Sunday 13 October 2024

The Mysterious Archaeology of Saltby Heath: Part 2 The Excavations

LAHS Vice-President Robert Hartley provides a personal insight into this landmark Bronze Age site dig.

My own involvement with Saltby Heath began in August 1978, when I drove out from Leicester in a Land-Rover with a heavy trailer in tow. We were there to excavate a Bronze Age barrow and set up site cabins by the entrenchments in the adjacent field. We had a cabin for our wheelbarrows and mattocks, donkey-jackets and waterproofs, and another where we could make tea and store our sandwiches. We generally sat around outside for our breaks, and because it was the careless 1970s, we smoked a lot of cigarettes.

“We” were the Archaeology Unit of Leicestershire Museums, headed by Jean Mellor and Terry Pearce. Jean was a pioneering female archaeologist who had led a series of high-profile digs in Leicester, as the city was rather painfully dragged into the 1960s with the creation of the Vaughan Way and other new roads. In 1973 it had become part of the new Leicestershire County Council, and Terry in particular, with interests in Deserted Villages and in Aerial Archaeology, was pushing for excavations on rural sites. The Site Manager was a young graduate from Leicester, Patrick Clay, who would eventually go on to lead the University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) for many years. One of the youngest diggers was Richard Buckley. He was still at university and very much the “boy” of our group, but he already had a great interest in the subject. Having begun his active digging career at Saltby, he later shared the management of the team at ULAS and would of course go on to greater fame with the later discovery of King Richard III.

The Barrow Dig, 1978

We rented the old Keepers Cottage which was hidden down a track behind the trees on the prehistoric ditch named King Lud’s Entrenchments, and a pattern of life emerged. Monday morning departure from Humberstone Drive in Leicester, out along the Fosse Way to Six Hills and then along the Salt Way through the incredibly pretty villages of Eastwell, Waltham and Stonesby to Saltby, then on to the Heath.

For some reason I was elected to be the driver of the Land Rover, which gave me another privilege, for once work had started for the week, I would take Debbie Sawday into Grantham to shop for our food supplies for the week. Debbie, who came from a well-known Leicester dynasty, had been a pioneering drop-out in the early 1960s and later, working for Terry and Jean, had developed a specialism for studying and drawing pottery.

Another little job I got was establishing the “datum” for the site. The datum being a fixed point indicating the height above Mean Sea Level. To do this I and an assistant used a “dumpy level” and staff to take levels, beginning at the nearest OS Benchmark, on the county boundary, and following the edge of a plantation of larch trees on the parish boundary called Egypt Plantation, to the excavation site.

Once these preliminaries were sorted, we got down to the steady task of just digging, in all weathers. By the end of the dig, in December, we had accumulated an impressively large spoil bank overlooking the excavated area. At one point we put our scaffolding tower on it and got superb “aerial” photographs in the pre-drone age. Unfortunately, the wind then got up and blew the tower over, so we subsequently rebuilt it at a lower level.

Someone - I forget who, brought a cassette player, and at times we relaxed during our tea breaks to the evocative sounds of Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon.” Each evening during the week we headed out to a pub in one of the local villages, especially the Nags Head in Saltby, and the Tollemache in Buckminster, which had the additional attraction of a jukebox with Blue Oyster Cult’s “(Don’t Fear) the Reaper.” In contrast, our other favourite, the Crown at Sproxton, was a pub from an earlier era, with a single bar room with a hatch through which glasses of ale were served. The entertainment, as I remember it, was conversation and dominoes.

Patrick Clay subsequently published an excellent report on the barrow excavation, including the next season’s “dig” of a barrow at Piper Hole Farm, Eastwell. (Clay, P., 1981 Two multi-phase sites at Sproxton and Eaton, Leicestershire. Archaeological Report 2, Leicester Museums Art Galleries and Records Service. Museums Publication No 26.) Patrick went on to manage many projects, including the excavation of the medieval timber bridge at Hemington and the Hallaton Iron Age hoard. He completed a PhD on prehistoric settlement of the East Midlands which overhauled many previous ideas about the subject, but he looks back with most pleasure at the excavation and publication of the Saltby Heath barrow.

The barrow excavation involved the removal of the mound, with careful study of the layers and the finds. It was possible to study both the successive funeral activities, and also the buried soils which had been protected below the barrow.

The Barrow and its Burials

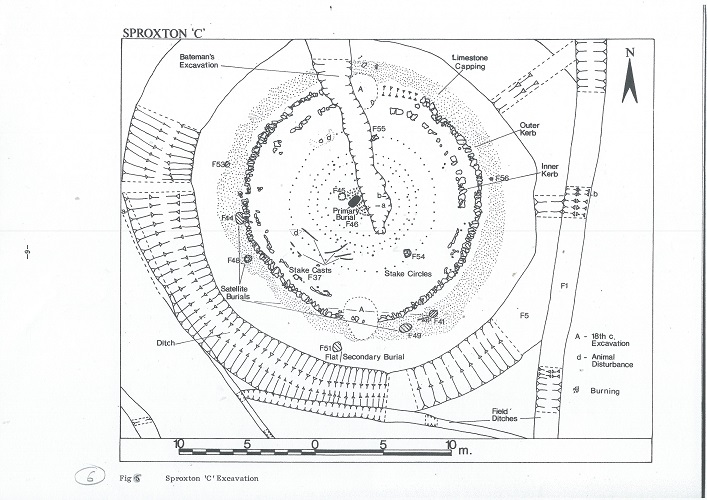

The creation of the barrow site began with the stripping of the turf, and the burning of a funeral pyre, with the body possibly placed on a wooden platform supported by four posts. The cremated bone was then placed in an oval pit (F46). Another small pit was dug nearby (F45) but contained no finds. The turf was brought back to make a low mound, and the area was defined by a circle of nine or ten wooden stake posts. Two more pits were dug outside the ring, and then four more concentric circles of stakes.

The site was then covered by a larger mound of soil, edged with large stones which formed a kerb. This material contained some early bronze age pottery. Perhaps to make this venerated location more obvious and notable, a trench was dug into the limestone all around the mound, and the stone was used to form a capping over the entire mound. This would have involved many days of work. It may have been prompted by two more deaths in the community, as two cremations were dug in areas sealed by the capping, and two more were dug into it. (F41,44,48,49).

Another cremation (F51) of a young woman, contained in an inverted collared urn, was placed in a pit which may already have been dug between the capping and the quarry ditch.

The burnt wood from F46 and F51 was subjected to new radiocarbon analysis, and the results published in 2018 (Trans Leics. Arch Soc, Vol 92). The revised dates for the pyres are: -F46; 1886-1688 BC. F51: 1965-1751 BC. The dates originally obtained in 1979 were respectively: - F46 1550 bc, and F51, 1490 bc (within 80 years or so). The remains are thus perhaps about two centuries earlier than we first thought.

Interestingly the “secondary burial” of the young female (F46) appears to be the earlier of the two. The authors of the paper note that these dates are firmly in the Early Bronze Age and seem to be linked culturally to burial practices in Wessex at that time, rather than to the traditions in Yorkshire. Genetic information gradually being gathered shows that these cremations are associated with a rapid replacement of the Neolithic people of Britain by migrants from the Continent who are associated with Beaker material. Far from being long-established residents, the people who carried out their extensive funeral ceremonies here may well have been relatively recent arrivals.

The Strange Story of the Collared Urns

The most impressive finds from the 1978 excavation were two fine pottery Collared Urns (from F48 and F51). They had both contained cremated female remains. F48 was placed upside down, protecting the remains rather than containing them. These were taken to Leicester and subsequently, when we refurbished the Jewry Wall Museum, they were put on display. The museum in those days had a complete wall of glass window looking across at the Roman Jewry Wall. At some date in the early 1990s some of the local youth discovered they could break the smaller panels and crawl into the museum without immediately setting off the alarms. They did this on two occasions, and on the second one they decided to steal something. Of all the items they might have taken, they chose the two Saltby Urns. As time went by, we resigned ourselves to the thought that we would never see them again.

About a year later, investigating another theft, the Police found some ancient pots, and contacted us. A cheerful bobby arrived one morning carrying the Saltby Urns by their collars, one in each hand. Amazingly they were still intact. Perhaps the spirits of the place were still looking after these remains.

The Earliest Evidence

Below the mound there was evidence of buried soils, suggesting that the area was originally cleared for farming at a date then estimated to be about 3200 bc, comparable with other dates in the East Midlands. Following clearance of the oak woodland the area was cultivated, but perhaps not for very long, before being found more suitable for grazing land. It subsequently seems to have been managed as grazing land more or less continually for some 4000 years, as the tides of history flowed around it. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the story of the Heath is this long period of use for livestock farming.

“Bateman’s Last Barrow”

My abilities as a “digger” were perhaps not noted for their subtlety, for I was, for several days, given the rather strenuous task of excavating the huge trench which had been dug out on September 21st 1860 by a gang of Victorian navvies under the direction of the celebrated “barrow digger” Thomas Bateman. Bateman is famous for excavating over a hundred barrows in his native Derbyshire. Each of his digs usually took a day, sometimes less, but despite this haste he must be given a lot of credit, for despite the fact that he died at the age of 39, he had already published reports on his activities and those of several of his contemporaries. In “Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire” and “Ten Years’ Diggings” he recorded evidence found in some 500 barrows in Derbyshire, Staffordshire and North Yorkshire. He carefully collected many artefacts from his digs and displayed them in a museum at his home in Middleton by Wirksworth. His finds have for many years formed the core of the remarkable archaeological collections at the Weston Park Museum in Sheffield. The most famous item is an Anglo-Saxon helmet with a boar for a crest, which was found at Benty Grange, Derbyshire and rivals the helmet of similar age from Sutton Hoo.

The last dig described in Bateman’s second book is well away from his home territory. At the invitation of the Reverend F Norman, he had come to Saltby Heath on September 21st, 1860, to open the two most prominent barrows here. In case you are wondering why, the Reverend Frederick was married to Lady Adeliza Norman, daughter of the Duke of Rutland, and clearly another of that eminent family to have an interest in archaeology. He opened the barrow near the Entrenchments and found what he later described as the bones of the man, “the hunter chief” deposited with “one of his dogs”, “high up in this considerable mound.” He noted, rather vaguely, that “Barrows of this class rarely repay the labour expended in opening them.”

He went on to the other barrow, cutting a large trench through it, but recording that “we were not so fortunate as to discover any interment in it.” His large trench was the one I later re-excavated. We discovered that he had missed the central cremation by just a few inches. He actually surmised in his book that this was probably the case, and that the cremations lay “in some part of the barrow not examined by us, owing to lack of time for more thorough excavation.

King Lud’s Entrenchments, and a Spitfire Pilot

King Lud’s Entrenchments form part of a series of ancient ditch and bank systems that are also found on the Heath. Shortly before we excavated the barrow, an amateur archaeologist carried out an unofficial dig on the Entrenchments. This was enterprising, but also illegal, as the site was a Scheduled Ancient Monument. To make the best of the situation, Patrick Clay had been called in to tidy up the cross-section and record it in as much detail as possible.

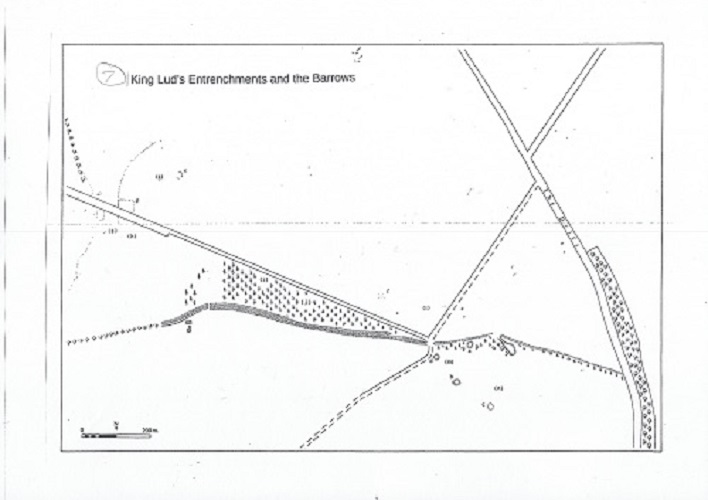

These activities prompted renewed interest in the earthwork - and a visit from the aerial archaeologist Jim Pickering. He had been recording cropmarks from the air for some twenty years and found evidence for many similar linear earthworks which have been levelled by later cultivation. The fragments of evidence extended from Northamptonshire to the Humber, but only in two places do these features survive as earthworks - at Stow Nine Churches near Daventry, and on Saltby Heath.

Jim had been a Spitfire pilot and flown biplanes in the defence of Malta. In later years he continued to fly both as a private pilot and also training young pilots in the Volunteer Reserve.

He became fascinated by the evidence of archaeology that he could see as crop marks in cereal fields each Summer. He would eventually contribute over 24,000 photographs to the National Monuments Record - quite possibly a record. His photos also inspired at least three episodes of “Time Team” - but his work is often overlooked. I have been doing my best to keep the memory alive by writing a series of articles for county journals - he carried out reconnaissance over some twelve counties, from the Severn Estuary to Flamborough Head, and from Rotherham to Peterborough. My latest have been a report on his work in Rutland for the Rutland Record (James Pickering and the search for cropmarks in Rutland, Rutland Record No.41 by Robert Hartley 2022) and an outline of his career for the forthcoming Leicestershire Historian.

Jim later won the British Archaeological Awards for his work on these Prehistoric boundary features, and King Lud’s Entrenchments played a part in allowing him to understand more about them. They are the best evidence we have for the original appearance of many miles of similar earthworks across Rutland and Lincolnshire.

A Survey of the Entrenchments

Some years after my time on the barrow dig, I returned to Saltby Heath as one of the team employed to survey Leicestershire’s archaeological sites. I arranged access in the depths of winter and was able to make a detailed survey of the earthworks. They still remain entirely mysterious to me - they are not in any obvious sense “defensive”, they stretch across the landscape in a reasonably direct fashion. They begin and end in what seems an arbitrary way. The east end of King Lud’s just seems to be intended to end at a very shallow valley which descends towards the north-east.

Why were they built? Presumably to define territories for some reason, but whether this was purely about ownership or involved some religious agenda is unknown. King Lud’s was later followed by the parish boundary between Croxton Kerrial and Saltby. The traditional name of the earthworks - the “Foulding Dykes” suggests some sort of use for managing livestock in an open landscape, but why go to such trouble rather than making fences?

Why have they survived here when they have been obliterated in so many other places? Presumably it is because Saltby Heath was for centuries grazed by sheep, so that the earthworks were not overgrown by trees until the last two centuries, but again it is something of a mystery that they should by so long have outlasted the similar earthworks around Oakham, Long Bennington, or Lincoln.

Looking Back

During our tea-breaks on the dig we sometimes got a bit philosophical. Excavating a burial mound, complete with human bones and ashes, does make one aware of one’s own mortality. We were disturbing the remains of people who had been placed here in sorrow and solemnity some 4000 years ago, and it seemed right that we should do this in a way that was respectful.

Writing in 1860, Thomas Bateman quoted some of the thoughts of Sir Thomas Browne, the 17th century antiquarian, who recognised as long ago as 1669 that buried layers of clay and soil could long outlast “strong and spacious buildings”. The remains of our barrow had survived the entire eras of Ancient Greece and Rome, of Christian Europe and even the British Empire. As he put it:

“Time, which antiquates antiquities, and hath an art to make dust of all things, hath yet spared these minor monuments.”

Robert F. Hartley (2024)

This blog is based on a lecture given by the author at the Crown Inn, Sproxton, Leicestershire on July 5th, 2024, 45 years on from the landmark Bronze Age burial site excavations on Saltby Heath.

Please see also Part 1, which focuses on the long history of human activity in this distinctive landscape.

Saltby Heath excavation with baulks still in place, Aug/Sept 1978. Photo by R.F. Hartley.