Sunday 29 September 2024

Salt Ways In Leicestershire

LAHS Member Bob Trubshaw explores the history of these ancient trackways.

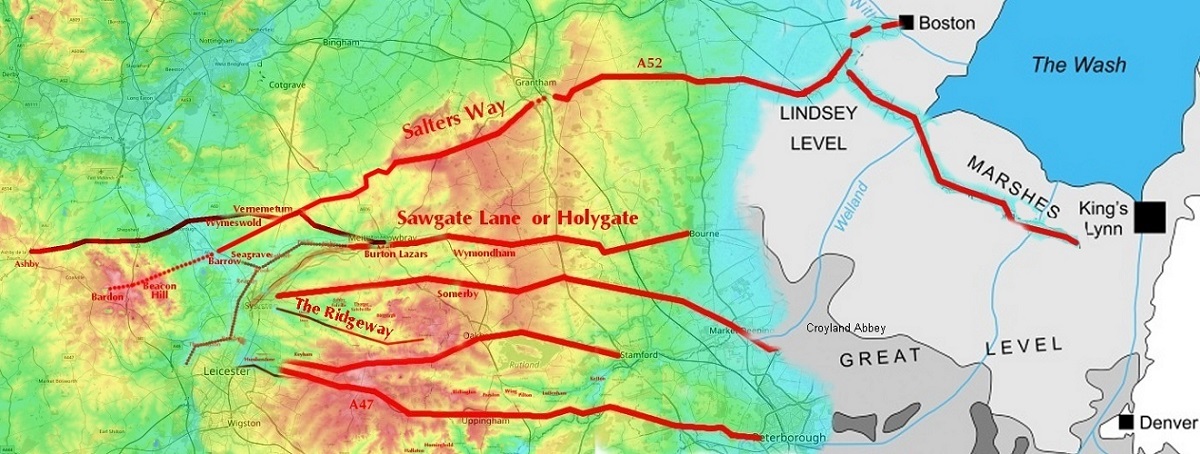

Numerous east-west routes in north-east Leicestershire continue into Lincolnshire and on to the Norfolk coast. Place-name evidence reveals they were once thought of as salt ways. They once transported wool in great quantities and were used by countless pilgrims heading for Walsingham. And these routeways perhaps originate with Neolithic farming practices.

The heyday of wool

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries a great many wagonloads of wool made their way from the East Midlands to the east coast ports for export to the Continent where it would be spun and woven.

Some, perhaps most, of these loads would be taken to recognised ports such as Boston and Bishop’s Lynn – as King’s Lynn was known until 1537 – and the necessary taxes paid to the Customs officers. However north-west Norfolk also has a great many less formal loading places, such as Burnham Overy Staithes, Thornham and little lanes running to obscure creeks, such as to the west of Castle Rising. Some of these informal loading places were even known as Shepherd’s Ports. For example, current OS maps still show Snettisham Beach as ‘Shepherd’s Port.’ Anyone looking to dodge the Revenue men would have plenty of options along that coast. And there were very good reasons to dodge the Revenue men as the wool tax imposed in the thirteenth century by Edward, I deemed that a third of the proceeds of a sack of wool went to him, another third went to the church and just one-third to the farmer.

Once the wool had been unloaded these wagons would return to the Midlands. A return load would increase the waggoner’s profits. The Fenland was well-suited to evaporating salt from brine. And salt was needed in considerable quantities throughout Britain to preserve meat – such as bacon – and for making cheese.

The heyday of pilgrims

Before the 1530s other people also travelled along the routes used by the wool wagons. They weren’t doing it to make a profit. But for the good of their souls. They were pilgrims heading for Walsingham, one of the leading pilgrimage destinations in England. Pilgrimage came to a sudden end in the 1530s once Henry VIII instigated the Dissolution of the monasteries and destroyed the shrines which were the focus of pilgrims' devotion.

Sawgate Lane runs east-west to the south of Melton Mowbray, following the south bank of the River Eye. It is part of a former Roman road from Leicester, along the Wreake valley to Kirby Bellars, then due east to the Roman iron-extraction site at Thistleton where it meets Ermine Street.

One of the farms alongside Sawgate Lane is still known as Holygate Farm. This gives a clear indication that Sawgate was once also known as Holy Gate. Just to clarify. Saw is a contraction of ‘salt’ and ‘gate’ here is the Scandinavian word gata which means ‘road.’ If you know Leicester city centre then you’ll know Braunstone Gate, Belgrave Gate and Gallowtree Gate. Nothing to do with wooden gates and such like as 'gate' refers to the roads leading to what are now suburbs but originally separate villages.

The decline of wool and the heyday of salt

By the sixteenth century, the quality of English wool was in decline, presumably because sheep were now being bred for meat required by ever-growing urban populations. High-quality wool was instead sourced from merino sheep on the Iberian Peninsula.

As the wool trade died off the salt was still needed. So, the routes became known as 'salt ways' rather than 'wool ways'. The road from Leicester to Uppingham (now the A47) brought limestone from Rutland for building as well as salt. New return loads were needed for the wagons heading eastwards. Charnwood slate, presumably purchased from stone dealers in Leicester, was used extensively for roofing and, from the early eighteenth century, for gravestones. Churchyards tell us that Charnwood slate was taken in large quantities along the Salters Way to Grantham where it was seemingly traded for malt (see Trubshaw 2022; 2023).

The survival of salt in place-names

Coastal salt pans were a labour-intensive way of producing salt. Starting in the 1840s salt was mined in Cheshire and transported by rail. The price fell dramatically, making evaporation pans uneconomic. The salt ways dropped out of use in Britain and mostly became forgotten.

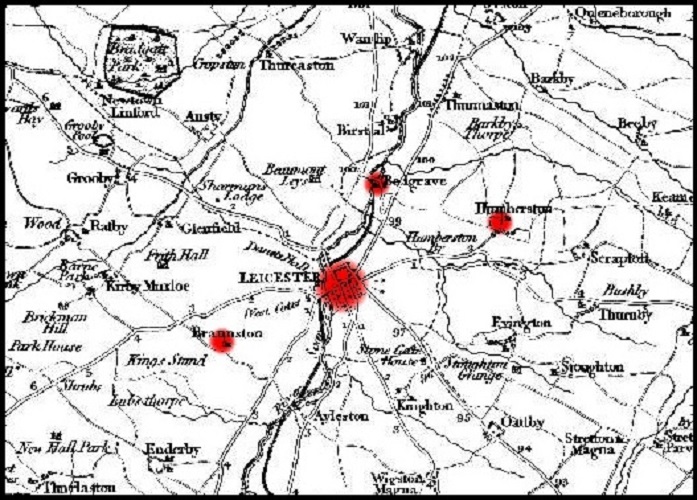

The name Sawgate Lane is still used for the road near Melton. And, thanks to Barrie Cox's comprehensive study of the minor place-names of Leicestershire and Rutland, we have evidence for many salt way names which are no longer current. So we can work out that Sawgate Lane seems to have followed the minor road and tracks running from Leicester to Thurmaston (where the Saltergate is mentioned as early as the 1320s or 1330s), then Barkby (where Saltergate is mentioned in the 1470s or 1480s), on to Rearsby (with a Salters Close in 1648), through Brooksby and Rotherby to Frisby on the Wreake. This route was bypassed in the 1760s when a turnpike was constructed, now known as the A607. From Frisby, Sawgate went to Kirby Bellars (where a Saltgate is mentioned in a document of 1404). The route goes through the parish of Eye Kettleby, then heads due east to Burton Lazars and thence to Wymondham before crossing into Lincolnshire at South Witham (which is on Ermine Street) then continues via Castle Bytham to the Fens.

Bear in mind that before the Reformation Croyland Abbey produced most of its income from salt pans. There’s tantalising evidence of an all-but lost routeway from the Fosse Way near Cosby, which was the meeting place of the Guthlaxton Hundred, heading west towards Earl Shilton and on to Sutton Cheney. As Peter Foss noted back in 1991, Sutton Cheney was the most westerly possession of Croyland Abbey.

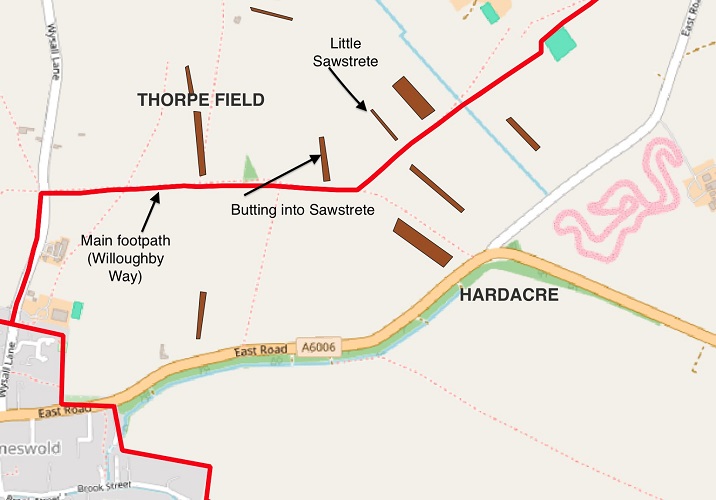

Seemingly the road from Ashby de la Zouch to Melton (now the B5234 and A6006) was once a salt way because there’s a reference to a Saltstrete or Sawstrete in Wymeswold. This is mentioned in 1412, again in 1543, and finally in a seventeenth century land transfer. Ongoing work by Richard Ellison identified the fields in these documents. They straddle a still-extant footpath which runs parallel to the post-Enclosure Award lanes.

Uppingham Road – now the A47 – was undoubtedly a route used for the transport of wool and salt. However, it is 'shadowed' by a parallel salt way as a Salter's Cross in Luffenham is mentioned in 1615. Plausibly a minor road through Ridlington, Preston, Wing, Pilton, Luffenham and Ketton (running roughly parallel to the north of the A47) could have been a salt way.

Nearer to Leicester but still just to the north of the A47, Keyham once had a Salters Close and Humberstone had a Saltersford Bridge – still so called as late as 1835 – both on a route into Leicester that extends eastwards to Tilton on the Hill, Braunston in Rutland and on to Oakham.

Intriguingly saltways as it were 'bypass' market towns and former market towns such as Wymeswold. This was to avoid paying tolls on produce which was not going to be sold in those towns but was headed for more distant places.

Before wool and salt

The sheer number of east-west routes running almost parallel suggests there was much more to them than merely salt ways. Such ‘skeins’ of near-parallel routes suggest a much older origin. One of the best clues is that some follow valleys – as with Sawgate Lane – or the ridge tops – as with the Salters Way and the Ridgway.

I’m not the first to make this suggestion. Back in 1988 the very eminent historian Harold Fox referred to the 'bundled tracks' running east from the Soar valley and over high east Leicestershire. He thought they were evidence of transhumance.

Transhumance is the seasonal movement of livestock between different summer and winter pastures. The underlying problem is having enough grazing to keep livestock alive during the winter. Eventually haymaking alleviated the problem, while manufactured feeds are a modern solution to the problem. But traditionally pastoral farmers exploited different types of terrain and grazing on a seasonal cycle.

Usually, but not always, the summer pastures were on higher ground. In many languages there are words for the higher summer pastures, and frequently these words have been used as place names: e.g. hafod in Wales and shieling in Scotland, and alp in German-speaking regions of Switzerland.

Neolithic monuments on the Marlborough Downs in Wiltshire – such as Avebury and the causewayed enclosure and long barrow near to Alton Barnes – were connected to similar sarsen stone chamber tombs – such as Kit’s Coty House – in the north of Kent, by a transhumance route running alongside the river Kennet and the Thames which follows the chalk uplands through the Chilterns, the North Downs and along the north of the Weald. The route is still in use as the M4, M25 and M20.

Plausibly the Leicestershire saltways follow routes linking the Fens with the high ground of east Leicestershire as this would offer similar diversity of seasonal grazing.

Leicestershire has a clear example of early medieval transhumance as Somerby, on high ground to the south of Melton Mowbray, means the ‘summer settlement.’ The –by ending is from the tenth or eleventh century. But it may have been Somerham or Somerton before that.

As Stuart Evans has described in a previous LAHS blog, there’s evidence for prehistoric activities along the Leicestershire transhumance routes. The western end of the Salter’s Way passes through Ver Nemeton – the Iron Age Great Sacred Grove – and the bearu ('sacred grove') which gives its name to Barrow on Soar, before continuing west to Beacon Hill – a known Bronze Age hill fort – and to Bardon Hill – a presumed Bronze Age and maybe Iron Age hill fort.

Sawgate Lane seems to continue west to Seagrave, which is from the Old English seath graf or ‘sacred pool in a grove’ and then on to Barrow on Soar, with its own sacred grove. While seath graf and bearu only date back to the Anglo-Saxon period we can confidently assume that these sacred sites date back to the Iron Age or earlier.

In the mid-1990s a major Bronze Age ritual site was discovered at Eye Kettleby, right on Sawgate Lane. And in 2016 geophysics revealed extensive Iron Age and Roman settlements to the south of Sawgate Lane. Very recently a scatter of undated but probably prehistoric features were identified east of Melton but south of the River Eye close to Sawgate Lane. Finds included a Bronze Age thumbnail scraper. Topographically the location would fit an Anglo-Saxon hearg or 'harrow' – a pre-conversion ritual site previously used by Iron Age and Roman people.

A prehistoric origin for these transhumance routes – much later known as salt ways – neatly explains why there are so many of them ‘bundled together’ as Harold Fox noted. In prehistory there were no hedges or other boundaries so routeways could happily wander over the terrain. The prehistoric landscape would often be wooded. But rarely the sort of dense woodland of recent centuries. Rather it was managed for woodland grazing with plenty of clearings. And some of those clearings would be linear, creating as it were corridors through the trees. There was nothing to stop prehistoric routeways becoming several such corridors in close proximity ‘skeining’ their way over quite long distances. Once created those routes would remain in use even after medieval great fields were enclosed and often after the eighteenth-century Enclosure Awards brought about much smaller fields.

So, should the title of this blog have been 'Salt ways in Leicestershire' or should it have been 'Neolithic transhumance routes in Leicestershire'? The evidence for salt ways is very clear. Whereas the evidence for prehistoric routes is, so far, just tantalising glimpses. But that is as good as we could ever expect.

Bob Trubshaw

Email: bobtrubs@indigogroup.co.uk

This article is based on a video published on Bob’s youtube channel which can be accessed here.

Acknowledgements

This blog would not have been possible without the work of Barrie Cox and Harold Fox. My thanks to Richard Ellison for locating the Saltsrete in Wymeswold. Richard Clark kindly shared unpublished information about recent discoveries associated with the currently-ongoing construction of the Melton Mowbray Distributor Road.

Coloured contour maps are from en-gb.topographic-map.com

Sources

Barrie Cox, The Place-Names of Leicestershire, (English Place-Name Society [seven volumes 1998 and 2016]).

Evans, Stuart, 2024, 'The Iron Age Landscape of the Salt Way'

Peter Foss, 'The Anglo-Saxons in Leicestershire'. Lecture to Leicestershire Fieldworkers 9th March 1991.

H.S.A. Fox, 'The people of the Wolds' in M. Aston et al (eds) The Rural Settlements of Medieval England (Oxford 1989) p88.

Tom Lane, Mineral from the Marshes: Coastal Salt-making in Lincolnshire (Lincolnshire Heritage 2018).

Sidney Pell Potter, A History of Wymeswold (1915) pp1–2; 80.

Bob Trubshaw, 'Charnwood slate gravestones and eighteenth-century trade routes', Leicestershire Historian, No.58 (2022) p37–42.

Bob Trubshaw, YouTube video 'Charnwood slate gravestones and eighteenth-century trade routes'

Bob Trubshaw, YouTube video '"Following the money" along medieval bypasses'

Transhumance - Wikipedia- en-wikipedia.org/wiki/Transhumance

Looking east along the part of Sawgate Lane to the south of Melton Mowbray. Photo by Bob Trubshaw (c.2022)