Sunday 24 March 2024

The Iron Age Landscape of the Salt Way

LAHS member Stuart Evans considers the Salt Way, an ancient route running from Donington in Lincolnshire across to Barrow upon Soar in Leicestershire and through a review of the archaeological evidence, discusses its possible Iron Age origins.

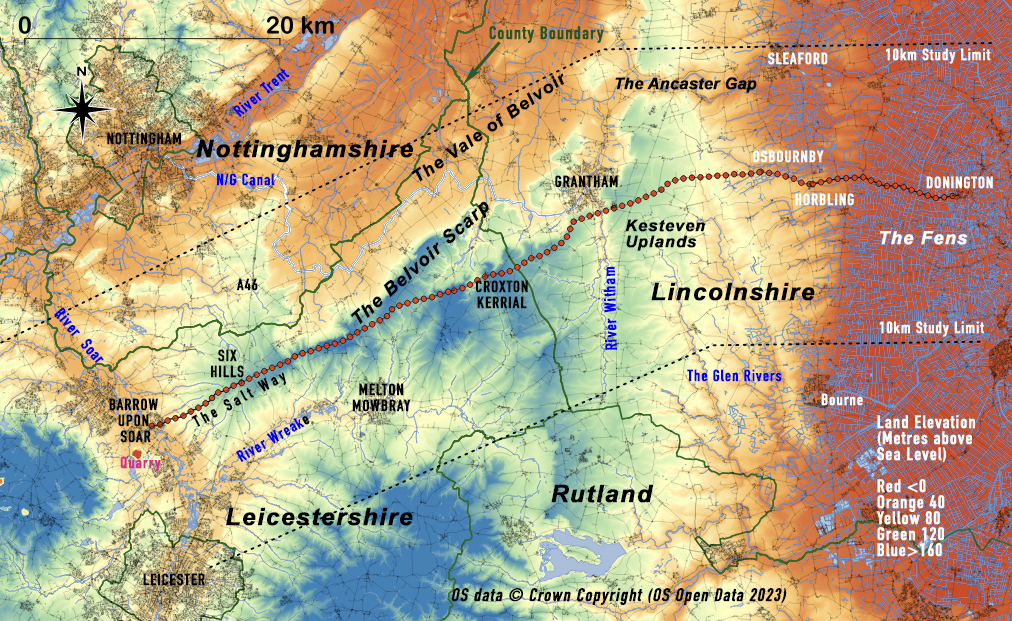

Throughout the ages, there have been several “Salt roads” transporting salt from the Lincolnshire coast into Leicestershire. The most northerly of these routes is known locally as “The Salt Way”. The course of the road runs westwards from Donington, in Lincolnshire, across the Fens to Horbling, over the Kesteven Uplands, crossing the river Witham to the south of Grantham, into Leicestershire at Croxton Kerrial, then along the Belvoir Scarp to Six Hills on the A46 and down to Barrow-upon-Soar (Figure 1).

CW Phillips (Phillips 1934), ascribed the importance of this road to salt transport in the Iron Age1 and used the term Salters Way to describe the road. However, the road clearly had features of Roman construction and in his seminal text on the Roman Roads of Britain, Ivan Margary classified it as a Romanised “Old Salt Way” (Margary 1955, page 165).

This article looks at the more recent archaeology 10 km on either side of the road (Figure 1) and considers whether the roots of the Salt Way are in fact Iron Age or more of Roman origin. This review raised a series of questions.

Where was the source of the salt in Iron Age Lincolnshire?

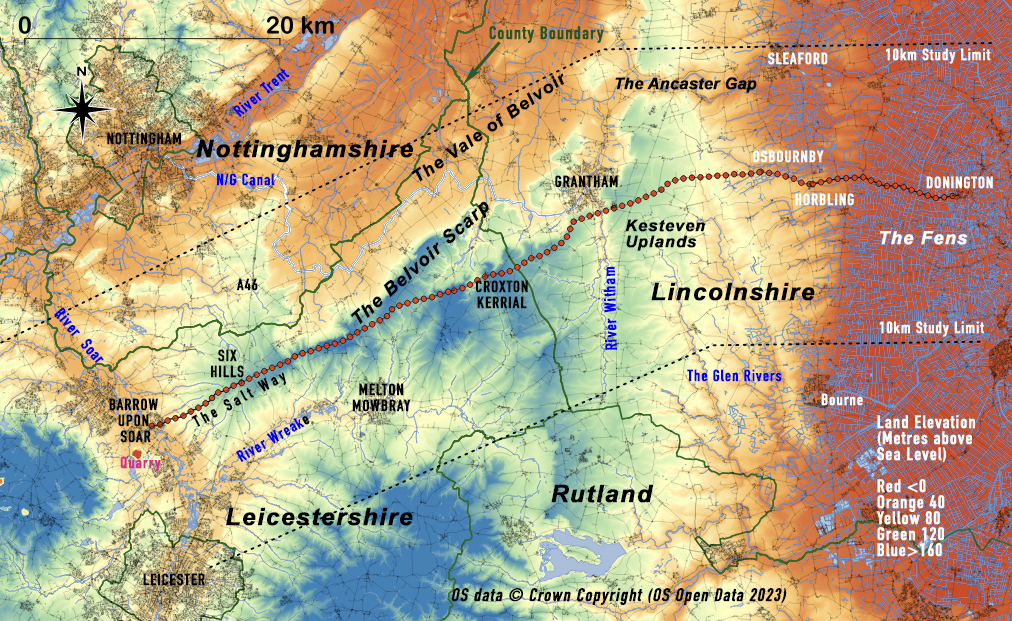

Before the drainage of the fens, these marshlands were described as “The site of a battle between marine waters of the sea and the fresh waters of the rivers”. Sometime around 1000 BC, the climate of Britain became cooler and wetter, sea levels rose, and the previously freshwater Lincolnshire fenlands were turned into a marine environment. Seawater came in from the coast along creeks up to the western fen edge at Horbling and created a salt marsh. Salt was extracted from the seawater at these creeks in locations known as Salterns. In the modern drained fen, the silted-up ancient creeks can still be seen. They stand about a metre higher than the surrounding land and are called Roddons (Figure 2).

The Fenland Management Project carried out in the 1970's and 80's, found the distinctive crude briquetage pottery used by the early salt makers at the edges of the fen (Figure 2).

An excavation carried out in the 1970’s at Billingborough indicated that salt-making took place between 800 and 400 BC (Chowne et al 2001). Another site further north at Helpringham has also been excavated indicating that salt-making took place here between 400 and 100 BC (HER MLI83363).

As the sea levels fell from their peak in the middle of the first millennium BC, the marine environment retreated and the salt extraction slowly moved eastwards. By the Roman period, an area east of Donington became the centre of salt production.

Where was the salt exchanged?

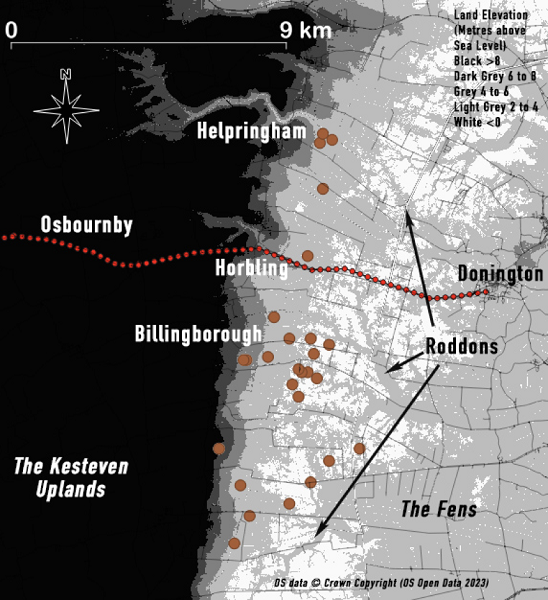

Folklore says that the salt was transported along the Salt Way, over the Soar and into the Midlands, but there is little evidence to support that statement; quite the contrary. Inland sources of salt in the Iron Age are recorded in Worcestershire and further north in Cheshire. The manufacture of salt from these sources was less demanding than extracting it from seawater and a wide system of exchange developed from these inland sites (Morris1994). The inland sites used characteristic briquetage pottery vessels to transport salt which allowed archaeologists to detect the distribution of the salt. This reached well into the north and west of Leicestershire. In fact, in 1993/4, 15 fragments of a briquetage salt transport vessel were found at Mountsorrel in the west of the study area (Figure 3, 2). This find was in a late Iron Age context (MLE721).

It is more likely that the movement of northern fenland salt was to communities in east Leicestershire and south Nottinghamshire. However, it is thought the fenland salt was transported in containers made of organic material, probably reed baskets, making Iron Age distribution difficult to detect (Lane and Morris 2001, page 459).

Where were the Settlements along the Salt Way?

The communities along the Salt Way were located in two types of settlement sites. The most common were domestic enclosures2 usually surrounded by a ditch. The second are commonly known as ‘Hillforts’3, these are enclosures on higher land surrounded by a system of banks and ditches.

The Historic Environment Record4 (HER) has 82 recorded Iron Age domestic enclosures within 10 km of the Salt Way (Figure 3, white and black circles). There are few reported domestic enclosure sites on the track itself with just 2 sites on the west bank of the river Witham and 3 at the western end of the route.

The largest area of recorded enclosures is 4 to 5 km south of the Salt Way, between Melton Mowbray and Leicester, down the Wreake Valley and at its confluence with the river Soar. There is also a dense distribution to the east of Sleaford, including one large site with a palisaded enclosure (MLI60583). Only 3 domestic enclosures (Figure 3, 1) are above the 120 metre contour and these are all located at Waltham-on-the-Wolds where significant evidence of smelting has been found. These were probably exploiting the local source of ironstone.

Where recorded, the dates of most of these settlements are generally relatively broad, with most in the mid to late Iron Age and many also show a Roman phase. A few (the white circles) had indications of early Iron Age features.

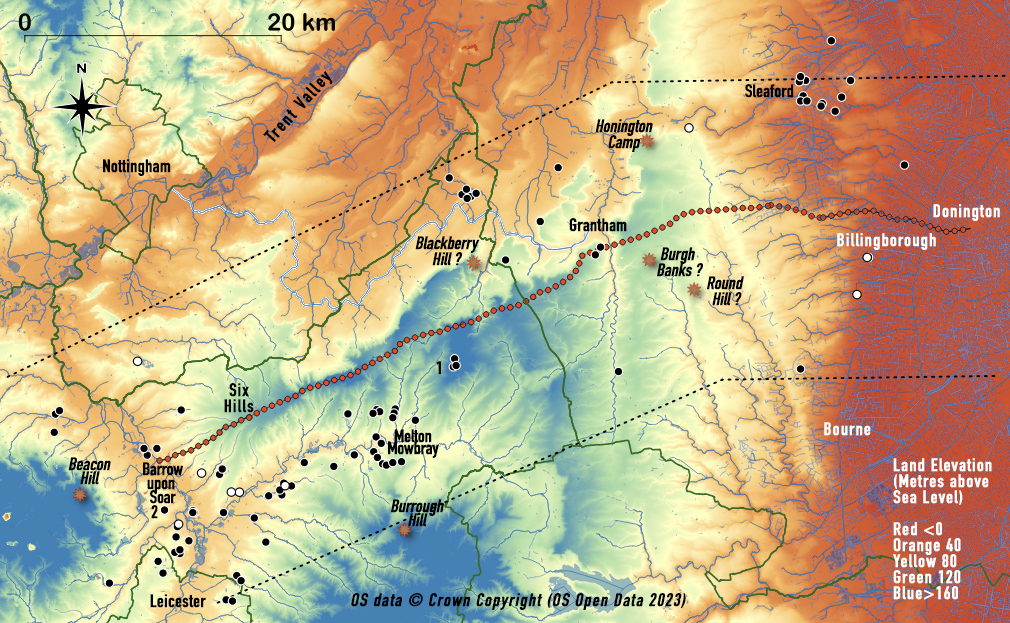

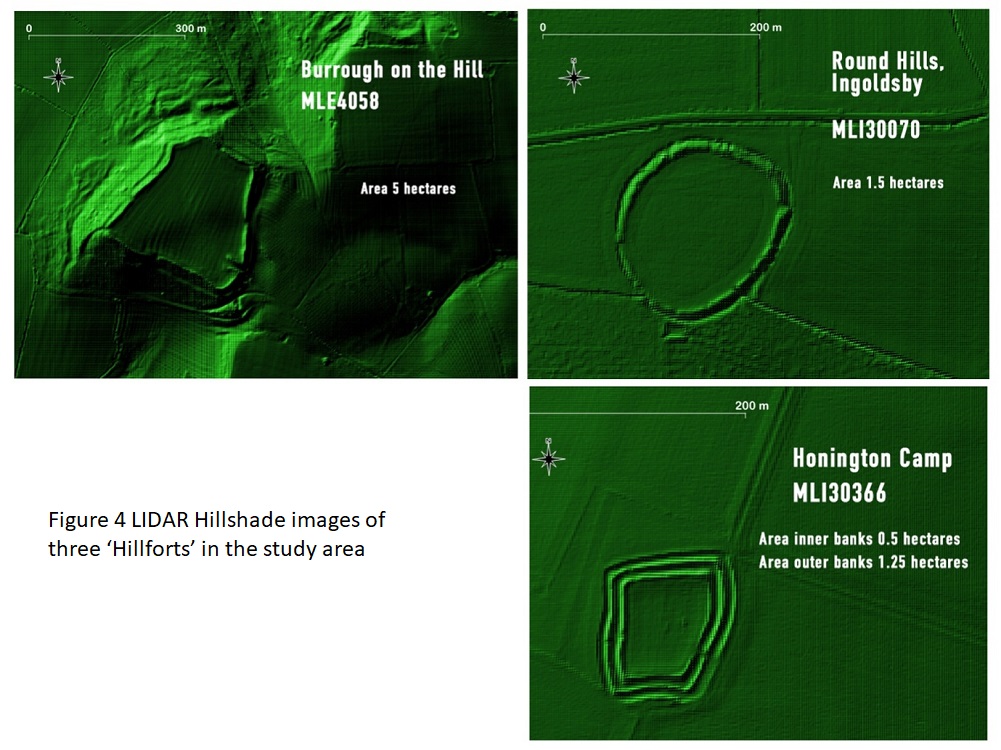

The location of six recorded 'Hillforts' are shown in Figure 3, although three have queries over their origins (Marked ?). Only 1 has been investigated in any detail, Burrough Hill (MLE4058). The earthworks of this 'Hillfort', along with Honington Camp (MLI30366), and Round Hills (MLI30070) are still clearly visible using LIDAR (Figure 4) but neither of the latter 2 has been excavated. All are on high points of land.

The features at Burgh Banks (MLI34015) and Beacon Hill (MLE1132) can still be seen but are very eroded. At the latter site, Bronze Age artefacts have been found that would suggest an earlier date. Blackberry Hill (MLE3377) lacks evidence.

The only indication of salt use at any of these 'Hillforts' or domestic enclosures is the briquetage vessel found at Mountsorrel. There is no other evidence recorded. This lack of evidence is hardly surprising given the soluble nature of salt and the instability of the organic material of the fenland transporting containers.

Salt was in widespread use at the time for preserving food and other items. It would have been essential to these settlements and a valuable commodity.

Discussion

The factors influencing the tracks of early roads are numerous - social, geological, ritual, economic - and in earlier times influenced as much by animal movement as by people. These many factors have recently been reviewed (Chadwick 2016 and Bell 2020). Considering all of these aspects the evidence that the Iron Age Salt Way was used as a continuous route from the fen edge to the Soar is weak.

The only distinctive feature of the Salt Way is the ground elevation. Figure 3 shows that it runs almost along its entire length on the higher land; a track formed where the land is well drained and firm under foot/hoof. It only drops down to cross the river Witham and at each end of the track.

However, salt produced at the fen edge probably moved west by a variety of routes throughout the 800 years of the Iron Age, any of which could have been used at different times. The salt produced at Billingborough may well have travelled across the Kesteven Uplands but how did its journey continue? At the river Witham it could have gone 3 ways, north-west to the communities in the Trent valley, across directly to the Wreake/Eye valley or may have gone down the river, north to Lincoln.

Other factors may also have come into play, the tribal centre formed at Sleaford in the later Iron Age may have governed the production and movement of salt, most likely using the Ancaster Gap as a route. The Soar and Wreake valleys may well have obtained salt from salterns at the fen edge further south around Bourne and the Welland valley. We also have one piece of evidence suggesting that inland salt may have been used in the Soar valley.

The Iron Age was a turbulent time, the interrelationship between the fen edge communities and those of Leicester and east Leicestershire is a fascinating aspect of the period. The tribal structure that emerged in the late Iron Age with these 2 communities could well have involved salt as a “Political” commodity. But, the Salt Way was forged by the Romans to link the Fosse Way to Ermine Street and then onto Donington where there were major Roman salterns. The Salt Way is therefore an appropriate name but its Iron Age roots are far from certain.

Footnotes

- For this blog, the Iron Age is taken to be 800 BC to 42 AD.

- A domestic enclosure is defined as “A site with significant ditches or other earthworks confirmed as Iron Age by associated finds of domestic features”. This definition excluded sites detected by Cropmarks or Magnetometry that had not been further investigated.

- There is debate amongst archaeologists over what constitutes a ‘Hillfort’, for this blog the term ‘Hillfort’ is colloquial, maintained in quotes and only used for features recorded as such within the HER.

- References to specific records from the HER are highlighted in red and hyperlinked. These are updated periodically and this document refers to the 2023 records.

References

All references are highlighted in blue and hyperlinked to the reference abstract.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to the various county Historic Environment Officers who maintain the HER database and have patiently answered my many queries.

Copyright

LIDAR Data was downloaded from the DEFRA survey and is subject to the Open Government Licence v3

Stuart Evans

Contact: stuartevans4@icloud.com

The geographical features along the Salt Way. Contains OS Open Data © Crown Copyright (database right) 2023 Reproduced under Open Government Licence 3.0. Annotated by Stuart Evans (2024)