Sunday 3 November 2024

Farming During The Later Bronze Age - Part 1 Land Division

LAHS Member Stuart Evans, assesses the context and use of pit alignments and field systems in Bronze Age Leicestershire.

This blog compares two very different forms of land division in the Later Bronze Age - Field Systems and Pit Alignments. The discussion considers the relationship between these two types of land division.

Introduction

In Britain, the farming of domestic animals and the growing of cereal crops started around 4000 BC, the early Neolithic period. This continued throughout the subsequent 2500 years as a subsistence agriculture producing food to feed the family and the local community (Cummins 2017). Small-scale exchange of goods undoubtedly occurred and there is evidence of sharing, but significant formalised trade is absent.

From the middle of the second millennium BC, this subsistence agriculture changed and became more organised, productive and incorporated goods exchange. This in turn led to the development of an economy with a maritime element with increasing exchange of goods with communities on the Atlantic border of Europe. This changing economy was originally described by Rowlands (1980 pp 15 - 56) and the concept was developed by Yates (2007) who advocated a political economy, based on the intensification of agricultural production in the south of England. This increased production manifested itself archaeologically as a land division into fields.

Field systems were not the only method used to divide the landscape - a completely different form of land division known as pit alignment has also been found. These enigmatic features were developed later in the Bronze Age and the early Iron Age. They do not seem to represent a barrier as in the smaller field divisions but most now think these widespread features delineate territorial boundaries.

Two very different systems but they both divide the land - with what purpose?

Bronze Age Field Systems1

Since the 1970s, a significant number of developer-funded excavations have exposed patterns of Bronze Age fields in wide areas of the lowland landscape in England. The fields themselves are archaeologically invisible, but the networks of ditches that outline the small fields, trackways and sometimes settlements can be found by excavation. For example, during the construction of Terminal 5 at Heathrow Airport (Figure 1) an extensive system of Bronze Age fields was discovered (Lewis J et al 2010)2.

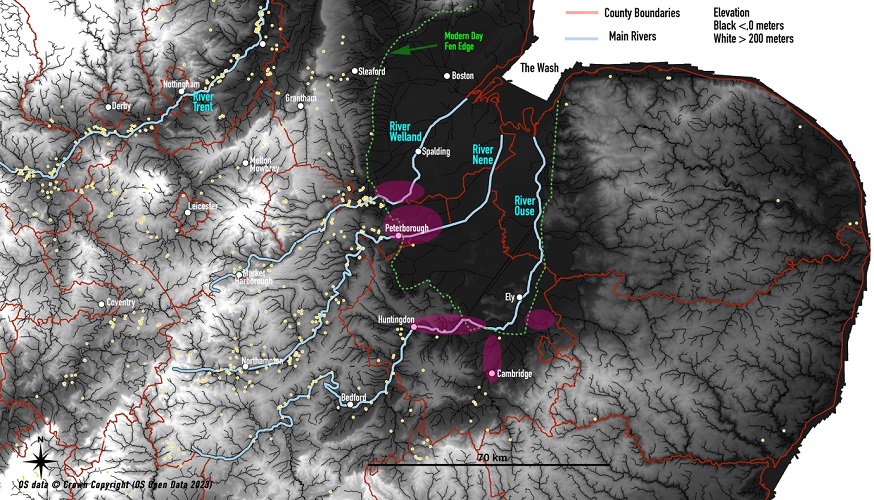

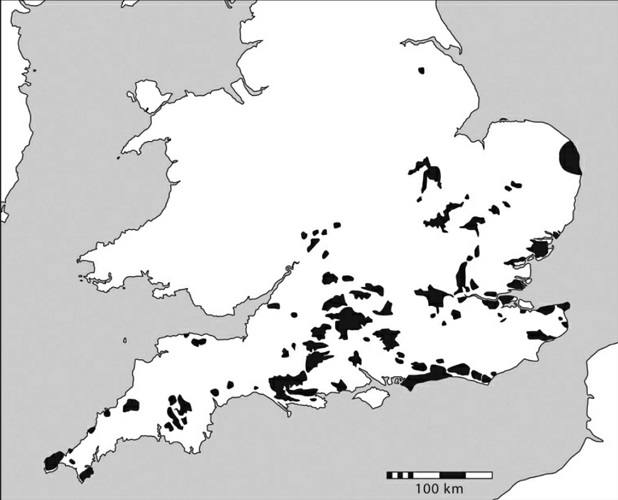

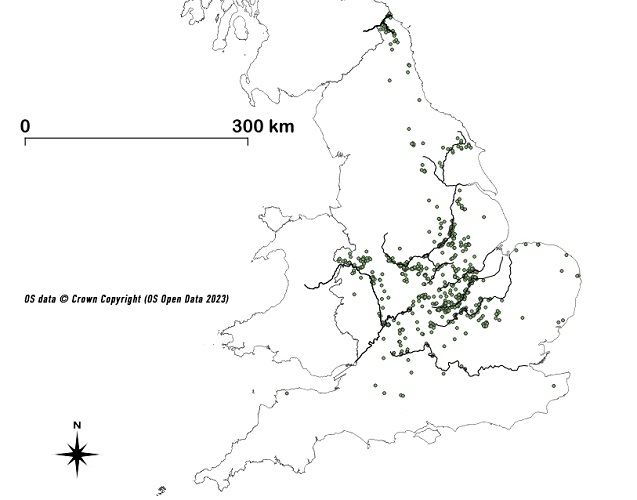

These lowland Bronze Age field systems were concentrated in the south and east of Britain (Figure 2), particularly along the south coast from Kent to Cornwall and on either side of the Thames estuary extending up the river beyond Oxford. There were also large concentrations along the Fen edges around the major rivers of the Wash, extending into South Lincolnshire. They were not evenly spread across the south of the country but seem to be in enclaves.

Many of these field systems were outside of domestic settings and the ditches usually had few artefacts associated with them. This has frequently made it difficult to date the features with any degree of accuracy - a problem that plagues the study of boundaries. Most of the field systems are estimated to have started to be formed early in the second millennium BC and they appear to have fallen into disuse around 800 BC Yates 2007 (page 112) and fields do not reappear until the Romano-British period. The field systems in the fenlands show a peak use in the latter part of the second millennium BC with a distinct decline after 1000 BC (Mason 2019, Murrell 2007 and Hatton 2019 ).

These enclaves of field systems were associated with higher concentrations of metal artefacts found within the landscape, particularly in rivers. This is interpreted as the wealth generated in these areas as a result of metal exchange for agricultural products either within the country or with northern Europe (Bradley 2019). Many of the enclaves are located at access points for European contact and Earle et al 2015 describe the potential for such exchange to occur and be exploited by those who control these access points generating wealth.

Field Systems in Leicestershire3

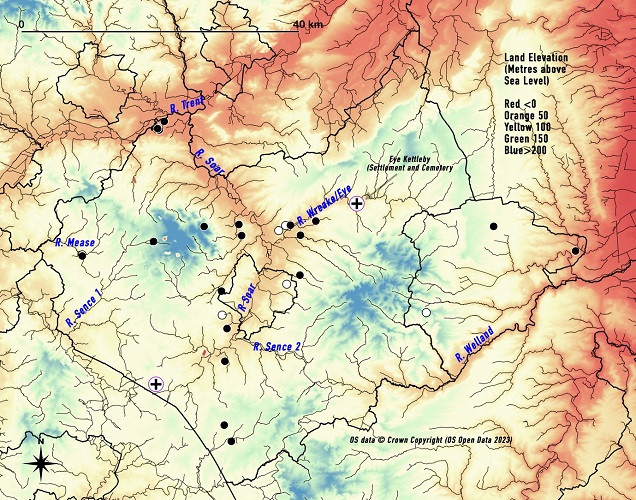

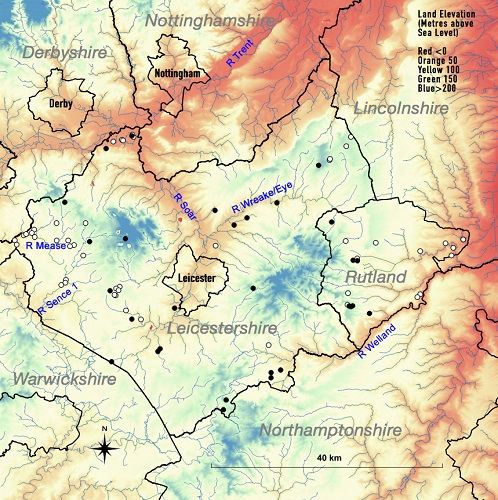

Both Yates (2007) and Bradley (2019) remarked on how abruptly the evidence of field systems stopped at the river Welland at the southern border of modern-day Leicestershire. They both state that this is due to the sparsity of Bronze Age presence in the county. However, the recent evidence does not support this argument (Willis, section 2.1.4, 2022). The density of Bronze Age activity in Leicestershire is certainly less than in the enclaves of field systems in the South but areas of the county’s landscape do have very significant evidence of Middle and Late Bronze Age settlement, particularly around Leicester and the Wreake/Eye Valley (Figure 3). This includes one of the most significant Bronze Age cemeteries found in Britain at Eye Kettleby and the Bronze Age hill enclosure at Beacon Hill - although the latter has not been fully excavated. The Bronze Age features in Leicestershire seem to be more ephemeral and dispersed.

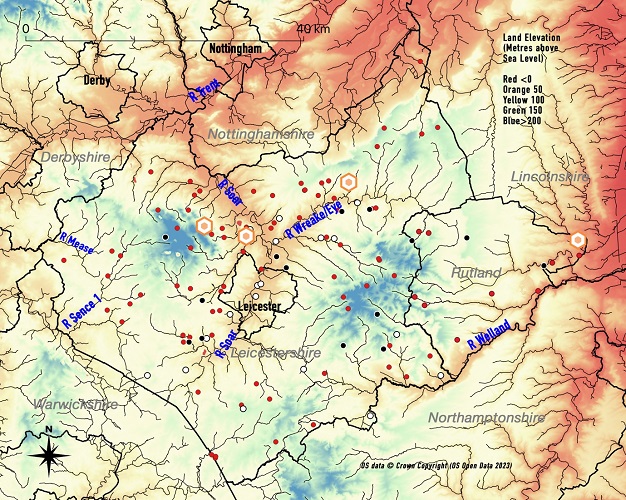

The Middle and Late Bronze Age metalwork artefacts found in Leicestershire also indicate significant activity. Metalwork has been recorded by both the Historic Environment Record (HER) and the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS). These finds again are concentrated, although not exclusively so, around Leicester and the Wreake/Eye Valley (Figure 4). These include three Late Bronze Age hoards found in the area north of Leicester. - Welby (HER MLE6366) (Figure 5), Beacon Hill (HER MLE1132) and Rothley (PAS LEIC-A6BB51). A hoard was also found in Rutland at Essendine (HER MLE6412).

There may be no field systems in Leicestershire but, contrary to the statements of Bradley and Yates, there is significant evidence of Bronze Age activity in the county.

Pit Alignments

The pit alignment is exactly what it says - a line of pits, usually extending hundreds of meters across the landscape. The pits are usually oval or sub-rectangular in shape, 1m or more across with a short causeway between the pits. The depth of the pit can be between 0.5 and 1.5m. Most are featureless but infrequently, signs of posts or stones have been found within the pits. Alignments were initially identified from crop marks, but as more extensive excavation techniques have been developed entire alignments have been investigated (figure 6).

As with field systems, they have very few artefacts within them and it is difficult to establish the dates as to when many were constructed. One exception is a pit alignment found at Eye Kettleby, dated to around 1000 BC with a degree of certainty (Finn et al 2011). Estimates of dates for most alignments indicate construction in the first half of the first millennium BC.

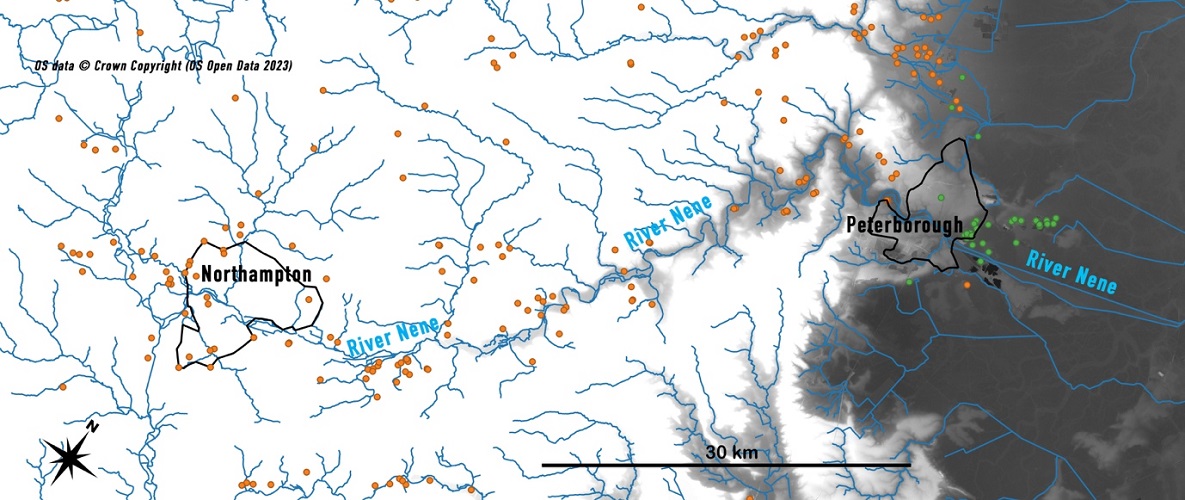

The locations of pit alignments recorded3 were plotted (Figure 7) and the map demonstrates two aspects of interest. The first is that they are absent from the south of England, occurring mainly in areas without field systems. Comparing Figures 1 and 7 you can see the field systems and pit alignments are predominantly in two distinct areas. This is particularly noticeable along the river Nene where around Peterborough there are dense field systems but as the river winds further west, the river valley is rich with pit alignments along its length (Figure 8). These alignments seem to get denser towards the source of the river around Northampton.

The second interesting feature is that pit alignments are strongly associated with the rivers of the Midlands and North, and are even as far north as the river Tweed on the Scottish Borders. They are particularly concentrated in the upper reaches of the rivers in the various tributaries. The River Severn exemplifies this feature with many pit alignments alongside the tributaries of the river in the Welsh Marches (Wigley 2006 in Pope et al 2006 page 119).

Pit Alignments in Leicestershire

Whilst there are no field systems in Leicestershire, there are numerous pit alignments. The HER records crop marks of over 50 alignments in Leicestershire of which 28 have been excavated or partially excavated (Figure 9) - examples are at Bardon Hill (Mustchin et al. 2023), Ashby-De-La-Zouch (Simmonds et al 2022) and Enderby (Kipling et al 2019). The absence of dateable evidence within the pits makes the direct assigning of dates to these pit alignments difficult. For example, the excavation of 128 pits at Bardon Hill yielded no primary dateable evidence and the only dateable item was a piece of charcoal dated between 768 and 469 BC (Mustchin et al 2023). Sometimes pottery has been found but the sherds are predominantly undecorated and cannot be assigned to a more definite period than Bronze/Iron Age (Willis 2001). Most reports are equivocal about assigning dates.

Similar to elsewhere, the pit alignments in Leicestershire are associated with tributaries of the main rivers. To the west of the county, these are associated with the Rivers Sence5 and Mease running west into the Trent and also the Thurlaston Brook running east into the Soar. To the south of the county, they are related to the River Welland and its tributaries, and to the east the River Wreake/Eye and its tributaries. Most are located within a few hundred metres of the water course and are in general 10 to 20 meters above the river water levels. Only 1 (Lockington) of the 28 excavated alignments in Leicestershire is near the modern river level.

Discussion

These two types of land division are very different in design and geographic location. The layout of the field systems shows the intensity of land use in enclaves of southern England from about 1500 BC. In contrast, the pit alignments were constructed later (From 1000 BC) and are more widespread along the upper reaches of the river systems, indicative of land being used in a more dispersed manner in these locations.

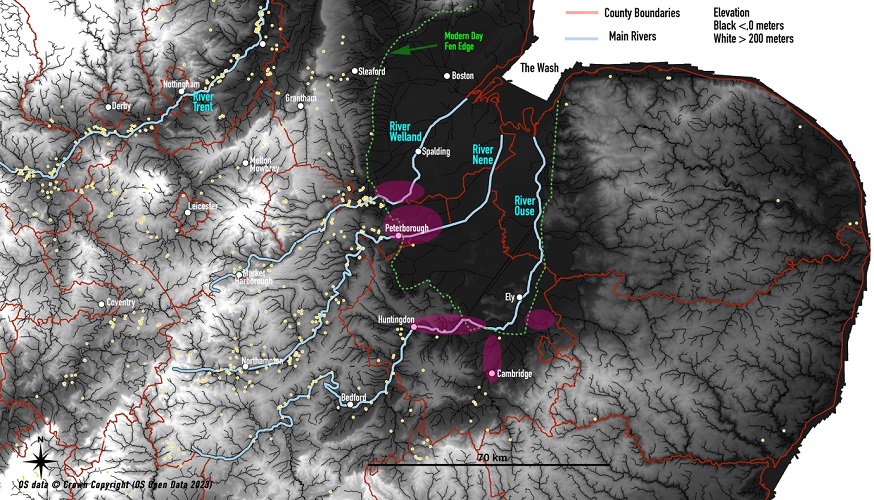

Leicestershire, with no field systems, and significant numbers of pit alignments falls into the second of these geographic areas. The environmental assessment of the Leicestershire landscape at this time is one of open grassland along the river valleys and their tributaries supporting the grazing of animals (Brown 1999, Beamish et al 2008). Cereals were grown but in small quantities, sufficient to support the immediate community (Monckton 2004, Page 154). This pastoral environment in Leicestershire coexisted adjacent to the more intensive agriculture indicated by field systems found in the neighbouring areas of North-East Northamptonshire and South Lincolnshire (Figure 10). In Leicestershire, the agricultural environment seems to emerge throughout this period, with tensions on land ownership only being evident from the beginning of the first millennium BC and the marking of territories with pit alignments.

This raises a number of questions - if, contrary to the assertions of Bradley and Yates, there was a significant population in Leicestershire in the middle Bronze Age, why did the field systems stop at the southern border of the county? And why did the apparently more intensive and productive field systems decline and was that decline linked to the growth of the pit alignments?

Please see also part 2 of this article, which considers how knowledge of animal husbandry might answer these two questions.

Notes

- The terminology describing these field systems is varied, earlier texts called them “Celtic field systems” but this confused Bronze Age systems with later Roman/British fields. The terms coaxial or rectilinear field systems are also sometimes used.

- Lewis, J., Leivers, M., Brown, L., Smith, A., Cramp, K., Mepham, L. and Phillpotts, C. (2010). Landscape Evolution in the Middle Thames Valley: Heathrow Terminal 5 Excavations, Vol. 2. Oxford / Salisbury: Framework Archaeology.

- For this study, Leicestershire reflects the structure of the databases used and includes Leicestershire County, Leicester City and the Unitary Authority of Rutland.

- The recording of pit alignments in the HER is variable. Cropmarks were only used as evidence if recorded twice by more than one observer over a period of years. Records were only considered if the alignment had more than 7 pits aligned and extended over at least 25 meters.

- The Ordnance Survey shows two River Sences’ in Leicestershire - one in the west of the county arising below Bardon Hill and flowing into the River Anker - the second rises near Billesdon and runs through Great Glen to the Soar.

References and Supporting Information

Text underlined and in bold type is hyperlinked directly to the reference or web-based information.

Copyright

LIDAR Data was downloaded from the DEFRA survey and is subject to the Open Government Licence v3.

Correspondence - stuartevans4@icloud.com

A greyscale LIDAR elevation image of the East of England. This shows the relationship between the Field system enclaves of the Fens (Purple areas), the recorded pit alignments (yellow circles) and the river systems. LIDAR Data downloaded from DEFRA Survey