Sunday 2 March 2025

Leicestershire’s Notorious Outlaws: The Folvilles

LAHS Member Steve Marquis examines the consequences of famine, political instability and lawlessness in the early 14th Century.

This blog is the second in a series of three telling the stories of Leicestershire’s Notorious Outlaws. In this episode we encounter the Folville Clan – Leicestershire’s ‘Gangster’ Family. The 14th century was worst period to have ever lived in England since the 6th century when as then, unprecedented famine, plague and wars devastated the country. From 1315 until 1322, the Great Famine caused mass starvation and a complete breakdown in law and order - out of the chaos emerged the Folvilles.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

“… a great Famine of Dearth with such mortality that the living could scarce suffice to bury the dead, horse flesh and dogs’ flesh was accounted good meat, and some ate their own children. The thieves that were in Prison did pluck and tear in pieces, such as were newly put into prison and devoured them half alive.”¹

Following the feast came the famine. After three centuries of relatively benign weather conditions, beginning around the year 1000 CE, during which harvests were generally good, helping facilitate a rapid growth in population that reached its peak of approximately four to five million by 1300, perhaps double that of 1086.

The catastrophic 14th century that followed would experience years of famine, plague and war as the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, well three of them, ‘famine’, ‘pestilence’ and ‘war’, would all make deadly appearances during the 1300’s. The fourth, ‘conquest’, had been and gone after destroying Anglo-Saxon England two hundred years before. The resulting desolation saw the population of this country reduced by as much as 50% and wouldn’t reach its 1300 level again for the next three to four hundred years.

Famine and severe food shortages were fairly common during the Middle Ages, yet clearly, the Great Famine of 1315-22 was of a different magnitude altogether in terms of its intensity and duration with long-term ramifications that would last for generations; and it can be argued began the process that would eventually bring about the end of feudalism. The existing system’s inability to cope with a crisis on this scale led to people beginning to lose confidence and faith in that system. Undoubtedly, the seeds of the later Protestant Reformation were sown in the traumatic and devastating 14th century.

To make matters even worse, the famine occurred during the reign of Edward II, a totally inept and corrupt monarch whose catastrophic rule caused a complete collapse in any meaningful governance to such an extent he was eventually usurped by his own wife. It was in this maelstrom that the criminal activities of the Folvilles would begin.

Medieval society was already far more violent and lawless than today, even before the dire 14th century. Lawrence Stone suggests that homicides in England during the Middle Ages were probably ten times higher than in more recent times. In 2023, the murder rate in this country was less than one in 100,000, in Oxford during the 1340’s the equivalent homicide rate was 110 per 100,000.²

William Hoskins wrote an account of a series of eight medieval homicides in Wigston Magna between 1299 and 1390, a high figure considering the population would have been less than a 1,000 at the time. Of the eight cases discussed, all those involved were from the village’s wealthier families, and all the perpetrators were eventually pardoned. ³ As only the records of those pardoned – i.e. the wealthier inhabitants – have survived, the number of homicides would likely have been much higher. There are additional clues as to the extent of this threat of lawlessness that medieval Wigston people – like the rest of the population – faced. For example, the name ‘Shakresdale’ meaning ‘robbers’ valley’, as the undeveloped area on the western side of the parish towards neighbouring Aylestone was called during this period. Another part of the parish was also referred to as ‘robbers’ pasture’. The fact that it was also the custom to have a regular local volunteer night-watch guarding over the village, which was revealed in the record of a coroner's inquest in Wigston of one of those night-watchmen who ''was accidentally killed during a contest with which they were whiling away the hours.” ⁴

With no police force, poor transport and communications, and little by way of national government or administration, it must have been relatively easy for criminals to escape retribution by fleeing the scene. Joining the army appears to have been one well used escape route. Travelling the roads was particularly dangerous, with many outlaw bands roaming the dense forests that covered much of the country and they were likely far less magnanimous than Robin Hood. Famines, plague and the threats posed by civil war, invasions and piracy were particularly dangerous for ordinary people. Whole villages might be put to the sword and burnt to the ground – making life during the Middle Ages generally “…poor, nasty, brutish, and short." (Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes). Never truer than in the 14th century.

The Folvilles – Leicestershire’s Gangster Family

Just as the country was slowly emerging from famine and the weather gradually improving, especially during the 1330’s, with a series of good harvests – any sense of relief and optimism for a better future was immediately undermined by an explosion in violence and lawlessness, with outlaw bands roaming the country and terrorising the population almost at will. Two of the most notorious criminal gangs were the Folvilles of Leicestershire and the Coterel gang in Derbyshire, who occasionally joined forces in carrying out their criminal enterprises.

The Folvilles were sufficiently infamous to get a mention by William Langland in his poem Piers Plowman circa1377 (decades after their banditry ended) alongside Robin Hood (in fact, the first literary reference to the famous outlaw): “…and fix it for false men with Folvyles law…”. The implication being that they followed their own rules and inflicted their own ‘justice’ on “false men”, and both were presented in a positive light in the poem. Though, the Folvilles could in no way be described as heroic figures who robbed from the rich and gave to the poor – a ‘gangster family’ along the lines of the Shelbys in the TV series Peaky Blinders would be a more accurate description.

Originally from the Picardy region in northern France, by the 12th century, the Folville’s owned a large estate in Leicestershire centred around Ashby Folville. Having supported the Barons’ rebellions of 1215 and 1263-65, the family had their lands temporarily seized by the crown, however, by the end of the century, Sir John Folville had regained their place amongst the most prominent families, not only within the county but nationally as well, due to having played a major role in Edward I’s military campaigns in Scotland. His rehabilitation confirmed by becoming MP for Rutland and Leicestershire from 1298 until 1306. According to George Farnham in an article written in 1913, the Folvilles were a family in turmoil after the murder of Eustice Folville (who had fought at the Battle of Evesham with Simon de Montfort, and been one of the defenders at Kenilworth Castle, see previous blog) in 1274. This set off an unsavoury scramble to gain ownership of the family estate amongst the various claimants, including John, the youngest son of Eustice (senior), who accused his own widowed mother, Juliana, and perhaps his older brother, Eustice, of orchestrating the murder of her husband. ⁵

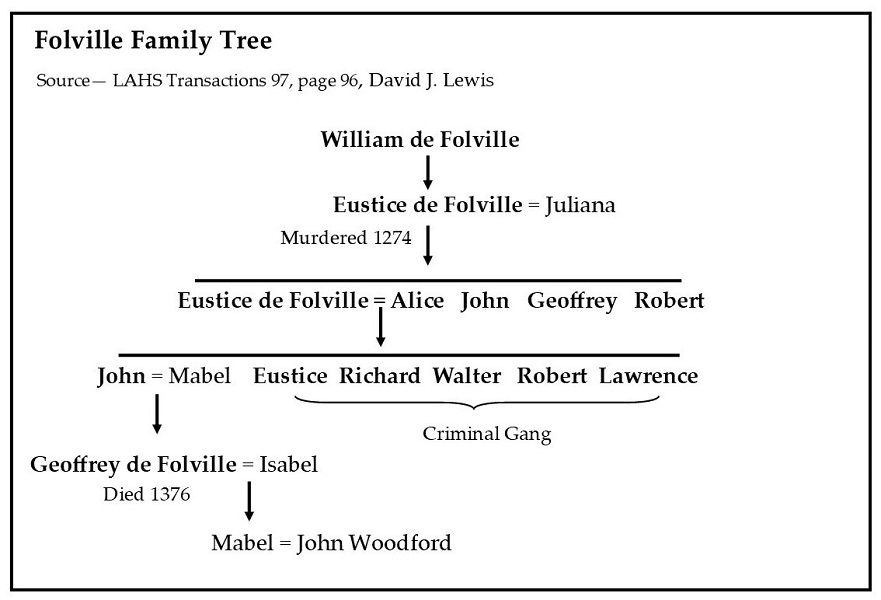

As the eldest son, Eustice (junior), was initially granted the estate in 1276, however, sometime during the same year, his younger brother, John, emerges as Lord of Ashby. It is out of this bitterly contested inheritance that the seeds were sown for the Folvilles’ future systematic law-breaking. In 1364, Geoffrey Folville was accused of robbery, the last recorded criminal act by the Folvilles. On Geoffrey’s death in 1376, the estate passes out of the Folville family (see family tree above). ⁶

This then was the backstory to how these ‘well-established pillars’ of the community became such notorious vagabonds and brigands. Two factors were crucial in their journey towards criminality. The breakdown in law and order following the famine, and the endemic corruption of those in power under the weak and arbitrary rule of Edward II, whose favourites were given carte blanche to use their positions for personal enrichment at the expense of those outside this privileged inner circle. Such was the level of bitter rivalry between those nobles supporting Edward and those opposed, that the resulting mayhem eventually led to a full-blown rebellion in 1321/2. After initial failures against the rebels, during which the king’s favourites, the Despensers (father and son both called Hugh), were forced into exile, Edward ultimately prevailed, with the insurgent leaders suffering swift and gruesome executions. The Despensers returned and an orgy of revenge against those who had rebelled was unleashed, with the Folvilles and la Zouches (another prominent Leicestershire landowning family) amongst the first victims.

It was at this point that the Folville brothers’ criminality began in earnest when they came under direct attack from the Despensers and one of their allies, Sir Roger de Beler, a recent neighbour after receiving lands around Kirby Bellars near Melton Mowbray for services to the king in 1318. Many of Leicestershire’s leading families were already at each other’s throats, some in support of the Despensers and others who were aligned to their main adversaries such as Sir William Trussell – who was said to have led a raid pillaging the Despenser's estate at Loughborough in May of 1322 – and the la Zouch family, both with extensive landholdings in the county.

Tensions between these antagonists reached such a fever pitch that a gang led by Eustice Folville ambushed and murdered Sir Roger de Beler near Rearsby as he travelled from Kirby Bellers to Leicester in 1326. Those involved included Eustace Folville and his brothers Robert, Walter, and Richard (Rector of Holy Trinity Church in Teigh, Rutland), plus Roger la Zouch and his brother Ralph, sons of Sir Roger la Zouch, Lord of Lubbesthorpe. The culprits had little choice but to flee to France.

It was in France that their fortunes would drastically improve. Coincidently, Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer were also in Paris at the same time, ostensibly arranging a peace treaty with the Queen’s brother, King Charles IV. But it appears that Isabella and Mortimer had other things on their minds apart from signing treaties, by this stage they had become lovers and were intent on overthrowing her husband and placing their son, Prince Edward, on the throne of England. King Edward had allowed his son to travel to France with Isabella so that the prince could offer fealty to the king of France for English controlled provinces, rather than having to go through the humiliating ceremony himself. This would prove to be Edward’s greatest ever mistake, having the heir to the throne with them in France was essential if Isabella and Mortimer’s intended rebellion was to have any chance of success.

The Folvilles, la Zouch brothers and Sir William Trussell (who had also escaped to France) joined Isabella and Mortimer’s invasion which landed on the coast in Suffolk on 24 September 1326. Such was the unpopularity of Edward and the Despensers that few were prepared fight for them, and they were promptly defeated. The Despensers were soon caught and executed, or perhaps more accurately ‘butchered’. Edward himself would have to wait awhile for his ‘grisly’ end. ⁷

Having been quickly pardoned by the new rulers, it was the turn of the Folvilles and la Zouches to now go on a rampage of vengeance. There followed a decade of almost officially sanctioned criminality which began with a series of robberies in Lincolnshire during 1327. Two years later, they even had the audacity to attack Leicester itself, robbing the Earl of Lancaster of livestock worth £l00 and the burgesses of goods and chattels to the value of £200 (£90,000 today). It was said that Eustace Folville alone was responsible for 3 to 4 murders between 1327-30. Eustace never faced justice for his crimes and if such an outcome was remotely threatened, he would have simply rejoined the king’s army and received a pardon. It appears that the Folvilles were also prepared to hire themselves out to commit crimes for others, for instance, in 1331 a canon and cellarer of one monastic house paid them a huge sum of £20 to destroy a rival monastic house’s watermill. Such was the extent of lawlessness during this period that priests and even abbots and bishops were often directly involved in criminal acts, an example of which was Richard Folville himself, the rector of the church in Teigh for over twenty years. Richard Folville was, in fact, the only gang member to suffer for his crimes when he was cornered in his own church by Sir Robert de Colville in 1340 or 1341. After a protracted siege in which at least one pursuer was killed, Folville was eventually dragged out of the church and beheaded in his own churchyard. ⁸

Despite being a priest, Rector Richard was one of the most criminally active of the Folvilles, being indicted for his part in the murder of de Beler and was believed to have led the kidnappers of Sir Richard Willoughby, Edward III’s Lord Chief Justice and one of the most corrupt members of the government (which was some achievement during this period) in 1332. Willoughby was apprehended near Grantham and was eventually ransomed for 1300 marks. Leicester chronicler, Henry Knighton, commented on this incident, describing the “savage, audacious” Richard as the leader (“socialem comitivam”) of this second most notorious of Folville offenses. Apparently, this was one of those occasions when this was a joint operation with the Coterel gang of outlaws. Three years later, they were in Nottinghamshire, where the Sheriff reported that “Robert and Simon de Folville, with a band of malefactors, were roaming abroad in search of victims to beat, wound, and hold to ransom.” ⁹

This stained-glass window was placed in Ashby Folville’s church by Eustace himself showing the gangs power and influence, as well as, although hardened criminals, their total immunity from any legal reckoning due to royal protection. Eustace received a full pardon from Edward III during the late 1330’s and was officially restored into the national establishment as if his criminal career had never happened. Though hardly a rare event during this period, it was relatively easy for the wealthy to purchase pardons from cash-strapped medieval monarchs.

Of course, the main victims of this cynical abuse of royal patronage and gang warfare between the ruling classes were ordinary people caught in the crossfire of these conflicts, and such was the chaos it is not surprising that acts of resistance, even by the likes of the Folvilles whose victims were often amongst the most corrupt in the land, would be seen as heroic and justified with at least some of the worst “false men” getting their comeuppance. It is, therefore, not surprising that Langland in his poem, Piers Ploughman, linked them favourably to Robin Hood.

Steve Marquis 2025. Email: stephen.marquis@ntlworld.com. This is the second blog exploring Leicestershire's Notorious Outlaws. The first one on exploring 13th Century Roger Godberd of Swannington is available here.

Notes and References

- Evan T. Jones (ed.), ‘Bristol Annal: Bristol Archives’

- Lawrence Stone, Interpersonal Violence in English Society 1300-1380, Past & Present, Volume 101, Issue 1, November 1983.

- W.G. Hoskins, Murder and Sudden Death in Medieval Wigston, LAHS Transactions, Vol. 21 (1939), pages 175-186.

- W.G. Hoskins, The deserted villages of Leicestershire, LAHS Transactions Vol. 22 (1946), pages 246-47.

- George Farnham and A. H. Thompson, The Manors of Allexton, Appleby and Ashby Folville, LAHS Transactions 11, 1913 page 70. Also, an article by David J. Lewis which translates documents related to the Folville family and estate from the 13th and 14th centuries, in LAHS Transactions Volume 97 (2023) page 96. Amongst the documents translated is the one which deals with Eustice Folville (the one murdered in 1274) receiving his pardon from King Henry for supporting Simon de Montfort’s rebellion – at a very expensive cost of course, pages 103/4.

- ibid, Farnham (1913) page 466 and 467.

- It has been a longstanding rumour that Edward was murdered by having a red-hot poker pushed into his anus through the centre of a bone horn, thus leaving no external marks. By supposedly choosing this particular method for his murder in the context of his alleged homosexuality, perhaps only increases suspicion concerning its authenticity.

- Some readers may be interested in following up on the most remarkable example of a corrupt leading churchman during this period. He was John of Tintern

who became the abbot of Malmesbury Abbey in 1340, although, his criminal activities began in 1318. It was as abbot that he progresses from a criminal into full-blown gangster. - Andy Gaunt, Medieval Outlaws: The Folville Gang, Mercian Archaeological Services CIC (2012), based on the: History of the Folvilles from: E. Stones, 1956, Leicestershire, and their associates in crime, 1326-1347. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society No. 7.

15th-century illustration, a gang of robbers murder a passerby. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Robbers_at_work#/media/File:Medieval_robbers.jpg