Sunday 12 January 2025

Farming During The Later Bronze Age - Part 2 Animal Husbandry

LAHS Member Stuart Evans considers the Bronze Age movement of animals between the Fenlands and the Leicestershire river valleys.

Introduction

In the last blog, I considered Later Bronze Age (1500 BC to 700 BC) field systems and pit alignments, their origins and distribution. In this blog, I will look at how Bronze Age animal husbandry developed alongside the river Welland at the Fen edge and its interaction with Leicestershire's more ephemeral Bronze Age landscape described in the last blog.

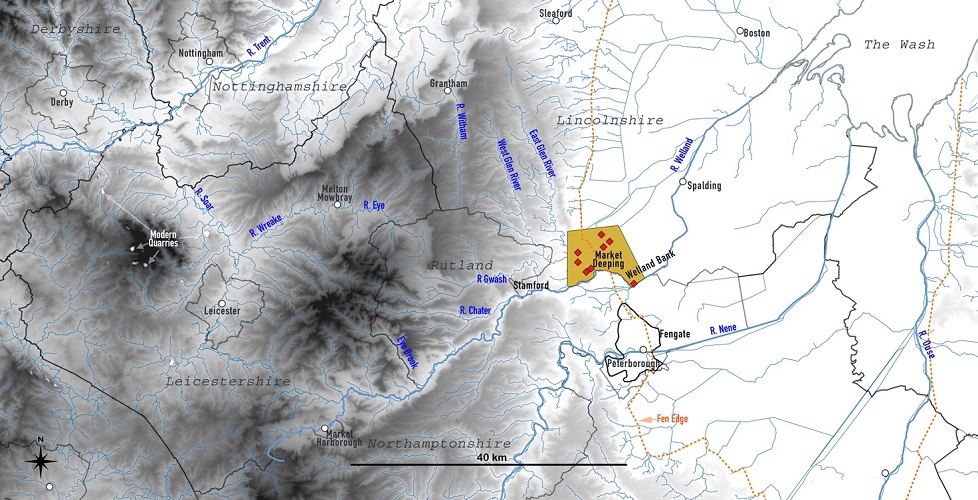

The Bronze Age field systems on the banks of the Welland in Lincolnshire were extensive - in West Deeping one system extended over 300 hectares (HER MLI83500) and eight excavations in this area have identified other field systems (Figure 1). At this point, the river Welland is about 10km north of the river Nene where the extensive Bronze Age field systems around Fengate have also been well documented (Pryor 2001).

Francis Pryor presented evidence estimating the size of the Bronze Age livestock populations in these Fen edge fields (Pryor 1998). It is thought the field systems around Market Deeping accommodated large herds of cattle and south of the river, large flocks of sheep.

This blog will use husbandry principles to consider how such intensive livestock rearing might have been carried out in the Bronze Age and how this may have influenced the development of farming further west in Leicestershire, Rutland, and Northamptonshire.

Unfortunately, the preservation of bone in the Leicestershire soils is poor, which has limited the detailed study of early animal husbandry in the county (Albarella 2019).

Bronze Age Animal Husbandry

The Bronze Age sheep were smaller than modern breeds, similar to the brown fleeced Soay sheep (Figure 2) and the available evidence indicates they were kept for both meat and wool production (Haughton et al. 2021). The Bronze Age cattle were also smaller than modern-day animals, similar to the Kerry or Dexter breed of cattle today (Figure 3). These cattle were just over a meter in height at the shoulder and age profiles of animal bones indicate that cattle were grown for a combination of purposes - milk, traction, as well as hides and meat, see Chowne et al. 2001 (Iles, page 79).

These cloven-hooved animals thrived on vast quantities of herbage. They generally need at least 2% of their body weight as herbage dry matter daily. The type of herbage they could eat would have been diverse - grasses, weeds, leaves, the bark of trees, and in some coastal areas, seaweed (Figure 4). They also need substantial volumes of water, at the extreme a lactating cow requires up to 50 litres of water a day, although non-lactating cattle only require half of this volume. Hence the large numbers of water holes found in and around the field systems.

These large quantities of herbage and water determine the husbandry practices that might have been used. In the summer, keeping large numbers of livestock was relatively easy, as grazed pastures constantly regrow. Keeping livestock becomes more difficult in the autumn when the grass stops growing and the summer meadows become waterlogged and unsuitable for grazing, limiting the food supply.

In the winter months, two strategies can be used for livestock husbandry. The first strategy is to gather hay in the summer to feed the animals in the winter. Each head of cattle requires at least one ton of hay for the winter, and sheep about a quarter of this, although the cows and ewes are likely to be pregnant and require more than this maintenance level of diet. The second strategy is extensive grazing on ungrazed, well-drained pastures, moving the herd/flock of animals, as the pastures become overgrazed, onto fresh pastures (Figure 5).

The Conundrum of Middle Bronze Age Hay

The mechanical process of cutting grass to make hay requires sharp blades and considerable force (compared to the force required to cut cereal straw). Modern machinery makes this look easy work, but cutting even small quantities of grass by hand is laborious. Before the Roman era, the only grass-cutting tools were sickles.

Bronze sickles have been found on the Continent but are relatively rare in Britain (Ballantyne et al 2024 see Uckelmann et al page 875). None have been found in Leicestershire and those that have been found at the Fen edge have been dated to the late Bronze Age (800 BC) and are thought to have been used for cutting reeds and withies. If they were not using Bronze sickles what were they using?

Flint sickles have been found and these may have been used for haymaking (Figure 6). Generally, these artefacts are usually dated earlier than the middle Bronze Age although there is considerable evidence of Later Bronze Age flint use (Ballin 2016). These lithic implements would have been fine for providing hay for small numbers of stock to supplement the winter grazing but the practicality of using this style of device to cut the huge volumes of grass required for large numbers of livestock is questionable.

In the absence of evidence of large-scale hay production, we have to conclude that they most probably used extensive winter grazing for the more intensive livestock production.

Intensive Livestock Husbandry and Winter Grazing

An important feature required for winter grazing is well-drained soil. Drainage is vital for keeping livestock on grassland over winter as the cloven hooves, particularly cattle, quickly turn undrained grassland into a quagmire, but this problem is manageable on well-drained soils at lower stocking levels. This is why the Fen edge was so critical to the intensive rearing of livestock - the soils were brown earth over well-drained gravel subsoils (Pryor 2001 see French page 400), highly suited to winter grazing.

In the autumn, the livestock would have been moved from extensive summer grazing on the Fen to the more restricted but well-drained soils of the Fen edge. This was fine in the earlier Bronze Age when the livestock numbers were low, but it presented significant problems as the population of animals grew. The pressure on these lands would have been such that organisation of the land would have become necessary to manage the animals and maintain the pastures throughout the winter. Communities built field systems with ditches not just to divide and share the land but to ensure the pastures were well-drained and grazed sequentially.

As livestock numbers increased the animals would have exceeded the capacity of the Fen edge to provide fodder in the winter, even in a highly organised landscape. This would require the autumn sorting of livestock and the culling or exchange of animals with communities away from the Fen, probably the more ephemeral Bronze Age communities to the north and west in Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Lincolnshire. The livestock sorting systems have been found in these Fenland fields and Pryor explains how they might have been used (Pryor 1996). In the century before 1100 BC the farming of livestock in these Fen edge systems was at its maximum and probably interacted with the less intense farming systems to the west to disperse animals in the winter.

Climate Change and Adaption by Moving West

Around 1100 BC, Western Europe experienced a significant change in climate. Evidence shows that it became wetter and cooler with a rise in sea levels, although the exact timing is a matter for debate (Brown 2008). This profoundly affected the low-lying Fenlands; the northern Fenlands became salt marshes, and the southern Fenlands became predominantly freshwater marshlands. There is no evidence that this was a sudden change, but it probably happened over decades - gradually, summer grazing and some of the lower-lying winter grazing was lost, and to maintain the intensity of production, the population needed to adapt its husbandry practice.

A system of seasonal grazing (transhumance) probably developed moving animals westward down the river valleys to the grazing in Leicestershire, Rutland and Northamptonshire probably interacting with the communities already established in these locations. For those communities North of the Welland, this would have used the river meadows down the Welland, in Rutland and south Leicestershire, probably up the Chater and Gwash rivers, and then back to the Fen edge for the winter.

However, the use of the field systems at the Fen edge started to decline. After a peak use in the latter part of the second millennium BC, there was a distinct decline after 1000 BC (Mason 2019, Murrell 2007, and Hatton 2019 ). The ditches silted up in the early centuries of the first millennium BC, and the landscape became more disordered (Pryor 2001). However, the settlements remained - there is evidence from Welland Bank of continued occupation (Lane et al 1996) and further south around Flag Fen (Ballantyne et al. 2024). The Fen edge communities seemed to have remained, but the field systems fell out of use. Did intensive livestock farming move westward in this late Bronze Age?

Pit Alignments

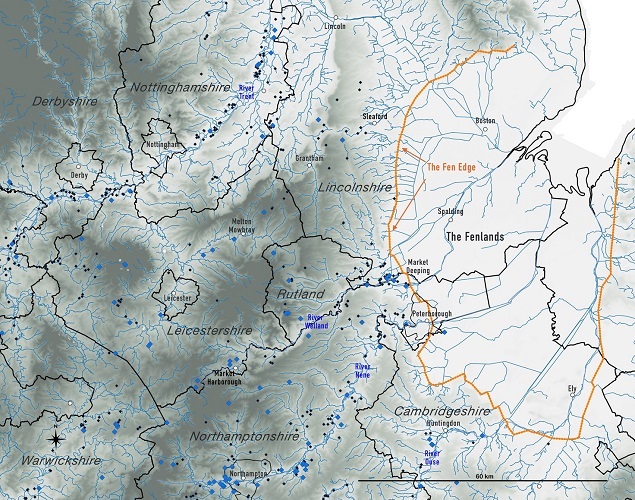

It was at this time that the pit alignments started to appear. Between 1000 BC and 500 BC, hundreds of these alignments were formed along the river meadows of the Midlands (Figure 7). Although there is still debate about the role of the pit alignment (Simmonds et al 2022), the consensus is that these earthworks were used as territorial markers. These alignments were probably indicating a demand for grazing lands and a need to mark differing communities' territories.

The value of such a permeable barrier is questionable, but shepherds and graziers who continually watched over their valuable animals would keep them within their lands. The pit alignments allowed flexible use of the land, allowing more confined grazing in the spring and summer when the herbage growth is at its maximum but in the autumn, it would allow passage through these valleys to the better-drained winter pastures. If the valleys flooded in the winter, these territorial markers would still be present in the springtime.

The pit alignments along the Nene, Welland and Trent valleys (Knight 2004) were particularly dense and it is very noticeable how these spread up into the well-drained headwaters of these rivers (Figure 7) including the Soar, Wreake/Eye, Sence and Mease rivers in Leicestershire. The absence of these alignments in the poorly drained heavy clay lands of Leicestershire and Northamptonshire is very noticeable. The wider valleys of the main rivers provided excellent summer grazing, and the tributaries and headwaters would have provided well-drained, extensive winter grazing.

It might be argued that these areas were forested but cattle and sheep, along with their cloven-hooves, are very effective at clearing wooded landscapes with little help from man. Intensive grazing of such landscapes would have denuded them of tree cover (Figure 8) (Armstrong et al. 2003). Pollen evidence has shown that significant areas in the Soar and Nene valleys were deforested in this late Bronze Age and early Iron Age period (Brown 1999). The main Trent Valley is by its very nature more complex but there are significant signs of deforestation in the first half of the first millennium BC (Haselgrove and Moore 2006 see Knight page 190).

Conclusion

In the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, much of the landscape of Leicestershire was forested but throughout the later Bronze Age, forest clearance accelerated, particularly in the river valleys. In the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, numerous pit alignments were constructed along the rich grazing lands in these valleys.

These earthworks were probably dividing the lands of a seasonal animal husbandry moving from the Fen edge interacting with the existing Bronze Age population in the county. There is little evidence to indicate exactly how these two communities settled together but certainly, by the middle of the 1st millennium BC, the population of Leicestershire was growing rapidly with an economy based on livestock farming as illustrated by Beamish et al 2008, Finn et al 2011 and Simmonds et al 2021.

References

Text underlined and in bold type is hyperlinked directly to the reference or web-based information.

Please see also Part 1 of this article, which focuses on the two types of later Bronze Age land division-Field Systems and Pit Alignments, and the relationship between them.

Correspondence - stuartevans4@icloud.com

A Soay Sheep in early summer moulting its fleece. Photo by Stuart Evans (2024)