Sunday 16 February 2025

The Melton Mowbray Polish Resettlement Camp: Differing Perspectives

LAHS Member, Jakub Milcarz, explores the contrasting views of the British government and Polish inhabitants of the camp during the 1950s.

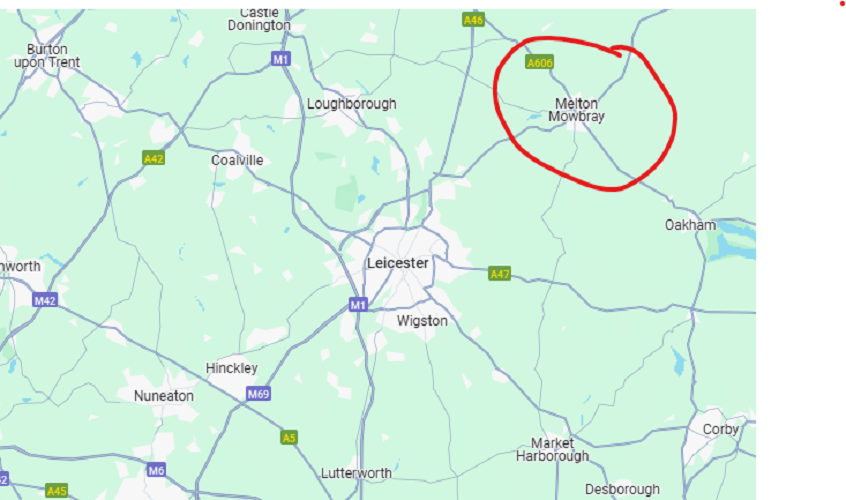

In a previous blog I have presented an overview of the topic of the Polish Resettlement Camps in the United Kingdom; an often-overlooked aspect of Britain’s migration history, even amongst historians of the Polish diaspora. The previous blog post explored the story of how the Poles ended up in Britain, and what the Polish Resettlement Camps were. This blog post will aim to zoom in on one camp, that of Melton Mowbray, and use it as a case study of how the camps were perceived in the early years. As the camp no longer stands, primary sources remain our only window into this place, which existed between 1947 and 1960. The two perspectives through which this blog post will explore the conditions in the camp are those of the government, represented in a report of camp conditions, conducted on the 8th of February 1951, and of a camp inhabitant, based on her own recollections, written for a blog commemorating the memories of the Polish diaspora world-wide. As will become evident, whilst the reports agree on the dire conditions in the camps, the tone of the two documents can shed light on how the Poles were perceived in the official view of government administration, and how the Poles saw themselves during these formative years of the Polish diaspora.

An Introduction to the Camp

Like most of the Polish Resettlement Camps, the camp in Melton Mowbray began its existence as a military site, specifically a RAF base. In their book Polish Resettlement camps in England and Wales 1946-1960, Zosia and Jurek Biegus explained that ‘In 1947 there were 350 Polish airmen, officers and a small contingent of British officers still on site, operating as an RAF station’. The government report tells us that the population was 838 in 1951 whilst Zosia and Jurek Biegus quote a 1955 report from the committee for the education of the Poles which puts the number of residents as 572. As such the population fluctuated throughout the period as people moved in and out (due to reasons like employment, study, or emigration to another country) but according to the Biegus,’ ‘never exceeded 1,000’.

The book by Jurek and Zosia Biegus is an important part of the historiography of the camps as it is the only book dedicated to the Polish camps as a whole. Although the authors were not professional historians, and the methodology of the book is simply interviewing people who lived in specific camps (e.g. only 3 people were interviewed for the Melton camp and the entire section on it lasts only 9 pages, including photographs) the book is a monumental overview of each camp, and one of the few sources on this topic.

According to the authors, ‘The camp consisted of several sites scattered over small hills with distances of up to three miles from one another.’ The book also tells us that this camp was considered ‘better’ then many of the other camps, and this was why it was chosen as being one of the family camps, with one site ‘allocated for use by Polish dependants arriving from Displaced Persons (D.P.) camps in Africa’. As in most of the Polish camps, Nissen huts were the dominant form of housing, often occupied by multiple families (especially in the early years), as well as housing communal activities such as the Church. In essence, this camp was a RAF base converted to a settlement for reuniting families, uprooted and scattered throughout the world by the Second World War. This is crucial to understanding the Melton Mowbray camp; it was a camp for Polish soldiers and their families who arrived in this country with nothing, were placed into a camp recently abandoned by soldiers and had to make do with this.

The camp was mainly run by the Poles themselves, through a mixture of paid staff and volunteers as part of the larger Polish Resettlement Corps. Although subordinate to the Assistance Board with a Warden present, overall, the camps were mostly autonomous.

A Note on the Sources

The government report on conditions in the camp is part of a larger collection of reports held at the National Archives. The aim seems to have been to create a survey of living conditions in all the major camps in which the Poles lived. It is a document produced to give a brief overview of life in the camps to those, who in theory, were responsible for conditions there, namely the Assistance Board. The document was therefore intended as a survey, a panorama of camp life, and was to be seen as being ‘objective.’ Naturally, no source is ever objective and as will become evident certain value judgements of the reporters are demonstrated.

The memories of Urszula Szulakowska, the Pole from the Melton Mowbray camp, created for a website commemorating the Polish diaspora, makes no pretence of objectivity, and instead offers a deeply personal recollection of camp life. They focus not just on the living conditions themselves, but also on the emotive aspect of camp life and identity. It is not surprising therefore, that both sources tend to highlight the role of their ‘side’ in the positive aspects of camp life and blame the other for the negative.

Historians have not researched the topic extensively, and sources relating to the camp are not easy to come by. The timing of the government report is well placed in the chronology of camp life. The camp began being used by Polish Displaced Persons in 1946. It was finally closed around 1960. Being written in 1951, the report gives us an idea of what the camp looked like during the first few years, but not right at the beginning, when it was still being set up, or towards the end of its existence, by which point the population had severely decreased as more Poles managed to find ways of settling outside of the camps.

As for the source by Szulakowska, whilst there are a few testimonies from the Melton camp available online, this one seems to me to be the most detailed. Whilst Szulakowska was only in the camp towards the end of its existence, this serves as an interesting comparison to the government source as it shows us how some of the themes touched upon, covered the whole period of the camp’s existence. Furthermore, Szulakowska went on to become a historian, even publishing an academic book about a different camp (The Sulby camp near Husbands Bosworth). Her perspective is therefore rather unique, and in my opinion, Szulakowska often spoke on behalf of the diaspora, thus in some ways is a fitting counter example to the inspectors of the Assistance Board, serving as a mirror, investigating the authorities of the camps as much as they investigated the inhabitants.

The Government's Report

What comes out the most strongly in this report is that it was rather comprehensive, showing a genuine effort on the government’s behalf to understand conditions on the ground. It focused on such aspects as energy, common services, healthcare, toilets and even education. The report stated that in 1951 there were 838 residents (331 men, 377 women and 130 children), that all ‘capable residents were in employment’, that ‘the doctor is quite satisfied with the general standard of health’ and lists many such interesting statistics which are rather enlightening on basic facts of camp life.

The report also demonstrated the government’s concern for the camp and showed the officers conducting the report standing up for the camp’s interests. For example, pointing out that local traders had damaged ‘the pathway and land’ with their vehicles, as well as that a letter had been sent to the culprits instructing them to stick to ‘recognised roads.’ It also highlighted a need ‘for subsidiary roads,’ and that the estates manager was requested to ‘make a survey and report his recommendations to headquarters.’ This shows that the officers conducting the report were active in identifying room for improvements in the camp.

The report however also listed shortcomings, which shed light on areas of conflict between the camp administrators and the camp inhabitants. For example, it lamented at the fact that whilst individual fuses in each hut have been ‘sealed’- ‘the majority of seals have been broken.’ Furthermore, ‘the estate manager was directed to approach the Ministry of Works, to have all fuse-boxes re-sealed and adequate inspections maintained.’ This shows that the government did not welcome the Poles meddling in the structures in which they were supposed to live. The report was also concerned about ‘unauthorised structures’ and pointed out that ‘Approximately 70% of the householders have erected shelters, hen coops etc.’, noting that these structures ‘generally serve the purpose for which they are intended but are untidy and badly constructed’. This is very enlightening. The government looked with suspicion at the Poles’ efforts to make themselves more at home, and wanted to ensure that the structures were used solely for the purposes they were built for, and were critical of any deviation from this.

Overall, the government report shows us that the government was concerned about the Poles’ autonomy, and did not welcome their initiative to improve camp conditions. The camps were not supposed to be homely or even welcoming. They were supposed to be orderly. The Poles in this report come across as quite mischievous, needing to be supervised as well as managed. Needless to say, the Pole’s saw things quite differently.

The Polish Perspective

Urszula Szulakowska’s account of life in the Polish camp is of course different. As well as referring to a later period (1957-58) the account is retrospective, looking back at a childhood in this camp. Szulakowska’s account is much more bitter towards the government, for example, Szulakowska argued that ‘It should be pointed out that although the Poles lived in drafty, damp barracks without running water, or heating and had to use communal sanitary arrangements, they were, nonetheless, expected to pay rent for these barely adequate facilities’. Szulakowska further added that ‘They also had to pay for their own electricity. In addition, they paid taxes and national insurance just like the British population.’ From the get-go Szulakowska explained that despite the poor conditions that the Poles experienced, they were not freeloaders but quite the opposite. They themselves paid for the rough accommodations that they found themselves in.

Szulakowska previously lived at the Polish camp in Sulby and argued that her ‘Nissen hut in Melton was in a far worse condition than the one at Sulby.’ Despite this, Szulakowska pointed out that ‘All the Polish homes were clean and shiny, despite the awful poverty’ and that many Poles even at that point made their own furniture. Here we have a different perspective. The camp was supported by Polish money and labour, and 6 years after the government’s report, there was still ‘great poverty’.

Conclusion

Taken together these sources present a very interesting picture of life in the camp. They show tensions between the camp authorities, and the spontaneity of the inhabitants. The authorities were concerned with order, and looked on with suspicion at the Poles who attempted make their lives in the camp better. On the other hand, the Poles, clearly full of contempt at the government’s instructions, continued to organise their resources in a creative and constructive way. It is interesting to see the tension that exists when the views of administrators clash with the views of the people who are affected by their decisions. In the aforementioned book on the camps, the authors tell us that initially the government even tried to keep the men and women segregated in accordance with the ‘King’s Regulations’ however quite soon the military discovered how difficult it was to marshal civilians, especially mothers and children, in the same way as troops, so the mothers and children won. This is of course just an introductory overview of this topic, but one which is necessary to understand the early years of life in the Polish Resettlement Camps.

The author of this article, Jakub Milcarz, was the 2024 LAHS BA History prize winner for his dissertation ‘Living Conditions in Polish Resettlement Camps 1947-1960’ (De Montfort University, 2023)

Bibliography

All images came from the Polish Resettlement Camps in the UK 1946-1969 website. A site created by Zosia and Jurek Biegus, authors of the 2013 book Polish Resettlement Camps in England and Wales which documents life in 30 camps after WW2.

Bailkin, Jordanna. Unsettled: Refugee Camps and the Making of Multicultural Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Burell, Kathy.” Homeland memories and the Polish community in Leicester. In” The Poles in Britain 1940-2000, From Betrayal to Assimilation, edited by Peter D Stachura. London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2004.

Biegus, Zosia and Biegus Jurek, Polish Resettlement Camps in England and Wales 1946-1969. Essex: PB Software, 2013.

Davies, Norman. God’s Playground: A History of Poland Volume II 1975: to the present. New York: Columbia University Press 1981.

Lanes, Thomas. Victims of Stalin and Hitler: The Exodus of Poles and Balts to Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2004.

Milcarz, Jakub, ' Polish Resettlement Camps in Leicestershire', Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society Blog, 2nd June 2024.

Nocon, Andrew.” A Reluctant Welcome? Poles in Britain in the 1940’s.” Oral History. 24 (1996) 79-87.

Paterson, Sheila.” The Polish Community in Britain,” The Polish Review. 6 (1961): 69-97

Rennie, Nick, 'New Melton housing scheme to include Polish Nissen hut heritage centre,' Melton Times, 3rd November 2022.

Rogalski, Wieslaw. The Polish Resettlement Corps 1946-1949: Britain ‘s Polish Forces. Warwick: Helion & Company Ltd, 2019.

Stachura, Peter, D.” The Poles in Scotland 1940-1950. Some New Perspectives.” in European Immigrants in Britain 1933-1950 edited by Johanes Dieter Steinert and Inge Weber-Newth 171-199. Berlin: K.G Saur, 2003.

Szulakowska, Urszula. Husbands Bosworth Polish Resettlement Camp (1948-58): Polish Identity in Post-War Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2020.

Urszula Szulakowska, ‘Life at Melton Mowbray Polish Refugee Camp, 1957-58’

A Polish family outside their Nissen Hut in Melton Mowbray 1954.. Photo courtesy of Polish Resettlement Camps in the UK 1946-1969 website. https://www.polishresettlementcampsintheuk.co.uk/