Sunday 19 January 2025

Roman Lead Sealings Found in Leicester and What They Can Tell Us

LAHS Vice-President Patrick Clay, explores some of Roman Leicester’s links to military legions and the wider Roman Empire.

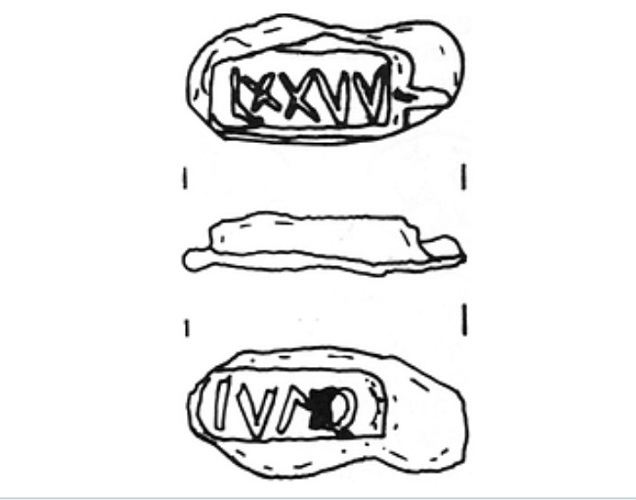

Archaeologists are often asked what was the favourite object they have found during their work. A variation of this happened to me in August 1976 when Ian Glen, one of the Sunday volunteers we were working with, asked what object would l most like to find. At this time, Leicestershire Archaeological Unit, part of Leicestershire Museums, was working on a Roman site, outside the defences of Roman Leicester, on Great Holme Street, (where Narborough Road North is now). It had revealed evidence of industrial activity including pottery kilns, rubbish pits and some late Roman burials. At the weekends, we opened the site for volunteers and it was a Sunday lunchtime during that long hot summer when Ian asked this question. At that time, l had been researching some of the finds from the Roman Forum site at St Nicholas Circle, which had been excavated between 1971 and 1973 under the direction of Jean Mellor and Terry Pearce. One of the finds l had been working on was a rectangular lead sealing, stamped with the inscription on the obverse with LXXVV, denoting the Twentieth Legion Valeria Victrix, which had been stationed at Chester (Fig.1.) The reverse may have had the stamp of an official lU AQ (Julius Aquila?). At the time, it was one of only a very few objects connected to the Roman military known from Leicester. So, when Ian asked what object l would most like to find, l replied that l would like to find another lead seal with a military inscription.

Now for the spooky part. An hour later, while trowelling up a Roman surface, l found exactly what l had just described. A lead sealing with a stamped inscription LVI, denoting the Sixth Legion, which was stationed at York, with a possible imperial bust on the reverse (Fig.2). Eventually, five more lead sealings were found on the Great Holme Street sites. These included one stamped AVOC (perhaps Ala Vocontiorum), with an official’s signature FL SIM D (? Flavius Similis Decorio) on the reverse (Fig.3). Alae were Roman cavalry units. Two others were stamped with ClAQ, Cohort l Aquitanorum, a Roman auxiliary infantry unit, while another two had private signatures of officials.

So, what were these sealings used for and what was their significance? They were small circular or rectangular lead objects around 2-3cm long used to label consignments. Small ingots made by trapping a binding-wire, in a mould with tapering sides (for ease of removal), and sealing it with a molten tin/lead alloy like solder. This took the impression of letters incised into the bottom of the mould, the ‘obverse,’ while the ‘reverse’ was impressed from above by means of a rectangular die. There might be different stamps depending on who was sending the consignment. When the stamp was of a military unit it didn’t necessarily denote its presence, just that they were sending it. The army was heavily involved in the administration of the Roman province including, for example, mining operations. At the time they were found, the Leicester examples were very unusual and outliers from the known distribution of sealings, which were mainly concentrated in the north, notably Brough-under-Stainmore, where over 100 had been discovered, South Shields and Carlisle. One of the sealings from Brough was stamped with METAL (um) and it is believed they were connected with consignments of lead ore. Lead sealings seem more appropriate to bulkier merchandise, with wax seals perhaps being used for smaller packages. Since then, far more have been found, and more research has been undertaken, notably a PhD thesis by Michael Still in 1995 submitted to the UCL Institute of Archaeology. Michael identified seven different categories: Imperial, Official, Taxation, Provincial, Civic, Military and Miscellaneous. Where they could be dated, they were mainly from the second-third century AD. The majority of Military sealings (i.e. those from Britain) were used to protect their contents and, quite often, to name the person responsible. Lead sealings occur in large numbers in Britain and may be compared with the great quantity (over four thousand) found in the bed of the river Saône at Lyon, where they reflect the activity of the port. Although a wide variety of official sealings is present at Lyon, the great majority are those of private merchants. By contrast, in Britain the great majority of sealings are official; private ones occur, but in a much lower proportion. Although present in Britannia and Gaul, seals with military inscriptions appear not to have been used in all parts of the Empire and none have been found in Germania or Iberia.

But the Great Holme Street finds weren’t the end of the connection between these objects and Leicester. In 1990, Roy McDonnal, an experienced metal detectorist, found a circular lead sealing at Thorpe in the Glebe, in Nottinghamshire, 11 miles north of Leicester. While the obverse was illegible, the intriguing inscription on the reverse was CCOREL. This appears to be an abbreviation of Civitas Corietauvorum, offering further evidence that Ratae Corieltauvorum rather than Ratae Coritani was the Roman name of Leicester. This could therefore be described as a Civic seal, which is an unusual find for Britannia. Michael Still suggests that Civic seals may have been used to show payment of customs dues. Alternatively, this inscription may simply have been used to show the consignment’s place of origin.

Between 2004 and 2006 University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) was carrying out the very large-scale excavations in advance of the Highcross Quarter development (managed by Richard Buckley). Work on Vine Street, directed by Tim Higgins, uncovered a Roman townhouse and it was from this site that three more lead sealings were recovered. These comprised examples from our old friends the Sixth and Twentieth Legions. Two bore the LVI inscriptions while a third was inscribed LXX. But what was really unusual was that one of the Sixth legion stamps also had a stamp on the other side of Llll C, denoting the Third Legion Cyrenaica. While consignments administered by the Sixth and Twentieth Legions might not be unexpected as both legions were stationed in Britannia, the stamp of the Third Legion is remarkable as this legion was stationed in Egypt and Syria. This sealing is unique, not only for naming two legions, but also of legions so far apart: they were both moved by Hadrian, the Sixth Victrix from Germany to Britain, the Third Cyrenaica from Egypt to the province of Arabia (modern Jordan / Syria).

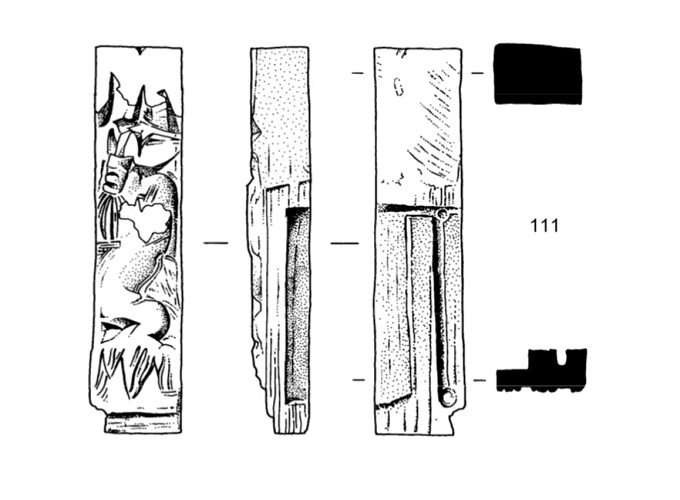

So, is there other evidence linking Leicester with that part of the Empire? Another remarkable find from the same site is an ivory box lid, decorated with a relief motif along the base, which depicts lotus flowers and the iconography of a figure resembling the jackel-headed Egyptian god Anubis. Egyptian soldiers in the Roman army are believed to have favoured Anubis, and as the figure is shown holding lances, there might be a link to military personnel. So why are these two items with their likely Egyptian origins present in Leicester? Perhaps the townhouse was owned by someone from that area or a Briton who had served with the Third Legion in Egypt and had now returned.

Another link with Africa is evidence from a curse tablet, also found during the Vine Street excavations. Here, three people are accused of stealing some silver coins, and the curse calls on the gods to strike them down within seven days in a building referred to as a septizonium. Now a septizonium is a nymphaeum or fountain house which incorporated images of the gods Sun, Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn that represented the days of the Roman week. This fashion originated in Egypt and was promoted by the Emperor Severus Septimius who was born in Leptis Magna, in what is now Libya, and these buildings are thought to be connected with Severus and his dynasty. Leicester is an unusual location for a septizonium, the others being three in North Africa, one in Sicily and one constructed by Severus himself in Rome, which Roman writers identified as a North African monument. It is tempting to link the Leicester septizonium to the time when Severus was campaigning in Britain between AD 208-11, which ended when he died in York in AD 211.

In addition to the artefacts, analysis of Roman burials from Leicester also shows that the population at the time had diverse origins. They were not only from the local area, but from many other parts of the Empire, including some individuals with African origins.

So, fifty years on from the first lead seals being found in Roman Leicester, they still have a story to tell, whether it is of the trading links the Civitas had with other parts of the Empire or in contributing to the evidence about the ethnicity of some of its citizens. Together with other evidence from burials and artefacts, Roman Leicester appears to have had a diverse multi-cultural population similar to its modern counterpart.

Dr. Patrick Clay (2025)

I would like to thank Mathew Morris and Nick Cooper for their help, comments and information in the preparation of this blog.

Further reading

P. Clay, (1980) ‘Seven inscribed leaden sealings from Leicester’, Britannia 11), 317–320.

H.E.M. Cool (2009) ‘The Small Finds’ 152-228 in M.Morris, N.J.Cooper and R.Buckley (eds) Life and Death in Leicester’s North-east Quarter: Excavation of a Roman Town House and Medieval Parish Churchyard at Vine Street, Leicester (Highcross Leicester) 2004-2006 SK 583 049 Volume 2: The Specialist Reports. (Available through the Archaeological Data Service)

M.Morris. (2022) ‘Leicester and Roman Africa. Exploring ancient multiculturalism in the Midlands.’ Current Archaeology 388, 29-33.

M. Morris, M. Codd and R. Buckley, (2011) Visions of Ancient Leicester Reconstructing Life in the Roman and Medieval Town from the Archaeology of the Highcross Leicester Excavations. University of Leicester

R. Buckley, N.J. Cooper and M. Morris (2021) Life in Roman and Medieval Leicester. Excavations in the Town's North-east Quarter, 1958–2006.Leicester Archaeology Monograph 26. University of Leicester.

R.S.O. Tomlin (1983), ‘Non Coritani sed Corieltauvi’, Antiquaries Journal 63 353-5.

R.S.O. Tomlin, and M. W. C. Hassell, (2007) ‘Inscriptions’ Britannia 38 345-365.

Roman lead seal from Vine Street, Leicester excavations (2005) with stamped on reverse with Llll CYR Third Legion. Brit. 38.17 13b - fig. 13(b). Photo: R.S.O. Tomlin ULAS. https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/Brit.38.17