Sunday 26 May 2024

The ‘Forgotten’ Alabaster of Burton on the Wolds

Joan Shaw and Bob Trubshaw examine the little known history of alabaster quarrying in Leicestershire.

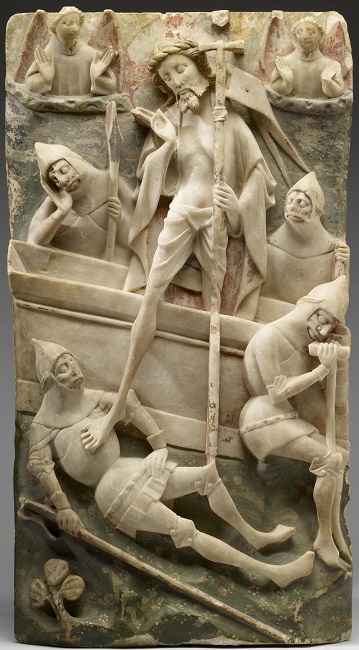

Alabaster is a fine-grained white or lightly-tinted crystalline variety of the mineral gypsum (calcium sulphate dihydrate). Although too soft to be ideal for external uses, alabaster was regarded as an optimum material for figural carvings, especially sepulchral monuments and finely-detailed religious iconography.

Alabaster is no longer quarried in Britain. However gypsum is currently extracted in vast quantities from drift mines with entrances at Barrow-upon-Soar and East Leake. Within a few decades these two mines will 'meet' underneath north Leicestershire – although separated by a geological fault which means the two mines will be offset vertically by about eighty metres. Quarries near Newark extract a low iron-content gypsum used for plaster of Paris and other speciality products, such as the sticks of 'chalk' used in classrooms. Gypsum is also still extracted at Fauld in Staffordshire, as it has been since medieval times, and quarries in Cumbria and Kent.

Historical references to quarrying can be confusing as 'alabaster pits', 'gypsum pits' and 'plaster pits' all refer to the extraction of gypsum. Some 'marl pits' also extract gypsum, typically where a layer of gypsum has partially dissolved leaving a mixture of gypsum 'boulders' separated by soils washed into the voids.

The oldest-known alabaster quarries in Britain seem to have been in the early thirteenth century at Tutbury in Staffordshire. Historical records indicate that by the middle of the fourteenth century working of alabaster had expanded from Tutbury to Chellaston. The stone from both areas was extracted and worked by skilled 'alabasterers', 'alabastermen', 'kervers' (carvers), 'imagers' and 'imagemakers' (a widely-used term for wood- and stone-carvers before the word 'sculptor' was adopted). Nottingham was famous in medieval times for the alabaster workshops making low-relief religious scenes to go behind altars and different styles of sepulchral effigies, although the Nottingham 'imagers' seemingly relocated to Burton on Trent around 1550. Other workshops existed at York and London.

Alabaster from Leicestershire

By the late sixteenth century there were more quarries. One was at Redhill near Ratcliffe on Trent. At least two more were further south in Leicestershire. These were largely unknown until Raymond State published his major study The Alabaster Carvers in 2017. State draws attention to Hollinshed's Chronicles of 1547 where Hollinshed states that fine alabaster was being extracted from Beau Manor 'about four or five miles from Leicester' (so presumably near the later Beaumanor Hall at Woodhouse Eaves).

The first reference to alabaster being extracted at Burton on the Wolds is in William Burton's book on Leicestershire, published in 1622, but written about 1597.

Burton, in the Hundred of East Goscote upon the side of Nottinghamshire. Within this Lordship not long since has been found a quarry of alabaster, and white stone, serving for cutters and picture makers for statues, tombs and proportions but not altogether so hard and clear as that stone which is gotten in the Castle-hay Park near Tutbury, or in the quarries at Falde [Fauld] near adjoining: where in a mount called Nantmorebull, myself have seen a rock of the same stone.

Fauld in Staffordshire was a Burton family estate, and William Burton retired there so it is reasonable to assume he knew what he was talking about.

.jpg)

There isn't much doubt that William Burton was referring to Burton on the Wolds since it is the only Burton in the Hundred of East Goscote. The carving of alabaster for religious sculptures had long-since ceased by the time Burton was alive, although the stone was still being used for sepulchral effigies such as those at Exton and Bottesford. There is no feasible way of knowing which quarries were used for sixteenth and seventeenth century memorials.

About ten years ago Ray State visited the monuments in Prestwold Church. He did not think that any of the Prestwold carvings were from Burton on the Wolds sources. But the tombs at Prestwold all commemorate members of the gentry so presumably a local stone would not carry the same status as that from a better-known and more important quarry.

The quarry at Burton on the Wolds that was new in the late sixteenth century may not have been the first gypsum quarry in the parish. Plausibly it was the successor to earlier ones which did not have alabaster-quality gypsum.

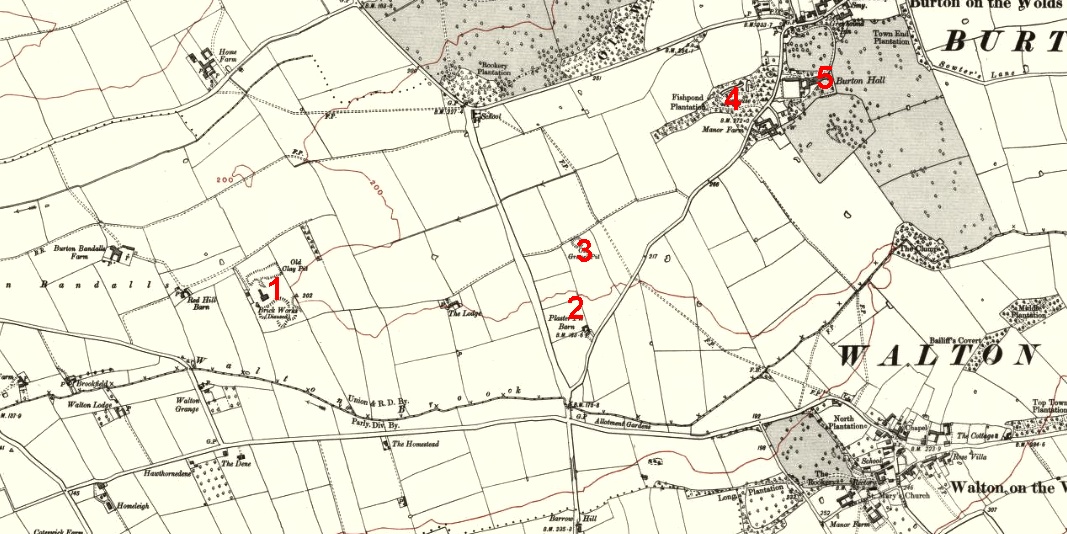

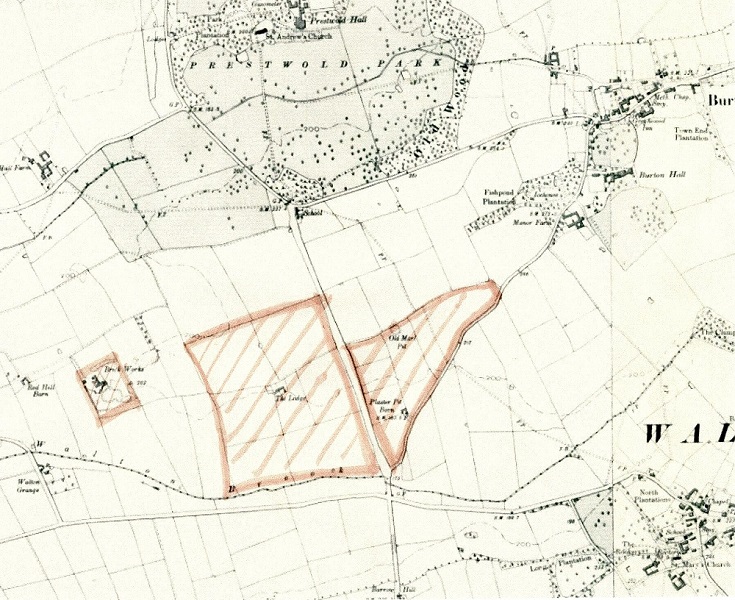

The gypsum or alabaster pits in Burton on the Wolds parish were mainly situated between Burton village and Cotes. A large area of land at the bottom of the present Barrow Road and another large area to the west of the Barrow/Prestwold Road (eleven fields in all) are noted in the estate schedule of 1834 as 'Plaster Pits' and old maps mark 'Plasterpit Barn' close to the junction of the two roads. Fields in this area show mounds reminiscent of spoil heaps, and alongside the footpath you can still see one of the pits (used later as a rubbish tip).

The men who worked at Burton on the Wolds

Burton on the Wolds has no church. Its chapel, St Peter's, fell into disuse in the seventeenth century and there were no separate registers. Cotes had its chapel until around 1700 but although it almost certainly had its own registers they do not appear to have survived. What information we have gleaned about the men working in and around the mines comes from the registers for the mother church at Prestwold. Occupations were only recorded for a few years, and there would be many whose names do not appear in the registers at all, non-conformists and others who neither married, died nor had children baptised at Prestwold. In any case, most of the men working in the mines would have been lost among those described simply as 'labourers', men who earned a living by taking whatever work was available. The following entries refer to men who were probably connected with the alabaster in some way:

In 1577 Tomas Berington of Cotes, freemason was married to Agnes Melbourn.

In 1592 Edward Steward of Burton, labourer, who was digging deep into the earth, was killed and dashed to pieces underneath by a movement of the earth and was buried 22 July.

In 1603 William Pratt of Burton was buried by a sudden movement of earth 22 June.

In 1614 Mattheus Gisbourne, late of Titbury (Tutbury) died 1st February.

In 1623 Gulielmus Werall 'Black Will of the plasterpitts' was buried on 1 May.

In 1699 Henry Stewardson, wid, of Duffield, Derby, stonecutter, was married to Elizabeth Burbage of Prestwold.

In 1700 a son of Benjamin Long, mason, of Burton, was baptised.

In 1704 a son of William White, mason, of Burton was baptised.

The deaths of Edward Steward and William Pratt suggest that gypsum was being extracted by drift mines. And Mattheus Gisbourne's origins in Tutbury suggest that whoever was running the Burton on the Wolds quarry needed to bring skilled labour from the Staffordshire quarries.

Burton on the Wolds gypsum extraction in the nineteenth century

In 1667, 22 year-old John Storer inherited estates in Walton from his father and the 'title and term of years in a Close of Pasture in Burton on the Wolds called Plaster Pitt Close'. John later became a local benefactor and is commemorated in the name of John Storer House in Loughborough.

Plausibly some of Storer's wealth came from Burton's alabaster. When the Burton Hall Estate was put on the market for the first time in 1834 it was advertised as having 'beds of alabaster and limestone'. The catalogue reads 'there are thick beds of excellent alabaster and lime-stone to a great extent, in parts of the estate, which are very valuable, and may be gotten at a moderate expense'.

In 1840, just a few years after the Burton Hall Estate sale, Thomas Rossell Potter (1799–1873) published his book Walks Round Loughborough. In his chapter about Burton Bandals, he talks about the Bandals Farm 'with its steam-engine, brick-yards, and plaster-mines', and goes on to say 'the strata of gypsum, beautifully exposed by a deep section of the earth, are perhaps as curious "fragments of an earlier world" as Leicestershire contains'. The brickyard site he refers to is marked on several old maps and now forms part of the Prestwold Natural Burial Ground. Potter's remarks are the last documented record of gypsum extraction from Burton on the Wolds.

The ponds in 'Fishpond Plantation' are plausibly former gypsum pits. There is also a pit or hollow marked on old maps to the north of the village above the modern Orchards housing development. This may also be from former quarrying. Such pits were not confined within Burton parish boundary. There was a Limepit Close in Walton and both an East and a West Plaster Pit Close in Prestwold.

Quirky endnote: One of the authors (Bob) lives in a house adapted from three of the cottages built soon after 1860 for workers at the 'plaster pits' in Orston, Nottinghamshire.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Paul Sutton and Hellen Jarvis for sharing information.

Sources

Raymond State, The Alabaster Carvers, (Melrose Books 2017).

This blog is based on an earlier article by Joan and Peter Shaw 'Burton Alabaster' available here.

A hand-specimen of gypsum collected from the vicinity of one of the former pits in Burton on the Wolds. Courtesy of Hellen Jarvis.