class conflict and the surfacing of tales of popular outlaws turned rebels. It is hardly surprising that such periods would have fostered the kind of romanticising, even idolisation of famous outlaws seen as rebelling against a venal system.

Lythe and listen, gentlemen.

That be of free born blood;

I shall you tell of a good yeoman

His name was Robyn Hode…

… he was a good outlawe,

And dyde pore men moch good.

From the Gest of Robyn Hode

Steve Marquis 2025. Email: stephen.marquis@ntlworld.com

Notes and References

1. Chris Thornycroft, Roger Godberd of Swannington, English Historical Fiction Authors, 10/4/2018.

2. Sophie Thérèse Ambler, The Song of Simon de Montfort: England's First Revolutionary, Pan Macmillan (2020), page 383.

3. The extraordinary events at Peatling Magna and Stoughton, where the villeins actually had the audacity to challenge their landowner’s (Leicester Abbey) decision to increase their feudal obligations. That challenge amounted to the taking of the abbot of Leicester Abbey to the king’s court by his tenants, who claimed they should be exempt from such onerous labour services because of their status as “sokemanni” i.e., freemen. Just two examples of growing political consciousness amongst the labouring classes that developed during the 13th century. For more on the incident at Peatling Magna, there is an excellent account in Michael Wood’s In Search of England, Viking Penguin Books (1999). The most detailed description of events at Stoughton was written by Rodney Hilton: A Thirteenth-Century Poem on Disputed Villein Services, English Historical Review LVI (1941).

4. David Pilling, The History Geeks, The Revolt of Roger Godberd, 3/10/2016.

“In the summer of 1264, while burning and plundering in the Midlands, Ferrars seized Nottingham Castle and installed his own men in the garrison. The names of these men are listed in the Patent Rolls, and among them was Godberd. While at Nottingham, Godberd and his comrades took the opportunity to indulge in some large-scale poaching in Sherwood Forest: in 1287, over twenty years afterwards, they were summoned to court to answer for this crime. Medieval justice often moved very slowly indeed, and several of the accused were dead by then.” See also David Pilling’s Origins of a Legend: Robin Hood and the Disinherited, Aspects of History, 2021.

5. ibid, Pilling, 2016.

6. ibid, Pilling, 2016.

7. ibid, Pilling, 2016.

8. Andrew de Wyntoun, Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland, circa1420.

9. Graham Phillips & Martin Keatman, Robin Hood - The Man Behind the Myth, Michael O’Mara Books (1995) page 4.

10. ibid, page 5.

11. op. cit., Wood (1999), page 72.

12. J. R. Maddicott, Simon de Montfort, Cambridge University Press (1996).

Robin Hood on a Horse. Woodcut c.1475. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robin_Hood#/media/File:Robin_Hood_on_a_Horse.jpg