Sunday 25 May 2025

The English Sparrow – friend or foe?

LAHS Newsletter Editor Cynthia Brown explores attitudes to the house sparrow as an agricultural ‘pest’ in the later 19th century.

Some years ago, when I was researching a course on the Victorians and the animal world, I found a reference to the 1897 – 98 Minute Book of the Lutterworth Sparrow Society in the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland (P91/13). I naively assumed that this was a society for the protection of these birds – but found that its objective was quite the opposite: ‘The Destruction of the House Sparrow’ as an agricultural pest. I subsequently discovered references to Sparrow Clubs or Societies in other parts of Leicestershire, including Long Whatton, Mountsorrel and Waltham, and in the UK more widely. Determined efforts were also made in the later 19th century to destroy sparrows in Australia, New Zealand and the United States.

More of these later – but what was it about this otherwise ‘most inoffensive bird’ that made it the target of mass destruction? The sparrow’s ‘numerous and abominable transgressions against agriculture’, to the extent of endangering food supplies, were described thus in 1856:

In summer this enemy of order pecks the gooseberries and cherries, he devastates cornfields and gardens; in autumn he devours the grapes, fruits and seeds; in winter he takes up a position of observation close to our domiciles, where he selects his quarters; he penetrates into our granaries, where he pillages, he enters our dovecots, and contrary to all the articles of the law, he appropriates to himself the food of our timid doves (Eddowes Shrewsbury Journal, 2 Jan 1856)

One report from Waltham in 1886 referred to damage to the buds on fruit trees as well as grain in the fields at harvesttime, ‘and onions and peas, also suffer from these pests’ (Grantham Journal, 27 March 1886). To this may be added the damage done to the habitats of other birds such as house martins, by taking over their nests in winter: and ‘If the martins build new nests, they turn them out of those also’ (The English Sparrow (Passer Domesticus) in America, 1889).

There are references to Sparrow Clubs in Britain from the 18th century, but their number and the intensity of their activities increased in the later 19th century, along with those of bodies such as Parish Vestries that assumed this responsibility. This was related in part to increased competition from imports of foreign grain at this time, and a need to better protect British crops. However, the Lutterworth Sparrow Society provides some insights into how such clubs operated, and the incentives offered to members to destroy the birds.

It was formed following a public meeting in November 1897, when a committee of 12 was elected to consider the best methods of securing the destruction of the birds (Leicester Chronicle, 6 November 1897). Thirty parishes were represented, and subscriptions varied according to the amount of land occupied by members: 6d for less than two acres; one shilling for 2 - 50 fifty acres; and a shilling for every additional 50 acres ‘or part thereof’. It was resolved that ‘one sparrow at least per acre in each Parish be destroyed annually’, for a payment to subscribers of 3d per dozen dead birds delivered to the club in evidence. More than 2,600 were paid for up to 1 January 1898, and thousands more were recorded in the Society’s half-yearly statement in July that year. Of these, 1,076 were contributed by Broughton Astley. Catthorpe, around four miles south of Lutterworth, accounted for 852, and Ashby Magna and the nearby village of Willoughby Waterless for 222 and 200 respectively (Minute Book of the Lutterworth Sparrow Society).

Sparrow clubs often had a social aspect, both at the counting of the dead birds, and in some cases an annual dinner. The menu at one such event in the West Country in 1856 consisted ‘chiefly of sparrows, served up in every imaginable variety and sauce’ (Eddowes’s Shrewsbury Journal, 2 Jan 1856). In 1898 the Long Whatton Sparrow Club near Loughborough held a supper at a local pub, where ‘the evening was spent in a convivial manner, songs being contributed…’. It was also reported that 1,388 sparrows had been paid for in the two years since the club’s formation (Leicester Chronicle, 29 Jan 1898). In the small village of Throwley in Kent in 1905, ‘justice having been done to the spread… songs and toasts were the order of the evening, most of those present contributing... The National Anthem and Auld Lang Syne brought a pleasant evening to a close’ (Canterbury Journal, 8 Apr 1905).

Sparrows were excluded from the Wild Birds Protection Act of 1880, and destroying their nests and eggs were among the other quite legal means of keeping down their numbers. Other methods included trapping them in nets, shooting them, or poisoning them – by scattering wheat laced with arsenic or strychnine, for example, or using patent anti-vermin preparations such as Greer’s, said to be ‘Patronised by Royalty and the Aristocracy of Europe’ (Farmer’s Gazette and Journal of Practical Horticulture, 9 Jul 1859). The latter were not effective against large numbers and also ran the risk of accidentally poisoning other birds, animals or even humans.

However, the advocates of destruction did not have everything their own way. In Bottesford, in the Vale of Belvoir, such efforts were coordinated by the Parish Vestry, with the costs borne by the ratepayers. This was denounced as ‘unjust’ by those who ‘entirely disapprove’ of the practice – but Christian teachings were invoked on both sides. ‘In the place assigned to man in the world’, wrote one correspondent to the Grantham Journal: ‘power is given him over the beast of the field and the fowls of the air, and he is permitted to use that power for his profit and preservation’. The same edition of the newspaper also published a poem by Florence Nixon of Leicester, described in the 1881 Census as an ‘Authoress Novelist’, asking the farmers of Bottesford to ‘Stay the dreadful sentence’ on Christian grounds:

… We’ve pecked your new-grown wheat, tis true;

But we’ve striven to repay

Your charity by scaring

The insect world away.

To discern ‘twizt good and evil

Was not to sparrows given;

But ‘tis for Christians to forgive,

As they hope to be forgiven…

The Vestry was also accused of ‘brutalising’ children ‘by bribing them to betray and slaughter their little neighbours’: the children of Bottesford ‘may be seen stoning and snaring the unlucky little birds, for the price set on their heads’ (Grantham Journal, 4 Feb 1882; 17 Jan 1885). However, the most powerful arguments against the destruction of sparrows, as the above poem may suggest, were made on what we would now call ecological grounds. No one denied that sparrows played a part in keeping crops free from caterpillars and other insect pests. The only dispute was about whether ‘the good the Sparrow does far counterbalances the evil’: for as the eminent British ornithologist John Henry Gurney warned in 1885: ‘If the balance of nature was upset by exterminating sparrows, we might have to pay an unknown penalty’ (M. Holmes, ‘The sparrow question: social and scientific accord in Britain, 1850–1900’).

The most tragic demonstration of this was the massive increase in insect pests, locusts in particular, following the near-eradication of sparrows in China in the ‘Four Pests’ campaign of 1958, contributing to famines that killed millions of people. However, scientific experiments in the later 19th century did not resolve the question one way or another. The dissection of the stomachs of dead sparrows revealed grain at certain times of the agricultural year, and insects at others, while the ‘casual observations made in the field’, often presented as evidence in the columns of newspapers, were described by one entomologist as ‘either deficient in scientific value or actively misleading’ (Holmes, op cit). The emerging disciplines of economic entomology and economic ornithology - the study of the financial costs and benefits of insects and birds to humans – generally came out in favour of destroying the sparrows, but their conclusions were rejected by others, along with the indiscriminate killing that could result. In 1908, for instance, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), founded in 1889, argued that ‘the wanton destruction of birds’ encouraged by some Sparrow Clubs, among them starlings, blackbirds, larks and bullfinches as well as the sparrows themselves, was resulting in ‘fearful ravages committed by caterpillars in the orchards of Kent’ (Grantham Journal, 3 Oct 1908).

.jpg)

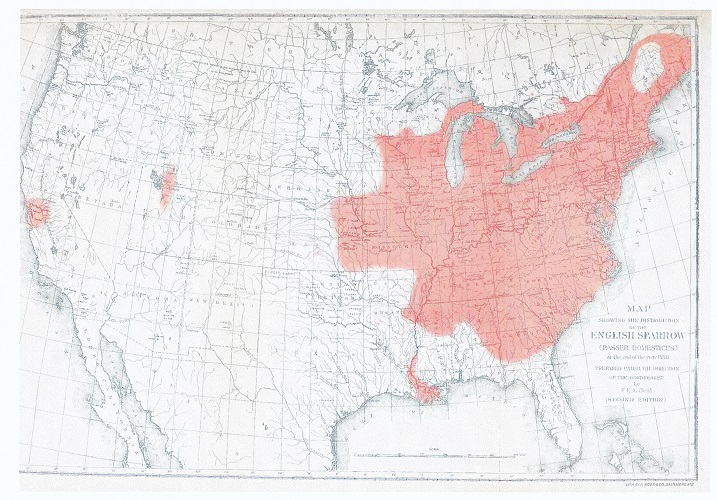

The issue was by no means one for Britain alone. In parts of the United States, Australia and New Zealand sparrows were all the more vilified for being deliberately introduced – as a means of controlling insect pests. Eight pairs were imported to New York around 1850 by Nicholas Pike, Director of the Brooklyn Institute. These did not thrive, but further imports followed over the next few decades to the USA and Canada (The English Sparrow…). Sparrows usually breed prolifically and adapt quickly to new environments. Some were said to migrate by way of the American railway network, attracted by remnants of grain in empty carriages (Holmes, op cit). By the 1880s they had become ‘a curse of such virulence’ - to vines and fruit trees as well as grain - for the US Department of Agriculture to advocate the repeal of all laws affording them protection, along with new legislation to legalise their destruction, and that of their nests, eggs and young (Melton Mowbray Times and Vale of Belvoir Gazette, 16 Sep 1887).

The Department’s investigation, The English Sparrow (Passer Domesticus) in North America, Especially in its Relations to Agriculture, included a section on Australia, where the sparrow was imported from the early 1860s. Here again the intention was to control insect pests, with the secondary benefit of serving as a reminder of ‘home’. ‘I like to see a bird in the streets’, said Edward Wilson, editor of the Melbourne Argus: ‘and I have a kindly feeling for the sparrow for his friendly confidence’ (The Conversation website, accessed 24 Apr 2025). Some were imported from Britain and Germany, but most came from India, the shorter sea journey favouring their chances of survival. A prominent role in these imports was played by the Victoria Acclimatisation Society of Melbourne, founded in 1861, of which Edward Wilson was President. This aimed to introduce and acclimatise ‘all innoxious animals, birds, fishes, insects, and vegetables, whether useful or ornamental’.

‘Never was the truism that it is better to have too little than too much so markedly exemplified…’, remarked the Derby Mercury (5 Jun 1878) of the sparrow problem in Australia:

For ten or fifteen years, perhaps, the Australian gardeners and farmers and the sparrows got on exceedingly well together. The little birds performed all that was expected of them, and the land was well nigh free of grub and caterpillar. Presently, however, there gradually arose a feeling of uneasiness as to the increase and multiplication of the imported blessing.

‘Curses on the head of the sparrow and those who introduced it are both loud and deep’, the Melbourne Argus wrote as early as 1871 (Grantham Journal, 8 Jul 1871). By the 1880s it was said to be ‘playing havoc’ with vineyards in particular. According to evidence from a vineyard owner in South Australia: ‘Sparrows are established in his neighbourhood [sic] in immense numbers, and are very destructive to fruits, especially grapes of the finest kinds.. His loss by them is incalculable’ (The English Sparrow…). Similarly, within a few years of their introduction to New Zealand in 1866, farmers were reported to be poisoning them with a mixture of strychnine and phosphorus to stop them destroying their crops of grain – with the added bonus, it was noted, of keeping down infestations of rats (Otago Witness, 22 Jun 1878).

In Britain, the First World War saw renewed assaults on the sparrow, as it became still more urgent to preserve domestic grain crops (Hansard, 25 Apr 1917) - but Sparrow Clubs, or any need for them, have long since ceased to exist. The increased use of pesticides, a decline in sources of food and nesting sites through changes in farming methods, and pollution in urban areas, saw a fall of over 70% in the House Sparrow population between 1970 and 2008. Concerns now focus on its survival, and it has been on the UK Red List of species of ‘highest conservation concern’ since 2002 (RSPB).

In this context it has perhaps been worth revisiting its status as a ‘curse’ to farmers across the world - along with the questions raised by attempts to destroy it, as they apply more widely. These continue to be as relevant as ever to the ecological balance within the natural world, and its relationship with humans today.

Cynthia Brown 2025. newsletter@lahs.org.uk

Sources

Walter B. Barrows, The English Sparrow (Passer Domesticus) in North America, Especially in its Relations to Agriculture (US Department of Agriculture, 1889), p337 – The English sparrow (Passer domesticus) in North America, specially in its relations to agriculture .. : Barrows, Walter Bradford, 1855-1923 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive (accessed 18 April 2025)

‘City sparrows came to Australia via India’, The Conversation – (accessed 23 Apr 2025)

Eleanor Anne Ormorod - Eleanor Anne Ormerod | Oxford University Museum of Natural History (accessed 4 May 2025)

“If it Lives, We Want It.” Exploring the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria’s Role in Australia’s Ecological History – Biodiversity Heritage Library. Foxes and rabbits were among other imports that proved disastrous. (accessed 23 Apr 2025)

Images of the Rat and Sparrow club, Chelsfield, London - Rat and sparrow club chelsfield hi-res stock photography and images - Alamy (accessed 18 Apr 2025)

Minute Book of the Lutterworth Sparrow Society, 1897 – 98, Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland (P91/13)

Newspapers as cited in the text above.

RSPB - House Sparrow Bird Facts | Passer Domesticus (accessed 2 May 2025)

Matthew Holmes, ‘The sparrow question: social and scientific accord in Britain, 1850–1900’, Journal of the History of Biology (2017) - The Sparrow Question: Social and Scientific Accord in Britain, 1850–1900 - DocsLib (accessed 23 Apr 2025)

‘The sparrow that survived Mao's purge’, The Independent, 3 Sep 2010 - Nature Studies by Michael McCarthy: The sparrow that survived Mao's purge | The Independent | The Independent – accessed 2 May 2025. The other three ‘pests’ were rats, flies and mosquitos.

Background image: Recent photo of sparrow. Image courtesy of John Brown.

Recent photo of sparrow. Image courtesy of John Brown.