Sunday 23 March 2025

Resolving the Flaws of Previously Published Folville Pedigrees

Guest Blogger, David J. Lewis, traces the genealogy of this medieval Leicestershire dynasty.

Introduction

Whilst researching the manor of Ashby Folville for a book I am currently writing, I embarked on a four-month-long project to transcribe and translate the folios pertinent to the Folville manors of Ashby Folville and Teigh (Rutland) contained in the 15th-century Woodford cartulary held in the British Library.[1] Cartularies were created by wealthy families or ecclesiastical institutions to document entitlement to their lands through the inclusion of relevant charters, deeds and other documents. In the case of the Woodford cartulary, they date back to the twelfth century.

A deed contained in the cartulary, written in Medieval Latin and dated 1343 at Ashby Folville, raised questions regarding various previously published Folville pedigrees, particularly in relation to the parentage of the 14th-century criminal gang of Folville brothers (who were the subject of a recent LAHS blog[2]) and their eldest brother John, lord of the manor of Ashby Folville. Whilst my revised Folville pedigree was originally published in the Genealogists Magazine in December 2022,[3] a similar article presented via this blog provides accessibility to a wider audience.

The Folvilles held their land of the honour of Huntingdon

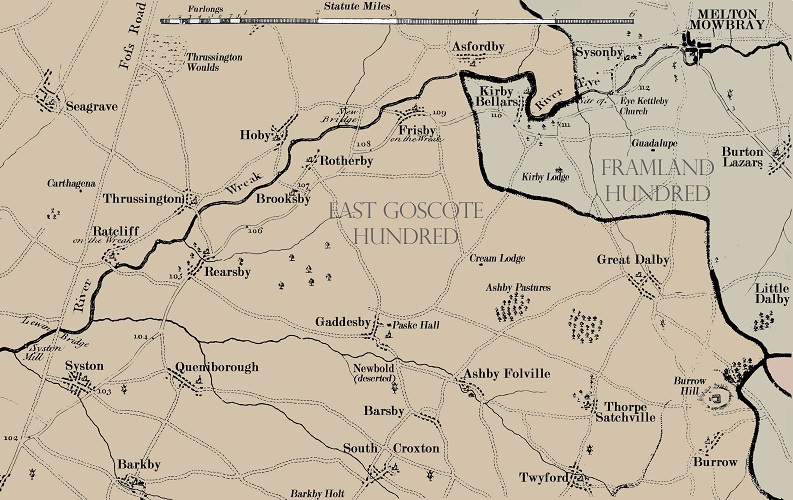

At the time of Domesday, Countess Judith, the conqueror’s niece, held vast swathes of land across several east-midland counties and East Anglia. The countess was the widow of the Saxon earl, Waltheof of Huntingdon and Northumbria, who was executed 30 May 1076 following a revolt against William I.[4] Countess Judith’s Leicestershire holdings included around 1,000 acres in Ashby [Folville], 120 acres in the adjacent hamlet of Newbold (now deserted) and a similar acreage in the neighbouring village of Gaddesby.[5] Upon the marriage of Judith’s daughter, Matilda, the Huntingdon estates fell to Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim who became David I of Alba (the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland) in 1124.[6]

Stephen de Blois (r.1135-1154) claimed the English throne when Henry I died without a male successor, his only son having been a victim of the ‘White Ship’ disaster of 1120.[7] David I - who supported his niece’s (Henry I’s daughter, Matilda) claim to the English throne - rebelled against Stephen whereupon his Huntingdon earldom and estates were confiscated. The Alban king subsequently invaded the north of England to reclaim Northumbria and the Huntingdon earldom for his son Henry. Although Stephen marched his army north to confront the incursion, bloodshed was avoided when a treaty was made at Durham to restore half the Huntingdon lands and the earldom to the royal heir. Henry succeeded his father as 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, but the first creation of the earldom became vacant in 1237, when John of Scotland, 9th Earl of Huntingdon (great-grandson of David I), died without issue. By the late thirteenth-century, the Huntingdon estate was held by Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale (through his father’s marriage to Isobel de Huntingdon). As a great-great-grandson of David I of Scotland, he failed in his claim to the Scottish throne, but he was the grandfather of the fabled Robert the Bruce, who as King of the Scots gained independence for Scotland in 1328.

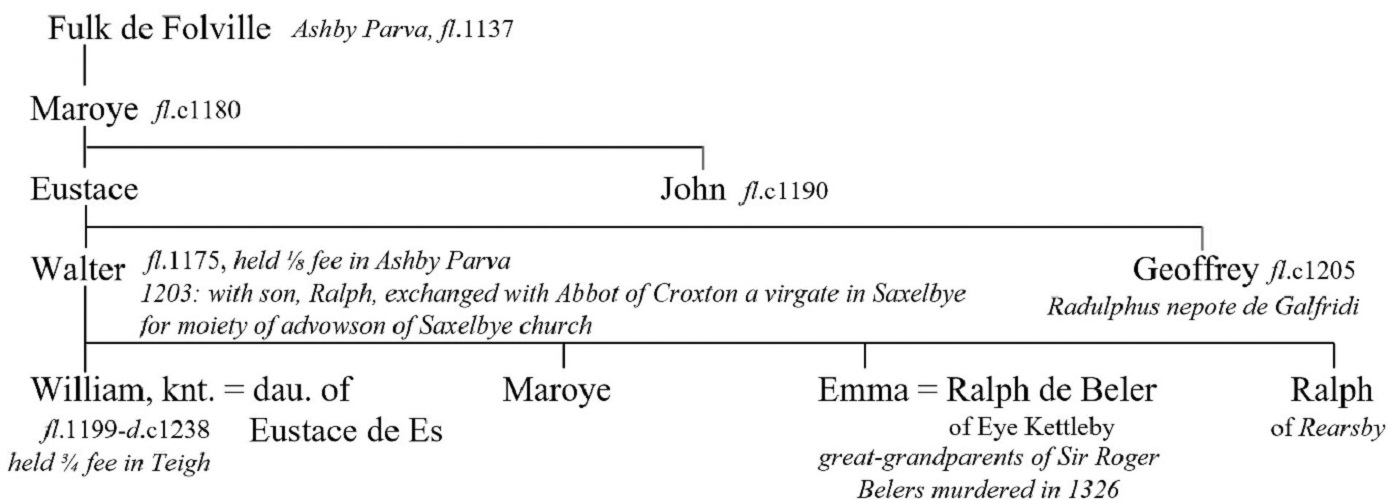

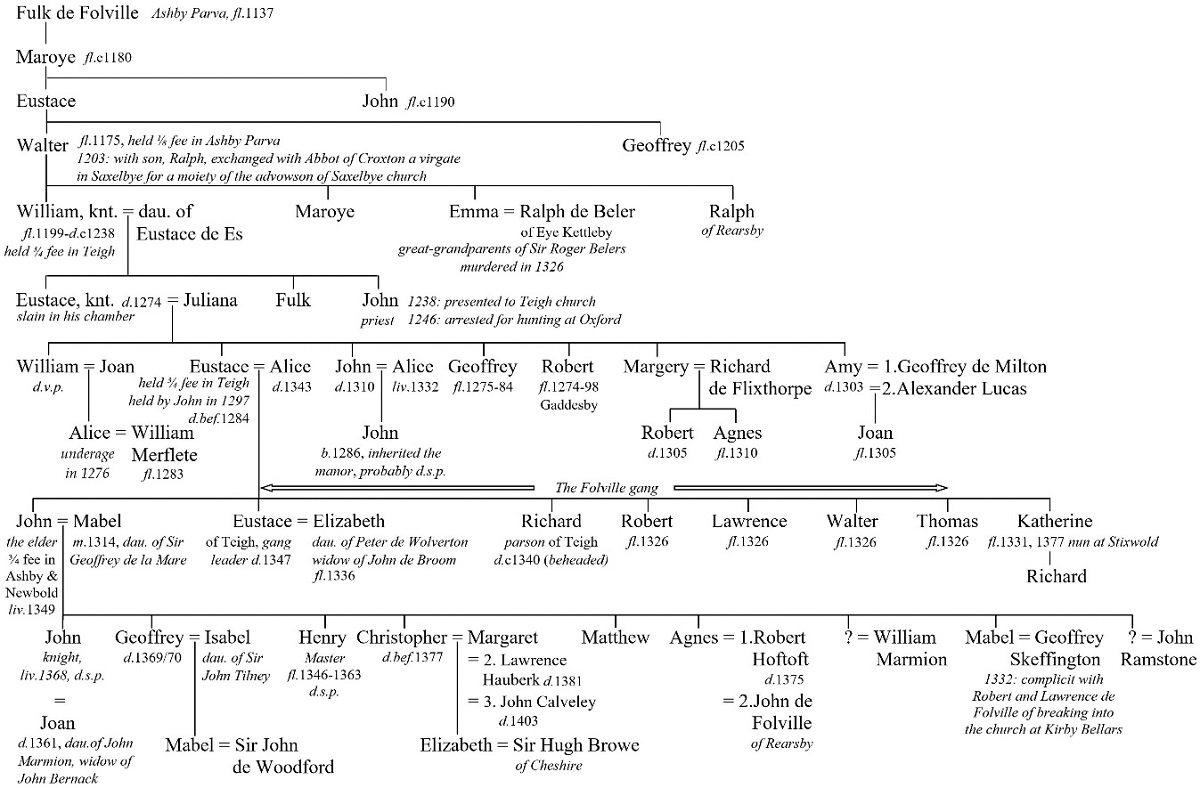

The Early Folvilles

The Folvilles originally came from Foleville in the Picardie region of France situated some sixty miles north of Paris and in 1137, Fulk de Folville held the lordship of Ashby and Newbold with land in Gaddesby of the honour of Huntingdon.[8] The Folville name was subsequently appended to both Ashby and Newbold to differentiate them from other similarly named places in Leicestershire.[9] The Folvilles also possessed the manor of Teigh some twenty miles distant in Rutland. The Folville manors subsequently passed to successive male heirs, namely, Maroye, Eustace, Walter then Sir William de Folville who in 1210 held ¾ of a knight’s fee in both Ashby Folville and Teigh.[10] However, these became forfeit when William was imprisoned for siding against King John in the first Barons’ War (1215-1217).[11] His freedom and restoration of lands were subsequently secured upon payment of thirty marks on the condition he entered into marriage with the daughter of Eustace de Es,[12] and when Henry III’s sister married the Roman emperor Frederick II in 1237, Sir William de Folville was levied four marks for two knights’ fees held of the honour of Huntingdon in Ashby Folville and Newbold Folville.[13]

Murder most foul at Ashby Folville

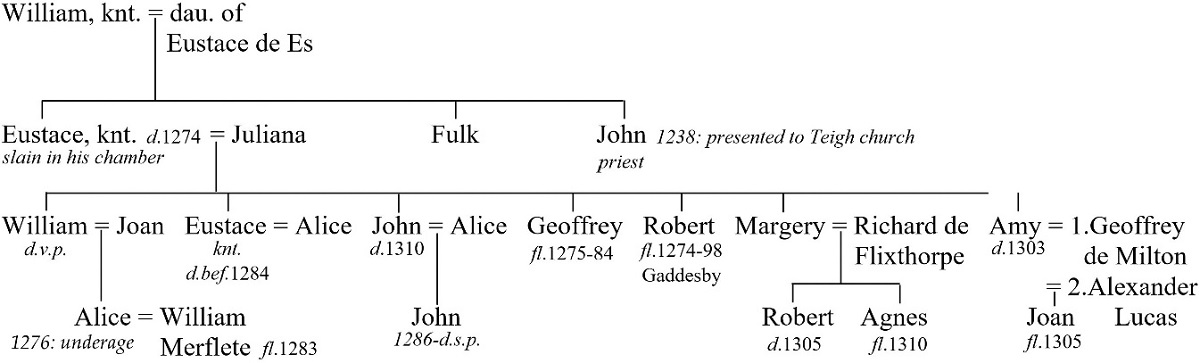

William de Folville presented his son, John, to the priesthood of Teigh church in 1238,[14] and soon after, a charter confirms William’s eldest son, Eustace, succeeded to the manor as, ‘for the salvation of his soul and the souls of his ancestors, and his heirs’, he reconfirmed five shillings in rent to Nuneaton priory due from a virgate of land in Ashby Folville previously granted by his father.[15] Another of William’s sons is identified in a quitclaim (a document relinquishing entitlement to land or property) in which Henry de St Mauro confirmed to Fulk de Folville a virgate of land in Ashby previously held from his father.[16] Upon the marriage of his daughter, Margery, to Richard de Flixthorpe, Eustace granted them twelve and a half virgates of land in Ashby Folville along with the services of eleven bondsmen, one of whom was Ralph Capron, who played a deadly role soon to be related.[17]

Sir Eustace de Folville sided with Simon de Montfort against Henry III in the second Barons’ War (1264-1267). Having participated in the battle of Evesham and the defence of Kenilworth castle, the Folville manors were once again confiscated, but later restored upon Eustace’s agreement pay a fine to the value of five years rent and to stand firm by the Dictum of Kenilworth issued by the king to offer repentant rebels terms for reconciliation.[18] Undoubtedly, this created hard times for Eustace who probably took it out on those around him and this may have prompted his murder in his chamber at Ashby Folville around midnight on Saturday, 24 November 1274.[19]

Eustace’s death triggered several claims and counter-claims on the estate. The guardians of Robert, the son (then in his minority) of Richard de Flixthorpe and Margery, set in motion an assize of mort d’ancestor to secure Robert’s right to inherit the lands given to his father upon his marriage.[20] Eustace’s widow, Juliana, entered pleas against sons John, Geoffrey, Robert and others, demanding entitlement to a third part of the estate in dower.[21] Alice, the daughter of William (the eldest son of the murdered Eustace who predeceased his father), entered a plea against her uncle Eustace (the late William’s brother) claiming she had been disseised (dispossessed) of the manor of Ashby. Eustace countered that having taken seisin of the manor immediately after his father’s death, Alice could not plead disseisin as she never had it in the first place! Being underage, Alice argued that as daughter and heiress of the eldest son, Robert V de Brus (from whom her grandfather held the manor) took the manor into his hands as her guardian, but the justices found in favour of the uncle. Eustace also brought a plea of disseisin against Alice for the lands in Teigh. Alice argued (mentioning her mother, Joan) that she entered upon the property in Teigh exactly a week after her grandfather’s demise and this time the decision favoured Alice.[22] In 1277, John de Folville brought a plea against his widowed mother, Juliana, accusing her of instigating the murder at the hand of Ralph Capron (the previously mentioned bondsman) who plunged the knife into the heart of his victim.[23]

Whilst Eustace entered upon the manor following his father’s death, his tenure was short-lived as in 1284, John de Folville (Eustace’s younger brother) reconfirmed the five shillings in rent to the priory of Nuneaton previously granted by his grandfather and afterwards acknowledged by his father.[24]

The flaws in previously published pedigrees

John de Folville (son of Eustace and Juliana) died early in 1310.[25] His inquisition post-mortem records he held two knight’s fees in Ashby of the honour of Huntingdon, a capital messuage, and in demesne 80 acres of arable land, ten acres of meadow and various parcels of pasture.[26] John, his son and heir, was aged 23 years on 25 November 1309 (undoubtedly his birthday). By a fine dated 8 June 1310, the escheator was ordered to deliver seisin of the lands and tenements to John, excepting the part (usually a third) remaining to Alice, his mother, as dower.[27]

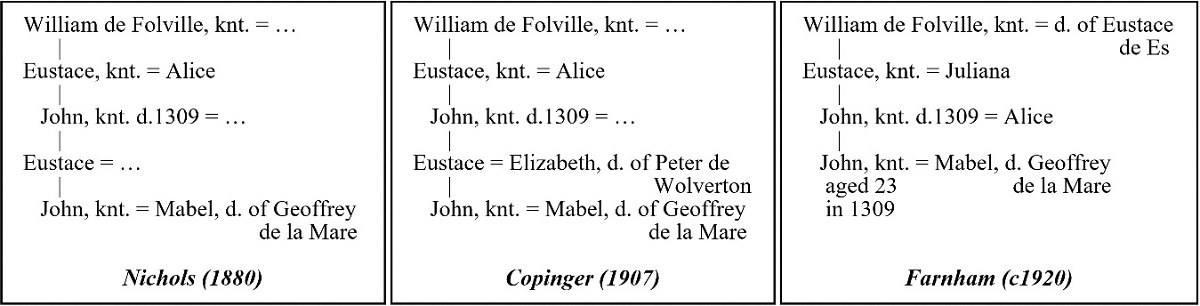

At this point, confusion manifests itself in the three primary published pedigrees by Nichols (1880), Copinger (1907) and Farnham (c1920) regarding the succession of the manor after John de Folville died in 1310.[28] The key to resolving the various discrepancies lies in the previously mentioned deed of 1343 of which a translation of the salient first part now follows.[29]

‘Know all men present and future that I, John de Folville, lord of Ashby Folville, knight, have given, granted, and by this, my present charter, confirmed to Master William de Keythorpe, parson of the church of Ashby, my manor of Teigh with appurtenances and also all lands and tenements which Dame Alice de Folville, my mother, held in dower after the death of Sir Eustace de Folville, my father, with appurtenances in Ashby Folville and Newbold and also the advowson of the church to have and to hold to the same William and his heirs from the chief lords of that fee forever by service thenceforth owed and customary...’

This was the same John de Folville who in 1314 married Mabel (the daughter of Sir Geoffrey de la Mare) as confirmed by the fact that between 1345 and 1348, John and Mabel de Folville along with Mabel’s two sisters, Joan and Maud and their respective husbands, were in legal dispute against Cecily Gerberge, the third wife of their father, Geoffrey de la Mare.[30]

If we compare relevant parts of the previously published pedigrees (Figure 7 [31]), it is clear Farnham’s version, which has stood for more than a century as the de facto Folville pedigree, incorrectly records John (who married Mabel de la Mare) as the son of John who died in 1310. Such an error suggests he did not consult the Woodford cartulary. Copinger’s account shows Mabel’s husband to be the son of Eustace and Elizabeth de Wolverton, which again is incorrect. The Eustace de Folville who married Elizabeth de Wolverton was Mabel’s brother-in-law, the leader of the Folville gang of brothers. Whilst Nichols was aware that John was the son of Eustace, the latter was not the son and heir of John who died in 1310 as that was the John aged 23 in 1309. Only Farnham correctly identifies the wife of Eustace (son of William) as Juliana, whereas the other two appear to confuse him with Sir Eustace and Dame Alice mentioned in the 1343 charter.

It appears from the evidence and chronology that after the murder of Eustace in his chamber at Ashby Folville in 1274, the eldest living son, Eustace, succeeded to the manor. However, he died sometime before 1284 leaving his widow, Dame Alice, with seven sons and a daughter all still in their minority. As a result, the next eldest brother, John, became lord of Ashby Folville, and the manor subsequently fell to his son and namesake in 1310. The most probable scenario is that the son died without issue shortly before 1314 whereupon his cousin, John (now of full age), son of the late Sir Eustace and Dame Alice, claimed the manor through right of primogeniture which he settled upon himself and his newly-wed wife, Mabel, in 1314.[32] His younger brothers, Eustace (resided at Teigh), Richard (the incumbent priest of Teigh church), Robert (resided at Newbold), Lawrence, Walter and Thomas, were the infamous band of brothers featured in the LAHS blog mentioned earlier. For more information of the Folville gang’s criminal activities, see Stones (1956).[33]

It only remains to provide the complete revised Folville pedigree taken from my article in the Genealogists’ Magazine which also shows how the manors of Ashby Folville and Teigh came into the hands of the Woodfords who created the all-important cartulary.

David J. Lewis © 2025: DaveLewis27@gmail.com

[1] British Library, Cotton, Claudius A 13, The Cartulary of John de Woodford, once of Ashby Folville, folios 232d-254, transcribed and translated by David J. Lewis (hereafter Lewis, WCart) and partly published in the transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, vol. 97 (2023), pp. 95-116.

[2] Stephen Marquis, Leicestershire’s Notorious Outlaws: The Folvilles, LAHS Blog, 2 March 2025.

[3] David J. Lewis, The Folvilles of Ashby Folville in Leicestershire, Genealogists’ Magazine (Journal of the Society of Genealogists), vol. 34:4 (Dec 2022), pp. 169-177.

[4] The Encyclopædia Britannia¸11 Ed., vol. 28 (1911), p. 299.

[6] Taken from Great Charter of King Malcolm IV in favour of Kelso Abbey, 1195 (Wikimedia Commons, public domain). Original held in the National Library of Scotland, Chartulary of Kelso Abbey, 14th century., Adv.MS.34.5.1. Archives and Manuscripts.

[7] The ‘White Ship’ sank off the French coast on 25 November 1120 and all but one of around 300 souls onboard drowned.

[8] John Nichols, The History and Antiquities of Leicestershire, in 4 volumes, London 1795-1811, (hereafter Nichols Leicestershire), vol. 3:1, pp. 20-21

[9] The Folvilles also possessed land in Ashby Parva situated around eighteen miles to the south-west.

[10] Hubert Hall (ed.), The Red Book of the Exchequer, pt. 2, London 1896, pp. 535 & 553.

[11] Nichols, Leicestershire, vol. 3:1, p. 20.

[12] Cal. Patent Rolls 1216-1225, p. 49.

[13] Cal. Close Roll 1231-1234, pp. 130 and 158.

[14] F. N. Davis, Rotuli Roberti Grosseteste Episcopi Lincolniensis 1235-53, London 1913, p. 187. See also J. Wright, The History and Antiquities of the County of Rutland, 1684, p. 123.

[15] Lewis, WCart, fo. 237. Undated but witnesses include Ralph Neville, Lord Chancellor of England between 1226 and 1238.

[16] Lewis, WCart. fo. 240.

[17] Lewis, WCart, folios 235d-236.

[18] Nichols, Leicestershire¸ vol. 3:1, p. 21.

[19] Cal. Pat. Roll 1272-1281, p. 115.

[20] The Forty-Third Annual Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, HMSO, London 1882, p. 384.

[21] The National Archives (hereafter TNA), CP 40/9, De Banco Roll (1276), m. 33d.

[22] TNA, CP 40/16, De Banco Roll (1276), m. 41d; Juliana who was the wife of Eustace de Folville vs. Aubrey de Whytlebury and Margaret, his wife, guardians of Robert Flixthorpe; also, TNA, JUST1/1223, Assize roll m. 26d; Eustace son of Eustace de Folville vs. Alice, daughter of William, son of Eustace de Folville in a plea of disseisin at Ashby Folville and TNA, JUST1/1231, Assize Roll m. 23; Alice, daughter of William de Folville vs. Eustace son of Eustace de Folville in a plea of disseisin at Teigh.

[23] TNA, CP 40/19, De Banco Roll (1277), m. 57d; John, son of Eustace de Folville, implicates Juliana who was the wife of Eustace de Folville in the murder. Ibid. 21 (1277), m. 102d; John, son of Eustace de Folville vs. Ralph Capron.

[24] TNA, Fine CP 25/1/123/34, #97 (1284).

[25] TNA, Fine CP 241/66/51, John de Folville, Alice and son John vs. Agnes de Flixthorpe, debt 22 Jan 1310. This confirms John de Folville remained alive into 1310 and did not die in 1309 as per Nichols et al.

[26] Cal. Inq. p.m., vol. 5, p. 97 (19 Jun 1310).

[27] Cal. Fine Rolls 1307-1319, p. 65 (8 Jun 1310).

[28] Nichols, Leicestershire, vol. 3:1, p. 23; W. A. Copinger (ed.), History and Records of the Smith-Carington Family, London 1907 (hereafter Copinger), p. 165; G. Farnham & A. H. Thompson, The Manors of Allexton, Appleby and Ashby Folville (hereafter Farnham), p. 475 (Transactions of the Leics. Arch. & Hist. Soc., vol. 11, 1913-20).

[29] Lewis, WCart, folios 243-243d.

[30] TNA, SC 8/192/9645, SC 197/9825A/B, SC 8/194/9682; see also Cal. Close Rolls 1346-1349, p. 525 (1348), Enrolment of release by John de Folville to Geoffrey de la Mare and Cecily de Gerberge.

[31] These have been distilled from the original published pedigrees.

[32] Lewis, WCart, folios 233d-234d.

[33] E. L. G. Stones, The Folvilles of Ashby Folville, Leicestershire, and their associates in crime, 1326-1347, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 1957.

The Folville arms: party per fess, argent & or, a cross moline gules. Recreated by David J. Lewis (2025)