Sunday 17 November 2024

Anglo-Saxon Leicestershire. The exceptional available evidence

LAHS Member Bob Trubshaw reviews the abundant evidence now available from archaeological, iconographical, place-name and landscape studies.

Leicestershire has more evidence for Anglo-Saxon activities than almost all other English counties. But only some of that evidence is archaeological.

When I moved back to Leicestershire in 1986 the available information on Anglo-Saxon Leicestershire was, shall we say, minimal. In the following forty years this has changed almost out of recognition. In part this is because of archaeological discoveries – with significant contributions by amateurs as well as professionals.

At least as important, Leicestershire and Rutland now have countywide publications on major and minor place-names. Only more recently has one other county, Dorset, received such complete study. Most counties only have studies of the major place-names and patchy publications on specific hundreds.

In addition, there have been some useful academic papers on aspects of the documented history. Two offer especially rewarding insights.

Most of what we knew back in the 1970s was almost entirely about how dead Anglo-Saxons were buried – either as inhumations or as cremations. Settlement sites were almost unknown.

Starting in the late 1970s Peter Liddle’s community archaeology fieldwalking projects throughout Leicestershire began to shed considerable light on the pre-nucleation dispersed farmsteads, especially in the Medbourne area and the Langtons (walked by Paul Bowman).

Since the mid-1990s developer-funded excavations have revealed both minor and major settlement sites for most centuries during the Anglo-Saxon era. The biggest by far is at least 35 Anglo-Saxon houses at Eye Kettleby. As part of the recently published report of those excavations Gavin Speed compiled an up-to-date overview of mid-fifth century to mid-seventh century Leicestershire (Speed and Finn 2024 Ch. 5&6, see also Gavin’s recent LAHS blog) which is itself an important resource.

In common with other parts of England, the introduction of the Portable Antiquities Scheme in 1997 opened the floodgates for the proper recording of finds. The online PAS database is itself a treasure trove of information, especially when combined with the Historic Environment Records. Leicestershire was lucky in having Wendy Scott as the PAS Finds Liaison Officer from 2003 until 2019. This role is now fulfilled by Megan Harvey because Wendy went off to do a PhD on 11th century coinage. During her time at PAS, Wendy became especially interested in fifth century Scandinavian amulets known as bracteates. She has published papers on two identical ones found in Leicestershire.

There is another aspect of the material culture of Anglo-Saxon Leicestershire which less often ends up in museums. I’m referring to the substantial number of Anglo-Saxon stone carvings. David Parsons published an overview in 1996, and the Leicestershire volume of the Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Sculpture is close to publication. One of the new insights will be knowing with some certainty where the stone was quarried, as this will indicate trade routes and maybe secular and ecclesiastic patronage.

Mostly these carvings are fragments of cross-shafts and grave covers, often incorporated into the fabric of churches – as with examples at Market Overton and Harston. But two near-complete cross fragments stand in the churchyards at Rothley and Sproxton. The Rothley one is missing the wheel cross originally on the top. And the Sproxton one is missing the lower part. Although now in Sproxton churchyard, most likely it was originally on the boundary with the adjoining parish of Buckminster. Other cross shafts, such as those at Asfordby and Foxton, now stand inside the church.

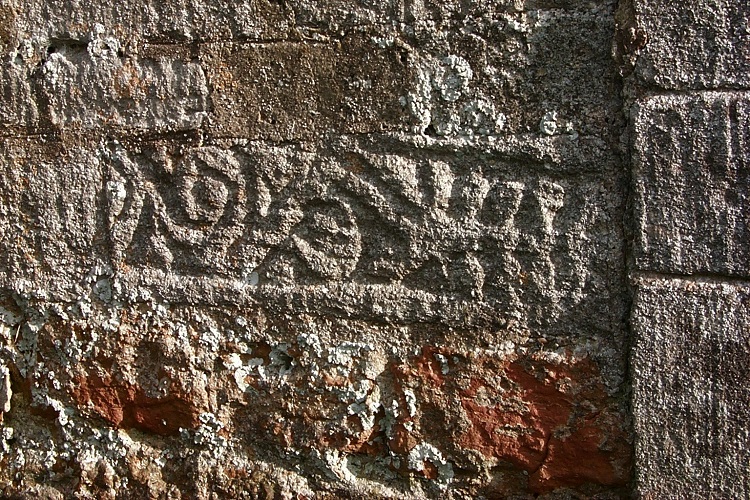

Leicestershire is also home to one of the most important surviving collections of eighth century carvings, the remarkable friezes now inside Breedon church but originally on the outside of a much older building. About two hundred years later these apostles and an archangel – most likely Archangel Gabriel – were carved. At Breedon there’s also a collection of cross shaft fragments which incorporate both Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian motifs.

The iconography on these carvings allows insights in slowly-evolving ‘worldviews’ within early Christianity.

Exciting and informative as all the archaeological discoveries and material culture are, our understanding of Anglo-Saxon Leicestershire has also benefited from important non-archaeological studies. Even though there is little surviving documentary evidence as, thanks to Viking depredations, Leicestershire has few Anglo-Saxon charters or contemporary historical sources. For the period before the Norman Conquest even Michael Wood’s work at Kibworth for the 2010 TV series Story of England relied on using archaeology, landscape, language and DNA analysis.

The near absence of documentary evidence is not a total barrier. The most exceptional non-archaeological research is Barrie Cox’s lifetime of work studying the place-names of Leicestershire and Rutland. Not just the major settlement names but all the minor names, such as field names and pub names, as well. Few, if any, counties have such a complete resource.

Even before Barrie’s work was published Jill Bourn had shown that the Scandinavian settlement in Leicestershire – especially in Framland Hundred, but almost none in Rutland – is preserved in the place-name evidence. Rebecca Gregory, based at Nottingham University, continues to research the Vikings in the East Midlands using place-names as a key part of her approach.

.jpg)

Place-names offer both simple and sophisticated insights. Among the simplest are the Waltons and the Burtons. Walton is from wahl tun which means the settlement of the British-speaking slaves. So clearly from the early phases of Anglo-Saxon settlement, and suggesting something akin to apartheid-era South African townships and segregation.

Burtons are several centuries later, during the reign of King Alfred – most probably the 870s – and were deliberately-planted garrison settlements to help defend against Viking raids. The three Burtons in Leicestershire – Burton Overy, Burton Lazars and Burton on the Wolds – are strategically sited to protect the royal estate centre at Great Glen, the important ‘central place’ at or near Melton Mowbray, and the crossing of the River Soar between Cotes and Loughborough which would have been of strategic military significance when defending against waterborne raiders attempting to come up the Soar and thence the Wreake and Melton Mowbray.

Other place-names require more sophisticated approaches. Graham Aldred produced a PhD on ‘worth’ names in Leicestershire and Mercia, attempting to understand why worths tend to cluster in groups close to junctions of major routes, usually of Roman origin.

A considerable amount of my own research into the Anglo-Saxons of Leicestershire also stands on the shoulders of Barrie Cox’s place-name publications. For example, the place-name element hoh (as in the various Leicestershire village of Hoton, Houghton, Hoby and Hose, and also in field names) seems to be found in parishes on the boundaries of hundreds. They are distinctively-shaped hills which, before the conversion to Christianity, might have been the location of 'boundary shrines'. I have discussed this in a free-to-download PDF.

Using a mix of surviving records and minor places names Susan Kilby has made some remarkable insights into the lifestyles of ordinary people – the peasants if you like. However, her work has so far focussed on places in Northamptonshire, Huntingdonshire and Suffolk. As yet, there has not been a similar approach within Leicestershire or Rutland.

A concise but most valuable study by David Parsons published back in 1996 identified the earliest churches – more correctly known as mynsters – in Leicestershire and Rutland. This required careful analysis of later documents. Only a few other counties – such as Wiltshire, Radnorshire, parts of Sussex and the Thames valley – have received comparable investigations.

Parsons’ paper was prepared for an innovative conference in 1991 which took a broad view of Anglo-Saxon landscapes in the East Midlands. This conference was instigated and organised by Jill Bourn who brought together archaeological approaches with art historians and others – including Ian Wilkinson who looked in detail at the geology underlying Anglo-Saxon settlements, revealing that the earliest settlements were on the best-drained soils such as sands and gravel. So far as I am aware the scope of Jill’s pioneering conference has not been emulated over thirty years later.

In 2015 Graham Jones 'revisited' Leicestershire's mynsters and identified the parochia (or pays) associated with each one. In essence these administrative areas are associated with river valleys. His research closely paralleled my entirely independent approach to the locations of such early churches, also published in 2015 as Minsters and Valleys. This also established that the earliest churches in land-locked counties (such as Leicestershire and Wiltshire) were consistently in locations ideally suited for waterborne transport. To the extent that there was one per river and one for every river.

The main surviving evidence for later Anglo-Saxon Leicestershire is so abundant that we are wont to ignore it. Most of the settlements which evolved into nucleated villages during the tenth and eleventh centuries still exist as modern-day villages. Which means most of our roads and lanes came into existence about the same time.

So, by combining fairly well-understood national trends with the exceptionally good archaeological, iconographical and toponymical resources for the county the stage is set for unique insights. Especially ones which look across the boundaries of the different disciplines and combine, for example, material culture with geology, topography and place-name studies. Just as Jill Bourn pioneered back in 1991 but now with the benefit of vastly more research.

Bob Trubshaw

Email: bobtrubs@indigogroup.co.uk

This article is based on a video published on Bob’s youtube channel which can be accessed here. He has also completed a much longer study into Anglo-Saxon Leicestershire which is available as a pdf download.

Works and web sites cited

Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture web site. Durham University.

Portable Antiquities Scheme website

Leicestershire Historic Environment Record

Aldred, Graham, 2023, The Role and Origins of Mercian Settlements with the Place-Name Worth, BAR.

Bourne, Jill, 2003, Understanding Leicestershire and Rutland. Place-names, Heart of Albion.

Bowman, Paul, 2004, ‘Villages and their Territories Parts I & II’ from Leicestershire Landscapes Paul Bowman and Peter Liddle (eds), LMAFG Monograph No. 1

Cox, Barrie, 1996, The Place-Names of Rutland, English Place-Name Society.

Cox, Barrie, 1998–2016, The Place-Names of Leicestershire (7 volumes), English Place-Name Society.

Jones, Graham, 2015 [2016], 'The origins of Leicestershire: churches, territories, and landscape', in K. Elkin (ed), Medieval Leicestershire: Recent research in the medieval archaeology of Leicestershire, Leicestershire Fieldworkers; revised version online at ICAC.CAT.

Kilby, Susan, 2020, Peasant Perspectives on the Medieval Landscape, University of Hertfordshire Press.

Liddle, Peter, 1985, Community Archaeology: A Fieldworker's Handbook of Organization and Techniques, Leicestershire Museums.

Parsons, David, 1996, ‘Before the parish: the church in Anglo-Saxon Leicestershire’, in J. Bourne (ed.), Anglo-Saxon Landscapes in the East Midlands, Leicestershire Museums Arts and Records Service.

Scott, Wendy, 2p15, ‘The significance of a… bracteate from the Melton Mowbray area’ in TLAHS

Speed, Gavin and Neil Finn, 2024, The Anglo-Saxon Settlement at Eye Kettleby, ULAS.

Trubshaw, Bob, 2015, Minsters and Valleys

Trubshaw, Bob, 2016 [revised 2020], Rethinking Anglo-Saxon Shrines

Wood, Michael, 2010, The Story of England, Penguin.

Background image: Anglo-Saxon Carving, Breedon on the Hill. Photo by Bob Trubshaw (2007)

Anglo-Saxon Carving, Breedon on the Hill. Photo by Bob Trubshaw (2007)