Sunday 6 October 2024

The Mysterious Archaeology of Saltby Heath: Part 1 The Heath

LAHS Vice-President Robert Hartley considers the long history of human activity in this distinctive landscape.

Why “Mysterious”? Surely Archaeology is a science, and we can now identify and date ancient sites with great accuracy, and increasingly understand the differences which identified and divided our predecessors. And yet we still cannot, and perhaps never will, understand the beliefs and ceremonies of people who lived before language was written down. We know quite a lot about the ancient sites on the Heath, but why they were built, and exactly how, and how they have survived, are still to some extent mysteries to us. In the Autumn of 1978, I was one of the team which excavated a Bronze Age barrow on the Heath, and having gone on to be one of the Survey Archaeologists for Leicestershire, I have often returned to the area and tried to understand more about it.

The Heath and the Three Ditches

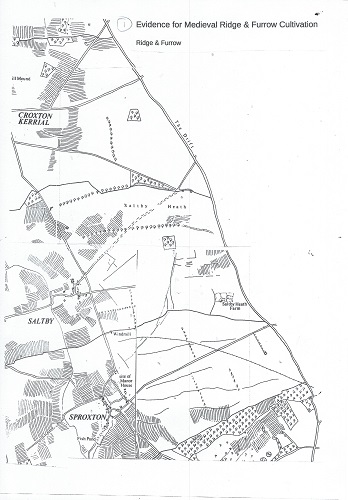

In most of Leicestershire, the era of Prehistory is hidden under the very widespread evidence of medieval farming systems and villages. Only in a few places does earlier evidence emerge faintly at the surface, and Saltby Heath is one of them.

The main reason was pointed out by John Nichols over 200 years ago when he quoted the opinion that “a great part of the Heath is of so shallow a soil and bad quality to admit of much cultivation.” which seems reasonable. He also included the Reverend Francis Peck’s observation that

“the sheep that feed on it often die mad of the wool-evil,” which seems rather dramatic...

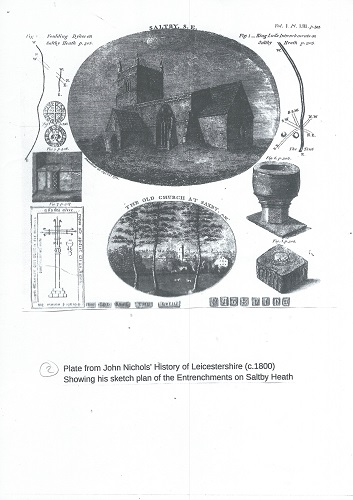

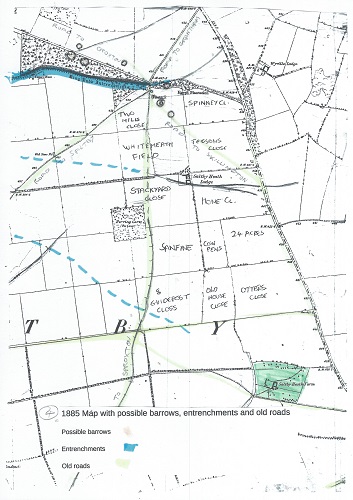

Some of the Prehistoric burial mounds on the heath were clearly well visible in the 18th and 19th centuries, and in fact the largest of them was the object of one of the first archaeological digs in Leicestershire, when it was opened up in about 1680 by John, the First Duke of Rutland, who apparently found it to be “full of bones”. Also visible were the ancient ditch and bank systems. In 1160, when Croxton Abbey Church was still being built by the stonemasons, the institution was endowed with lands in Saltby at “ad Tres Fossatas”, or the at three ditches or dykes.

John Nichols published a sketch plan of the location of the three ditches in 1795, in his magnificent series of volumes on “The History of the County of Leicester”, but by the 1880s only the northern entrenchment remained to be seen. Despite being planted with trees, it is still deep enough to fall into, or more accurately, roll into, today, but it is difficult to see, especially in the Summer when the vegetation grows over it. It was the most impressive of the three ditches, for someone gave it a name, and since at least the 18th century it has been known as “King Lud’s Entrenchments”.

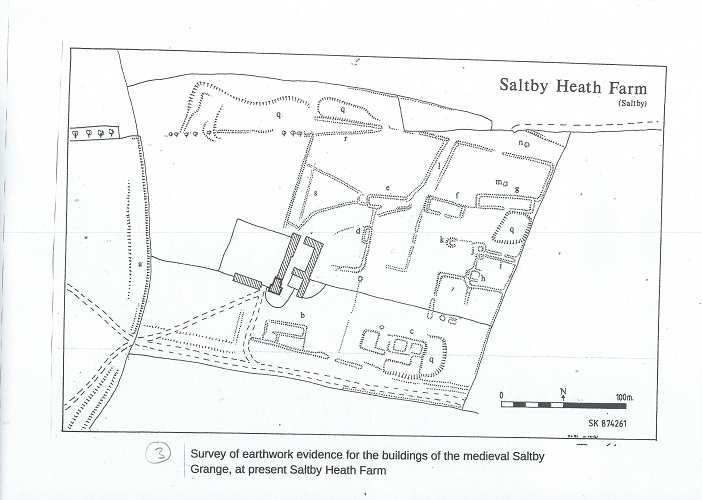

Croxton Abbey presumably used the Heath for pasturing sheep, an activity which became increasingly profitable through the 14th and 15th centuries. They constructed a spacious stone-built Grange Farm as the base for their operations here. (There is a possible alternative story: Paul Courtney in his thesis on Leicestershire grange farms notes that the Abbey of Vaudey in Lincolnshire (the site is in the present Grimsthorpe Park near Bourne) possessed a grange farm at Saltby by 1227, and he identifies this with Saltby Heath Farm (Courtney 1977 Cardiff University, 24–5)

Nichols records that ‘Saltby Grange ... abuts on the ancient great Drift Road to London ... now nearly in disuse ... Foundations of buildings apparently have covered four or five acres of land. Many have been dug; other yet remain and great quantities of ashes and cinders, particularly in one place, where tradition says was a forge, have been ploughed up.’

‘A well, cut out of the solid rock, 32 yards deep, of a bell-like form at the bottom, was discovered here some years ago; near the surface were leaden horizontal pipes, to convey water to different parts of the buildings. These were traced, but the cisterns had been removed. The water is excellent ...’ (Nichols 1795, 305).

In 1541 the possessions of the recently-suppressed Abbey were given by the Crown to Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland, but life for the local villagers no doubt continued much as before.

By the early 18th century the open Heath was being used for training and exercising horses. “Here was any length of turf for the hard and the tender-footed horse: in wet weather on The Heath, in dry on The Moor. It became “famous for horse-races.” Stables were built and there was a three-day festival of racing each year, with a prize plate worth £50 given by the Duke of Rutland, and another of the same value, named “The Whimsical Plate” raised by subscription. There were also matches every Monday fortnight in the summer. The presence of this informal economic activity may well have attracted Romany travellers, as many horse-festivals still do to this day.

This might explain the name of Egypt Plantation, which is a plantation of larch trees on the parish boundary just north of where we excavated. This could have been a traditional “atchin tan” or stopping place of the Egyptians or as they were more commonly known, Gypsies. The old green lane named Sewstern Drift, which forms the county boundary for miles in this area, was a good road for travelling slowly, and often used to move cattle and sheep up and down the country. A mile to the north the Drift is crossed, at a place called “Three Queens” by the Salt Way on its route between Barrow on Soar and the fenland saltings, so we are near the junction of two ancient cross-country routes which the Gypsies no doubt followed on their journeys around the country.

Sadly, all of this Olde English merriment did not necessarily increase the sum of human happiness, for Nichols notes disapprovingly that “the inhabitants” ... “neglected their business and became gamblers and the companions of grooms.” The existence of the open heath was ended by enclosure in 1791, after which it was divided up into fields, and increasing areas of it were ploughed to grow cereal crops.

After Enclosure

The Heath was divided into rectangular fields, although it seems that many of them continued to be grazing land. Long narrow plantations of larch were set along King Lud’s and many of the other field boundaries. Over time they grew to seem like enormously tall hedges, giving the Heath an air of Brobdingnag, which it still retains in places. Presumably, the larches acted as windbreaks, perhaps preventing the thin soil from being blown away by gales. Saltby Heath Farm was redeveloped, with another farm built on a new site further north.

Nichols recorded five roads across the Heath, meeting at the east end of the Entrenchments. Two of them - the direct roads to Sproxton and towards Skillington, ceased to exist, and the road to Croxton seems to have been diverted to follow the north side of the Entrenchments. Only the road from Saltby and its continuation towards Grantham still seem to follow the original alignments.

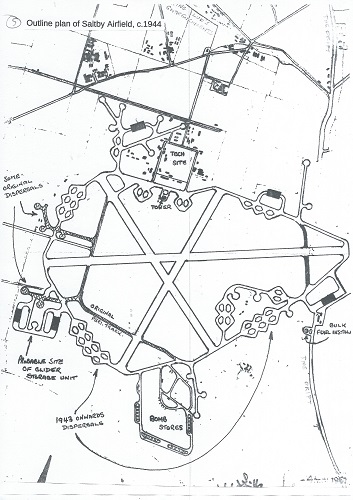

The Airfield

A big change to the area took place in 1941, when Saltby airfield was constructed, initially with grass runways. Remarkably a Luftwaffe photograph survived the war and can be seen on the airfield’s Wikipedia page. During 1943/4 it was reconstructed with concrete runways and hard standings. Many more, and more permanent, buildings were built. A couple of these decaying brick and concrete structures survived near our dig site. To us in 1978 they seemed to be from an age nearly as remote as that of the barrow. They played a part in world history in early June 1944, when large numbers of US Army divisions converged on the airfield and were flown out in aeroplanes and towed gliders to be dropped on the coast of Normandy as part of the “D-Day” invasion. I remember hearing an eye-witness account of these events from a Saltby resident who was a child at the time. Since the war, the airfield buildings have gradually been removed. I think when we were here in 1978 parts of the runways were still being broken up for hardcore. The Buckminster Gliding Club set up home here and uses the remaining runways.

Another, now largely unnoticed change, was the excavation of iron ore from a wide area around the southern edges of the heath, mainly in Sproxton parish. In the 1950s and early 1960s trainloads of ore were taken away along what was known as the High Dyke Branch to the East Coast Main Line to go on to Scunthorpe Steelworks.

Meanwhile the demands of modern farming had brought virtually all the old Heath into arable cultivation, rapidly removing any remaining trace of the old earthworks, which is why we came to study the southern barrow, by this time in a ploughed field and being quite rapidly reduced in height.

R.F. Hartley (2024)

This blog is based on part of a lecture given by the author at the Crown Inn, Sproxton, Leicestershire on July 5th, 2024, 45 years on from the landmark Bronze Age burial site excavations on Saltby Heath.

Please see also Part 2, which focuses on the 1978 excavations.

The excavated Saltby Heath barrow on a suitably misty morning, November 1978. Egypt Plantation on the left, the Lincolnshire border along Sewstern Lane in the distance. Photo by R.F. Hartley.