Sunday 14 April 2024

The persistence of patronage and the composition of the Anglican Clergy in the Archdeaconry of Leicester, c.1850-1903

LAHS Member Dave Fogg Postles considers the continuing influence of patronage, reviewing both who owned the rights to put forward clergy for appointment to vicarages and providing examples demonstrating what this meant in practice as to who might then be appointed.

In this short piece, I wish to remember the contribution to the county’s history by the late Gerald Rimmington, a stalwart supporter of the Society. The extract below is from my current research into the character of the Anglican clergy in the transformative period after 1850.

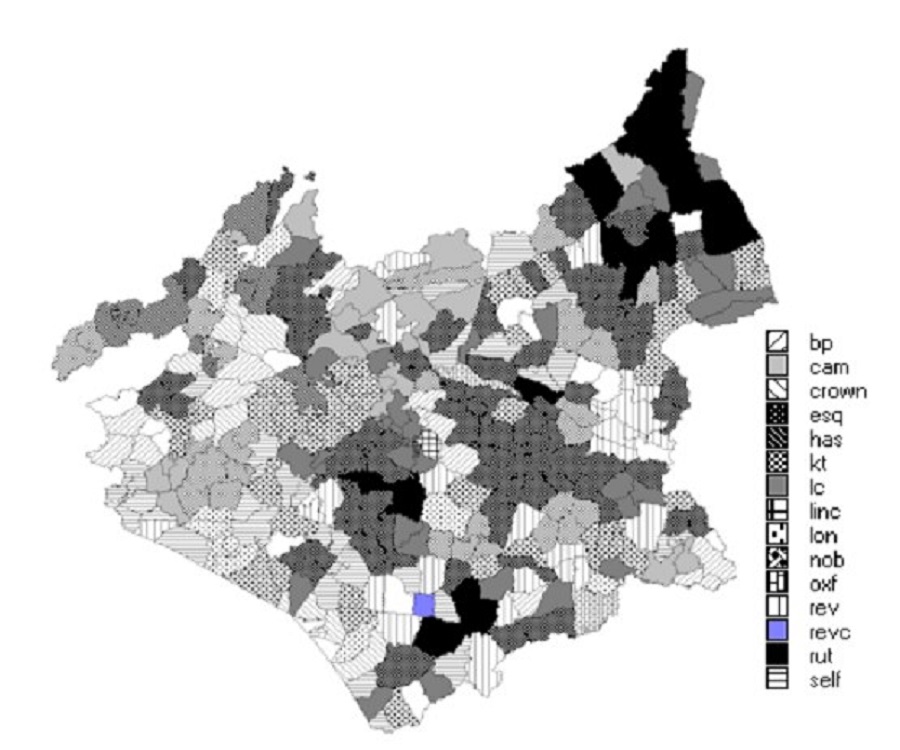

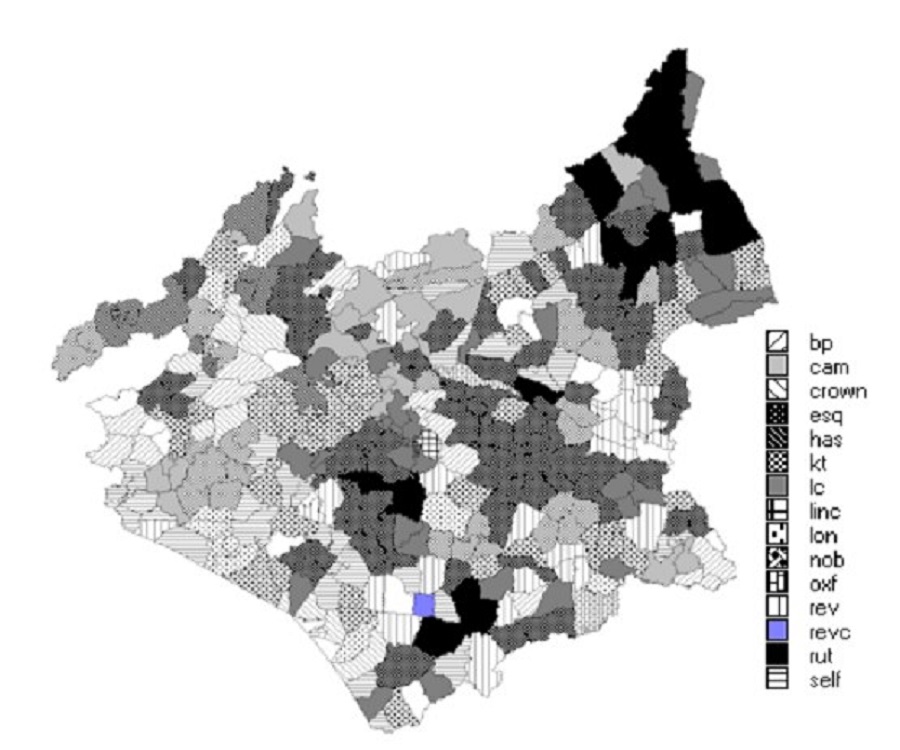

We are perhaps inured to consider that the influence of patronage in the Church of England was at its zenith in the early-modern period. Its continuity, however, was deceptive. As the Anglican authorities attempted to combat the expansion of nonconformity in the nineteenth century, its efforts were to some extent compromised by the persistence of patronage. The pattern of preferment was still dictated by the structure of patronage.1 This pattern can be best determined from the Clergy List of 1852.2 Some livings, however, seem not to be included and the data has been supplemented by Crockford’s Clerical Directory for 1860. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of patronage.

In this figure the following applies as to who the patron was for a particular living

| bp-Bishop | crown-Crown | has- Hastings Family | lc- Lord Chancellor | lon- of London | oxf-Oxford University/ College | rut - Duke of Rutland |

| cam- Cambridge College | esq- esquire | kt- Knight | linc- Dean & chapter of Lincoln | nob- nobility | rev (c)- cleric | self-rector was own patron |

In

terms of the number held by one patron (in this case, an office), the

Lord Chancellor presented to 27 livings (that is a rectory or

vicarage with its appurtenant chapelries). Next in the number of

livings appropriated to one patron was the Duke of Rutland with

sixteen. The difference was that the Rutland livings were

concentrated in the north-east of the county. They consisted mainly

of advowsons acquired by Belvoir Priory and later re-appropriated by

the Manners family. Many of these livings in the gift of the Manners

had modest income, but there were also half a dozen prizes with gross

income near to (one) or exceeding five hundred pounds. The Hastings

family had the presentation to six livings. Other nobility, each with

one or a few livings, had 28 parochial presentations. Those described

in the Clergy

List as

esquires had accumulated 44 rights of presentation. Significant among

these esquires was Thomas Frewen (1811-1870), of Cold Overton, who

was patron of four livings, including Melton Mowbray with its

numerous chapelries. Knightly families had fewer, seventeen.

Cambridge Colleges accounted for ten, with Emmanuel prominent.

The lower clergy (that is, those holding no high ecclesiastical office and designated simply reverend) themselves presented to 47 livings. In 24 livings, the rector was also patron, either by inheritance or by purchasing the right of presentation. In the other 23 instances, the patron of the living was a cleric who presented a different clergyman, not himself.

The Cambridge colleges in particular had a penchant to present their own graduates and also Fellows who were not always resident. During this time Emmanuel College presented its own fellows to the lucrative livings in Loughborough, Robert Bunch and Henry Fearon. Consecutive incumbents from Pembroke College were advanced by the college as patron to Sibson, John Cox and Thomas Page. The Fellow of Trinity College, John Echalaz, received the college’s living at Appleby Magna. To the rectory of Medbourne St John’s College promoted its own Laurence Baker.

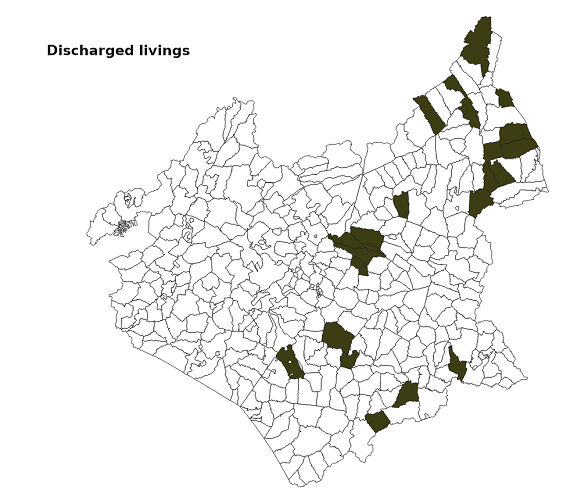

In particular, discharged rectories and vicarages (those exempt from first fruits and tenths in the past) were in the hands of colleges which proposed their own colleagues. (First fruits and tenths had been levies on the first year’s income from the livings of newly-instituted clergy). Eleven of the twenty-one were held by Cambridge colleges and five by Oxford institutions. The theological colleges, St Bees and St Aidan’s, had each acquired one. Figure 2 illustrates the location of these discharged livings where the incumbent was likely to be absent.

The

persistence of lay patronage is remarkably represented by the rectory

of Bottesford. Richard Norman, esq. (1761-1847), married Lady

Elizabeth Isabella Manners (1777-1853), the daughter of the 4th

Duke of Rutland. Their son, Frederic John (1814-1888) was preferred

to the rectory of Bottesford in the patronage of the Duke. In 1848,

Frederic espoused Lady Adeliza Elizabeth Gertrude Manners, by whom he

had issue one daughter and three sons. Their son, Robert Manners

Norman (1855-1895), in 1887 married Lilias Elizabeth Drummond, eldest

daughter of Edgar Drummond, banker and magistrate of London (in her

widowhood, she returned to the metropolis).3

Frederic

John Norman, the issue of Richard and and Lady Elizabeth, graduated

from Cambridge (Caius College) in 1838 and received the living at

Bottesford in 1846. At that time, the glebe of 700 acres could be

leased for the substantial rent, which resulted in a gross income for

the rectory of £1103 (net income £1000). From 1872, Frederic was

appointed an honorary canon of Peterborough cathedral. His son,

Robert Manners Norman, succeeded him in the rectory. Robert was

another graduate of Cambridge (but the affluent Trinity College) in

1877. He received the rectory in 1889 immediately after the death of

his father. By then, the glebe could be leased for the lesser rent of

£800 in the midst of the ‘agricultural depression’, furnishing a

gross income of £805 (net £555). Robert had previously served as

curate of Doncaster (Yorkshire W. R.) (1877-8), then Kensington

(Middlesex) (1878, where he may have encountered his future wife’s

family), subsequently as vicar of Maltby (Yorkshire W. R.) (1880-6),

and finally as curate to his father (no doubt from his father’s

income) in Bottesford (1886-9).4

.jpg)

When

Frederic died, his estate was valued at £11,631 5s 10d. Six years

later, despite the decline in the value of the rectory, Robert’s

estate was appraised at £25,421 8s 3d.5

These familial episodes divulge the continuous importance of lay

patronage for some livings. The Duke of Rutland as patron of

Bottesford ensured the preferment of relations to the living, one of

the most valuable in the county.

The Duke of Rutland had patronage of a nexus of churches in north-east Leicestershire which undoubtedly had some local influence. Indeed, Snell and Ell have demonstrated how intensive landownership, sometimes exercised through ‘estate villages’, coincided with a high degree of Anglican worship.6

An interesting example of determination by patronage was the clerical career of George Edward Bruxner. A British Subject born in St Petersburg in Imperial Russia, Bruxner matriculated at Oxford in 1832 aged nineteen. Receiving his BA in 1836 and MA in 1838, he was instituted to the rectory of Thurlaston in 1845, a comfortable living with a gross income of £440.7 There he served for just over three decades.

His route to the rectory was through patronage. In 1841, he married Anne Mary Arkwright in her parish church of Latton (Essex), the usual uxorilocal venue.8 She was the daughter of the Reverend Joseph Arkwright (1791-1864) of Mark Hall in Latton. The Mark Hall estate had been purchased in 1819 as an investment by Richard Arkwright of Willesley Castle (Derbyshire), the issue of the celebrated Arkwright. The Reverend Joseph, as sixth son, entered the clergy and received the living at Latton, a rectory.9 When the elder son, Richard, died in 1832, Joseph inherited the estate and resigned from the living, now a cleric without cure of souls. With the wider Arkwright estates, Joseph gained the patronage of Thurlaston. When the vacancy occurred at Thurlaston, Arkwright presented his son-in-law, Bruxner. (George Edward’s son, Edward Arkwright Bruxner, entered the legal profession and became a barrister at the Inner Temple).10 In 1861, George purchased from Joseph Arkwright the remainder of the term of 1,000 years in the advowson of the church with the parsonage house and the glebe of 223 acres for £4,000 (perhaps at a discount from his father-in-law, for which see above).11

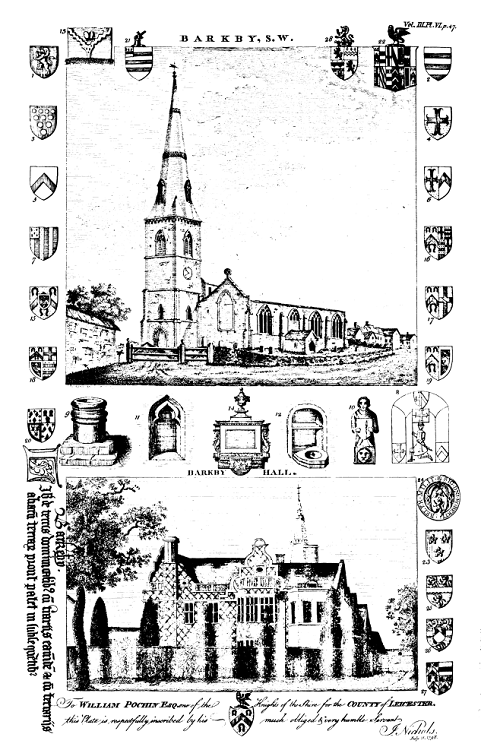

The influence of patronage obtained too in the preferments of Edward Pochin, but with different consequences perhaps. Edward Norman Pochin (1828-97) was a younger son of George and Elizabeth of Barkby Hall. His elder brother, William Anne (born 1820), inherited the estate and the patronage of livings. Edward was sent off to Eton and graduated from Cambridge (Trinity College) in 1851. His first position was curate of Burton Lazars with Welby and Sysonby between 1851 and 1856, under the patronage of Thomas Frewen esq., and perhaps at the bequest of the Pochins. From 1852, his career was sponsored by William Anne, first in the living at Thurmaston (vicarage, 1852-1856), then Sileby (1856-73) and finally the vicarage at his home seat of Barkby, which he held until his demise. William Anne possessed the patronage of all of the vicarages of Thurmaston, Sileby and Barkby. All livings provided only a modest income: Thurmaston £155; Sileby £152; and Barkby £250. The first two vicarages indeed would have qualified as poor and the final very mediocre. What was obviously important to Edward was not to accrue more wealth but to have a comfortable vicarage with his spouse and family near his original home.12 Edward did not lack for personal finances; when he died in 1897 his estate amounted to £111,261 6s 3d.13 He had not invested his funds in purchasing a high-value living.14

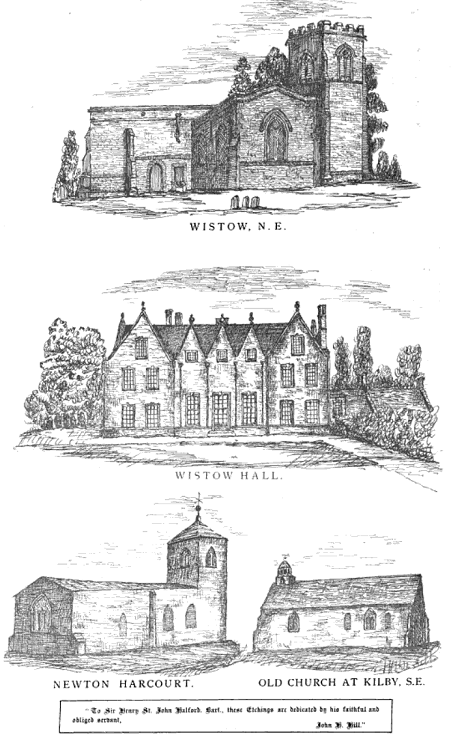

Another,

but by no means the only other, example was the Reverend (later Sir)

John Frederick Halford (1830-1896). Having graduated from Cambridge

(also the well-funded Trinity College), he was appointed to a curacy

at Cossington where he served from 1853 to 1855. After serving for

some time as curate at Wistow, he was elevated to the living as vicar

in 1867, combining the living with that at Kilby. In 1881, he assumed

the vicarage at Brixworth (Northamptonshire).15

In 1861, he was living, aged thirty and married, as curate of Wistow

with his parents at Wistow Hall.16

He was indeed a younger son of Sir Henry Halford, physician to the

King, who had purchased Wistow Hall and its estate. In later life,

after the death of his brother, John Halford inherited the title and

the estate and was interred at there in 1896, aged 67.17.18

These anecdotal references are illustrative of a wider pattern of the continuing influence of patronage on the character of the clergy in the county and archdeaconry.

Dave Fogg Postles ©(2024)

This research forms part of a larger study which is now available as an online booklet entitled Characteristics of the clergy: the Anglican experience in the late-Victorian transition in Leicestershire

References

1M. J. D. Roberts, ‘Private patronage and the Church of England, 1800-1900’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History 32 (1981), pp. 199-223; James Obelkevich, Religion and Rural Society: South Lindsey, 1825-1875 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976), pp. 112-113. In general, Alan Haig, The Victorian Clergy (Beckenham: Croom Helm, 1984).

2The Clergy List for 1852 (London: C. Cox, 1852.

3ROLLR DG36/9, p. 23 (no. 177); DE4411/2, p. 39 (no. 78); DE829/15, no. 134; TNA RG9/2349, fo. 29v.

4Crockford’s Clerical Directory 1882, p. 796; 1895, p. 981.

5National Probate Register 1889 Ma Vius-Nye p.; 1895 Naden-Rynd.

6K. D. M. Snell & Paul Ell, Rival Jerusalems: The Geography of Victorian Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 373-5 (eschewing the term ‘closed parish’).

7The National Archives HO107/2081, fo. 460V; Joseph Foster, Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford 1715-1886 A-D (London: Parker & Co., 1888), p. 180; ROLLR 7D55/1016/1-3 (presentation deed).

8Essex Record Office D/P 344/1/10, p. 2.

9TNA RG9/1065, fo. 76; for his demise, Ball’s Weekly Messenger 7 March 1864, p. 7. His estate was valued at under £400,000.

10Leicester Chronicle 27 June 1868, p. 8.

11Record Office for Leicestershire Leicester and Rutland 7D55/1273.

12ROLLR DE2579/8, pp. 22 (no. 169) and 46 (no. 363); Crockford 1870, pp. 533, 562; 1885, p. 950; TNA RG11/3155, fo. 113.

13NPR 1897 Nabb-Ryves, p. 168.

14John Nichols, The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester volume III part i (London: Nichols, 1815) between pp. 46 and 47.

15Crockford 1882, p. 461.

16TNA RG9/2254, fo. 104.

17ROLLR DE7013, p. 45 (no. 357).

18John Harwood Hill, The History of Market Harborough: with that Portion of Gartree, Leicestershire … (Leicester: Ward & Sons, 1875), between pp. 314-315 (etchings by Hill).

Distribution of Patronage within the Anglican Clergy in Leicestershire c.1852 (Dave Fogg Postles 2024)