Sunday 4 May 2025

The Indian-inspired ‘Islamesque’ in Rutland

LAHS Member Bob Trubshaw explores influences on Romanesque architecture, in the ‘foliage-sprouting faces’ of Tickencote and Stoke Dry.

In an earlier LAHS blog, Patrick Clay revealed Roman Leicester’s links to military legions and the wider Roman Empire, such as Egypt. In this article, I will show that North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean were also key to developments in Britain and Europe around the twelfth century. Curiously, these 'developments' are also named after the Romans. I'm referring to the style of architecture known as the 'Romanesque' because it is considered to emulate Roman methods of construction.

The Romanesque first developed in the tenth century in northern Italy, then spread into Catalonia and southern France. However Romanesque architecture changes after appearing in Sicily shortly after 1091. This is when the Normans finally won control of the island from Muslim caliphs. The Emirate of Sicily (827 to 1091) was a milieu where Muslims, Jews and Christians traded. Luxury goods from North Africa made their way into Europe. As a result, Palermo, the capital of Sicily, was at the time, one of the largest and wealthiest cities in Europe.

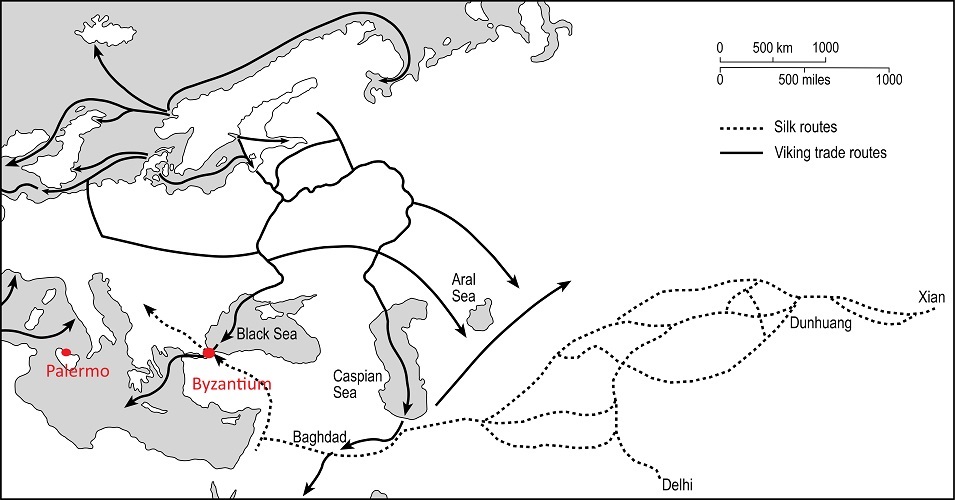

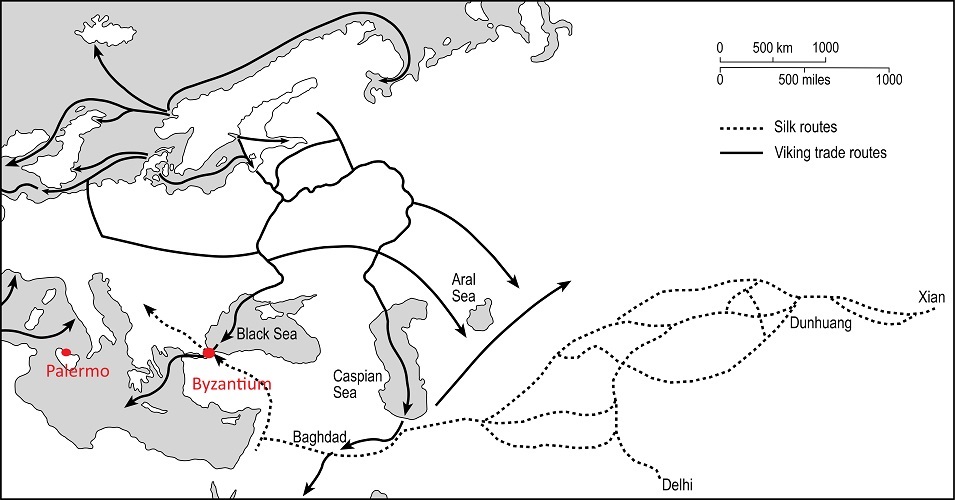

Europe imported a wide range of luxury items from the eastern Mediterranean – with many of the items originating much further east, along the so-called 'Silk Roads' into western China. What was Europe selling to pay for these luxury items? What records there are suggest wool, hunting dogs, even some horses. But by far the greatest export was slaves. According to the meticulous research of the historian Michael McCormick, each year from around the fifth to eleventh centuries, many hundreds of British people were taken by boat across the English Channel, sold at places such as Dorestad (an early medieval emporium, located in the present-day province of Utrecht in the Netherlands), and then walked the length of the Rhine, dragging a cargo vessel against the current using a rope. These slaves then walked over the Alps to end up near what is now Venice where they were sold to buyers in the Levant (McCormick 2001: 237–69). Ireland was a major source of these slaves, with Dublin being the place of embarkation. In Europe, Prague was the leading slave-trading city; indeed 'Slav' is cognate with 'slave'.

Without the insatiable demand for slaves in the Islamic countries around the Mediterranean then northern Europe and the British Isles would not have had the wealth to build Romanesque churches and castles, or for the nobility to buy luxury items offered by the merchants in Byzantium and Palermo.

The main reason this lucrative slave trading died out around the end of the eleventh century was because eastern Europe converted to Christianity. The understood 'rules' were that any pagans or infidels could be captured and enslaved. But Christians were not allowed to enslave Christians, just as Muslims were not allowed to enslave Muslims. However, this arrangement was undermined by Jewish slave traders who supplied Muslim slaves to the Christian world and Christian slaves to the Muslim world, as well as pagan slaves to both.

The Normans in Sicily celebrated their victory over the Emirate in 1091 with numerous 'prestige construction projects', mostly castles, churches, and summer residences. These were all designed and decorated to look like secular and religious buildings in North Africa – a style known as Fatimid-Zirid. Between 909 to 1171, the Arab Fatimid Caliphate was a significant power in the Mediterranean region, controlling parts of north Africa, Sicily, and the Levant. The Berber Zirid Dynasty ruled what is now Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia from 972 to 1148 (although they lost control of the central Magheb in 1014).

There can be little doubt that the exceptionally skilled craftsmen who built and decorated the Romanesque buildings on Sicily for the new Norman lords were neither Sicilian nor Norman. They must have been North African. Whether they came to Sicily because of the prospect of well-paid work or had been captured and enslaved is an open question. But even as slaves they would have been well-looked after as their skills were highly regarded. They were referred to at the time – and for a good many centuries later – as 'Saracens'.

The style of decoration and construction adopted in Sicily at the end of the eleventh century quickly spread to Italy, parts of Switzerland, Andalusia and then the rest of Iberia, and subsequently to what is now France and Germany, eventually reaching the British Isles. As noted, art historians call it 'Romanesque'. But from the end of the eleventh century in a great many details, both of construction and decoration, Romanesque buildings look the same as Fatimid-Zirid architecture in North Africa, created by Muslim craftsmen.

In a recent book called Islamesque: The forgotten craftsmen who built Europe's medieval monuments, the arabist scholar Diana Darke argues in convincing detail that seemingly all 'Romanesque' cathedrals, churches, castles and hunting lodges built between about 1100 and 1250 must have employed Muslim master craftsmen, probably trained in North Africa or the sons of such 'Saracens' who had settled in Europe. There must have been a considerable number of these 'Saracen' artisans living and working throughout Europe otherwise the Romanesque buildings would never have been built and decorated to such an exceptionally high standard. (Darke specifically argues that Muslim craftsmen were only associated with Romanesque buildings after 1091. However, some of her 'diagnostic' evidence is also conspicuous on earlier Romanesque buildings in northern Italy. Therefore 'Saracens' might have been associated with all phases of the Romanesque.)

The possibility of Mediterranean craftsmen working in Europe and Britain should not surprise us because, in the centuries before the Romanesque style decoration was adopted, ecclesiastical sculptures were carved in the 'Byzantine style'. There are several excellent examples from the ninth and tenth centuries in the church at Breedon on the Hill. In principle these could have been carved by English masons inspired by motifs on more portable items originating in eastern Mediterranean, such as small carvings, decorated textiles and manuscripts, and decorative metalwork. But if such goods – and the ideas incorporated into them – could travel from the eastern Mediterranean to Leicestershire then so could the craftsmen too.

Darke discusses numerous examples of twelfth century churches in Britain which closely mimic Islamic buildings of the time. But she misses out three excellent examples of early Romanesque decoration in Rutland. All three tell us that the 'Romanesque' doesn't stop in North Africa or Byzantium. Instead, it stretches across north India.

In her book Explore Green Men, Mercia MacDermott (MacDermott 2006) looked at the oldest examples of Romanesque sculpture to survive in England – such as the south doorway of the church in Kilpeck, Herefordshire.

_A.jpg)

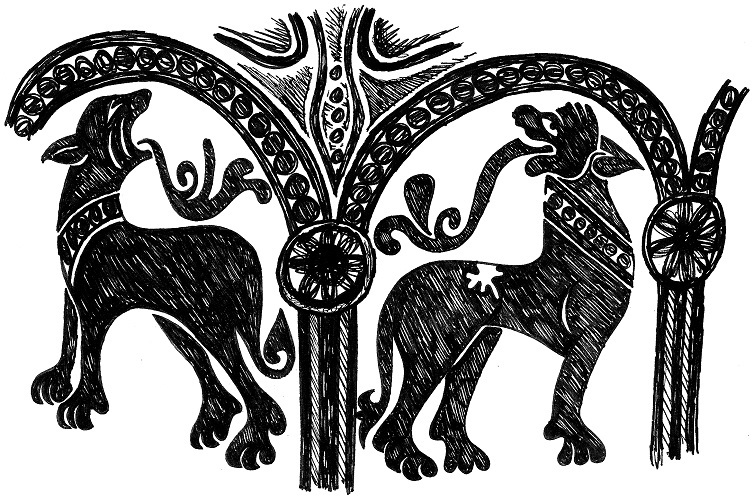

She spotted that the foliage-sprouting animal on the left-hand capital was the spitting image of a mythical Indian animal known as a makara. Right down to the row of 'dots' (strictly 'pearls') forming a central band of ornamentation. The foliage-sprouting human face on the right-hand capital at Kilpeck has two fronds of vegetation, also with the rows of 'pearls', so is inspired by Indian art although not necessarily an exact copy.

There are a number of other early Romanesque carvings which closely match the Kilpeck capital, including a tympanum at Wenlock Priory in Shropshire.

In the East Midlands there are examples of foliage-sprouting heads with rows of 'pearls' in Rutland, two at Tickencote and one at Stoke Dry.

Tickencote is a remarkable example of Romanesque architecture as the vaulted chancel is one of the oldest to survive, having been built between 1130 and 1170. Also remarkable is the complex chancel arch, probably erected between 1130 and 1150.

This was originally semi-circular but has distorted out of shape over the centuries. Among the many different faces are two sprouting foliage. As with Indian makara there is only one frond of foliage, with a row of 'pearls' forming part of the decoration.

At Stoke Dry two early twelfth century Romanesque columns survive as part of the chancel arch.

They have complex decoration which includes a foliage-sprouting quadruped. Like Indian foliage-sprouting animals there is only one 'frond' of foliage.

More symmetrical double foliage-sprouters take on a life of their own in the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, becoming a frequent motif on corbels, capitals, and roof bosses.

Whoever carved these early Romanesque foliage-sprouters was familiar with Indian art – whether small portable sculptures, decorated textiles or manuscripts, or metalwork. Whether they knew they were from India is debatable as they would have been transported along the Silk Roads and traded in places such as Byzantium, by then known as Constantinople. As Constantinople was the centre of the Eastern Orthodox church from the fourth to eleventh centuries then anything seemingly from there would be regarded as a good option for decorating churches (the rift between Eastern Orthodox Church in Constantinople and the Catholic Church in Rome started around 597 but there was no full separation until 1054).

Diana Darke's recently published research suggests that Romanesque churches were built by craftsmen from North Africa. In which case they may well have encountered decorative artefacts from India which had been traded at Palermo on Sicily. Cat Jarman's 2021 book River Kings looks at how the Vikings traded from Scandinavia to the western end of the Silk Roads. These trade routes would still have been functioning a century or so later when the Normans (themselves of Scandinavian origin) were using Sicily as a trading base.

The early medieval trade routes which connected the British Isles, Scandinavia, the whole of Europe with places to the east along the Silk Routes as far as northern India and western China. However European people would think the goods were from Constantinople as that's where they had been traded. In essence, Europeans bought from 'middlemen' in Mediterranean ports and not from the traders travelling along the Silk Roads. Presumably, there were a great many 'middlemen' strung out every few hundred miles along the different sections of the Silk Roads, each time masking the actual origin of the goods.

Mercia MacDermott initially identified foliage-sprouting animals in Indian art contemporary with the early Romanesque. However soon after the first edition of her book was published a group of researchers showed that the so-called 'three rabbits' (or 'three hares') motif can be seen on a roof boss in one of the Mogao Caves (also known as the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas), a UNESCO World Heritage Site near Dunhuang in the Gobi Desert, north-western China. The Mogao Caves were created between AD 589 to 618, although the roof boss may be more recent. Nevertheless, it is a good example of how motifs can travel significant distances. The same 'three rabbits' motif has survived on a medieval Iranian metal tray and on roof bosses in various English churches carved around the fourteenth century. In the second edition of Explore Green Men, Mercia included an outline of the 'three rabbits' motif's migration as it provides a slightly more recent parallel to her insights into the Indian foliage-sprouting animals and faces.

.jpg)

I am not aware of any medieval examples of the 'three rabbits' in Leicestershire or Rutland. But the three foliage-sprouters at Tickencote and Stoke Dry were inspired by art which had once been produced in India, then made a long journey via Constantinople and/or Palermo before being brought to Britain by 'Saracen' craftsmen recruited from north Africa because of their exceptional skills.

Bob Trubshaw 2025. bobtrubs@indigogroup.co.uk

Selected sources

Darke, Diana, 2024, Islamesque: The forgotten craftsmen who built Europe's medieval monuments, Hurst.

Fontaine, Janel M., 2025, Slave trading in the Early Middle Ages: Long-distance connections in northern and east central Europe, Manchester UP.

Frankopan, Peter, 2015, The Silk Roads, Bloomsbury.

Jarman, Cat, 2021, River Kings: A new history of the Vikings from Scandinavia to the Silk Roads, William Collins.

McCormick, Michael, 2001, Origins of the European Economy: Communication and commerce AD 300–900, Cambridge UP

MacDermott, Mercia, 2006, Explore Green Men, 2nd edition, Explore Books; available as a free PDF

Wikipedia Entry - Prague Slave Trade

Wikipedia Entry - Slavery in Ireland

Background image: Tickencote church vaulted chancel. Photo by Bob Trubshaw c.2015.

Tickencote church vaulted chancel. Photo by Bob Trubshaw c.2015.