Thursday 18 January 2024

The 1645 Siege of Leicester

LAHS member Steve Marquis, recounts the infamous siege of Leicester in 1645 during the height of the English Civil War

“Instead of keeping to their houses, they [the people of Leicester] fired upon our men out of their windows, from the tops of houses, and threw tiles upon their heads” Royalist Officer

After bitter fighting during the last two days of May 1645, the Parliamentary stronghold of Leicester was stormed and captured by the Royalist Army of King Charles 1. What followed would result in the worst atrocity of the English Civil War.¹ Four years later, Charles’s actions in Leicester would form part of the indictment against him at his trial. Four of Leicestershire’s leading political figures would become regicides and sign the King’s death warrant – he was executed 30 January 1649.

Leicestershire, like the rest of the country, was bitterly divided in the conflict between King and Parliament. A split made more intense by the fact that the county’s two most prominent families chose opposing sides. The Hastings family came out for the King and the Greys for Parliament. Apart from the Black Death (1349), the English Civil War would claim more lives than any other event in its history. It is estimated that around 1 in 10 of England’s population perished in the fighting, hunger and disease that attended the most rapine of all conflicts: civil war!

Charles’s absolutist belief in the Divine Right of Kings and his recalcitrant intolerance of any opposition to his rule, would eventually lead to open warfare with Parliament. For over a decade the King ruled as a dictator without Parliament, imposing extremely unpopular policies while imprisoning and torturing those who dared challenge his authority.

Like most towns, Leicester suffered from extortionate and illegal demands from the King for money, in 1635, for example, this amounted to the equivalent to a quarter of the town’s annual expenditure. Similar sums were demanded in 1637, 1638 and 1639. It is no real surprise that Leicester declared for Parliament three years later.

On the 22 August 1642, King Charles raised the Royal Standard in Nottingham, thus declaring war on Parliament and most of his subjects. Perhaps one explanation for the King’s disdain for the townsfolk of Leicester three years later, was that on his journey to Nottingham he was humiliatingly barred from entering the town by the people of Leicester, who refused to open the gates for him. Charles was ignominiously forced to stay at the Abbey just outside the town walls.²

By the spring of 1645 things were going badly for Charles. On the 7 May, the King and his nephew, Prince Rupert, marched his army out of Oxford with the aim of relieving Chester, which was being blockaded by a Parliamentary force. He had not proceeded very far before news reached him that his court was in peril as Parliament’s New Model Army, led by Sir Thomas Fairfax, had laid siege to his new capital at Oxford. Charles hoped that by attacking the important Parliamentary garrison at Leicester, Fairfax would have no choice but to come to its aid and abandon the assault on Oxford. The King summoned virtually all his remaining forces from across the country to assemble at Ashby de la Zouch by 27 May. Gathering all his army together in the hope of forcing one decisive battle and securing final victory.

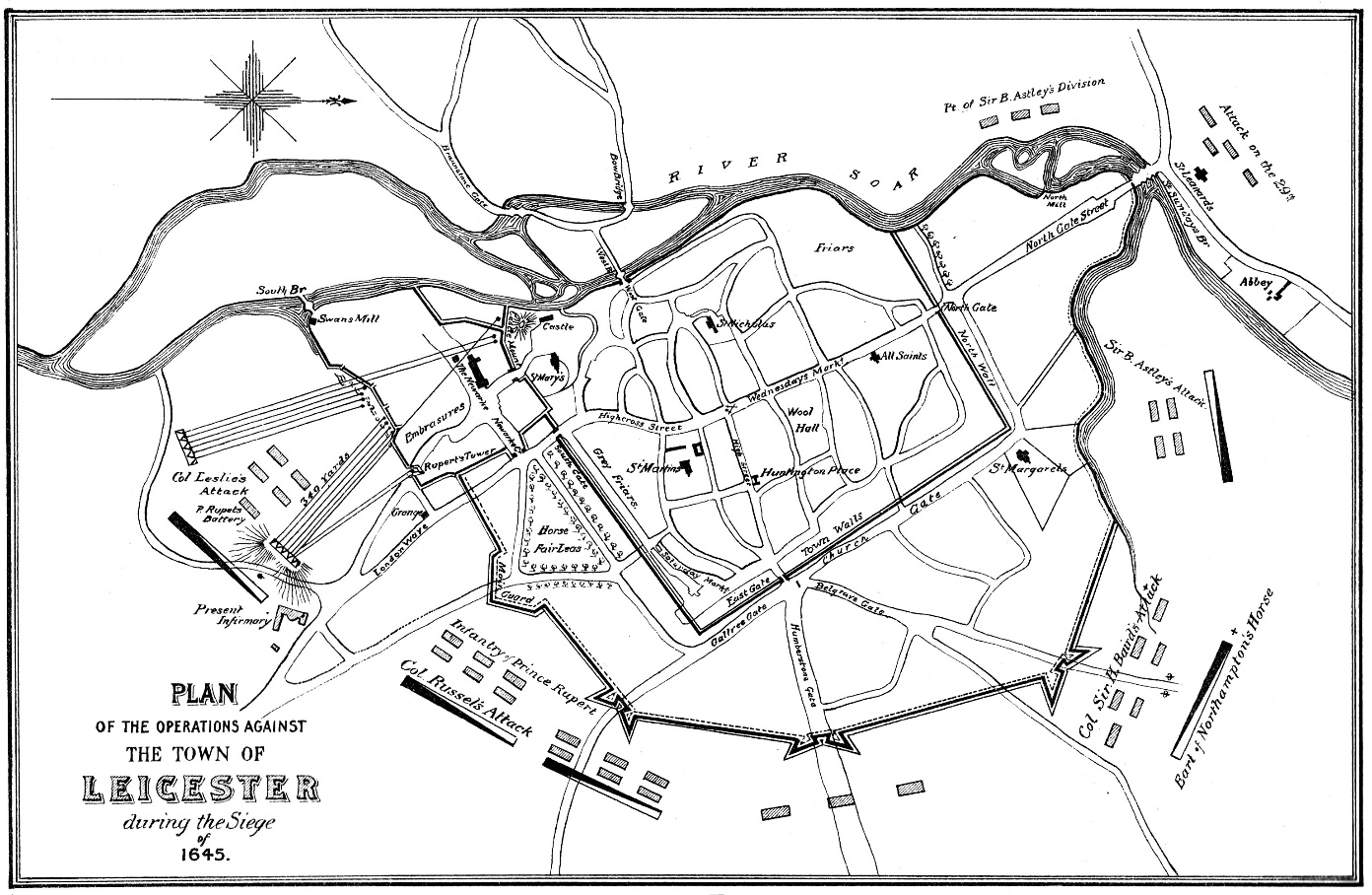

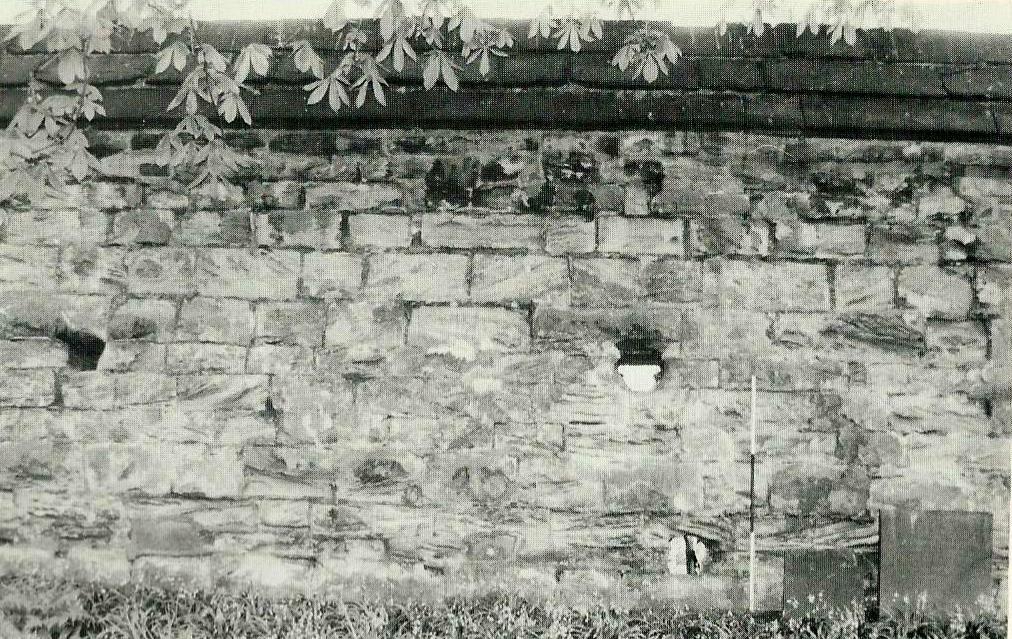

A Royalist army of 10,000 troops arrived at the southern gates of Leicester at 8 am on 30 May. Facing them, under the command of Colonel Theophilus Grey, were approximately 2,000 defenders, including just over 500 trained soldiers, 200 cavalry under Major Innes – who had reached the garrison just before the siege began – and 900 local men aged between 16 and 60. By the middle of the 17th century, Leicester’s Roman and medieval defences were in a poor state of repair and desperate attempts to shore them up were too little and too late – a situation not helped by a shortage of cannons and other military ordnance. Yet this didn’t prevent the defending troops from opening fire on Prince Rupert’s men as soon as they were in range.

After a brief artillery salvo to advertise his own superior firepower, Prince Rupert sent messengers to demand the surrender of the garrison. Leicester’s Lord Mayor, William Billiers, and the Town Committee responded by asking for time to consider their position. Further demands for a surrender were met with continued requests for more time. When the people of Leicester were observed still frantically trying to strengthen defences, Prince Rupert realised the town’s elders were merely stalling and aiming to delay the assault for as long as possible.

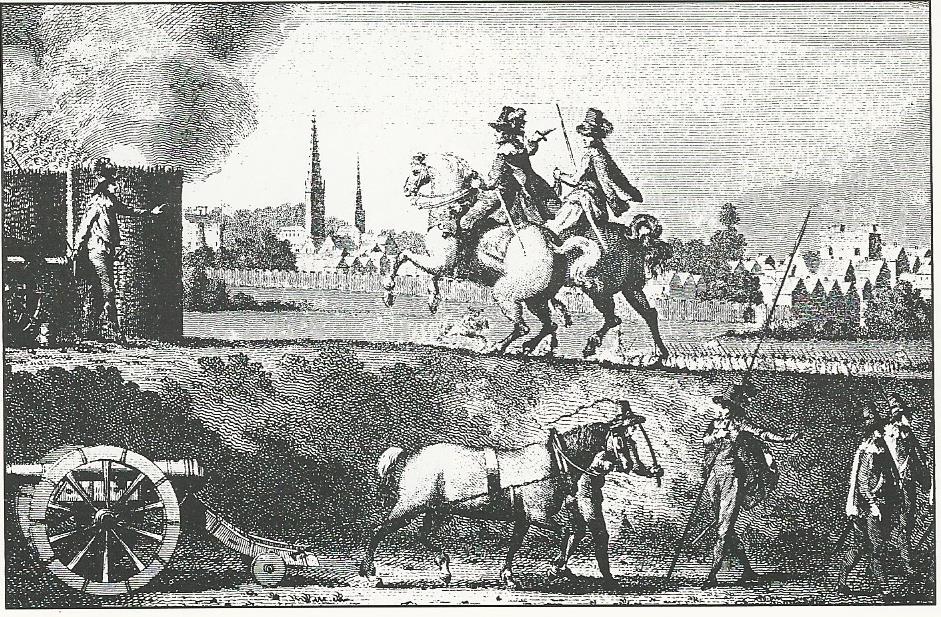

The first assault commenced at 3 pm with a heavy cannon bombardment against the town’s southern wall and Magazine in the Newarke area. Townspeople, including women and children, were seen heroically trying to repair any breaches under constant fire – a sign of the dogged determination that would truly manifest itself a few hours later.

At midnight, Prince Rupert used his overwhelming superiority in manpower to mount an all-out attack on the town. In the south, defenders repelled major assaults on no less than three occasions. Thirty Royalist officers including, Colonel Saint George and Sir Thomas Appleyard, along with many of their men, were killed and even more wounded. So resolute was the resistance here that the King’s soldiers never managed to penetrate into the town from this quarter until the fighting was almost over.

Attacks in the north and east eventually broke through, but again, only after overcoming ferocious resistance. Once inside the town walls, Royalist forces had to fight for every street and house, every inch was contested in vicious hand-to-hand fighting: –

“Instead of keeping to their houses, they [the people of Leicester] fired upon our men out of their windows, from the tops of houses, and threw tiles upon their heads.” One house offered particular fierce resistance “and many shots fired at us from the windows, I had my men to attack it, and resolved to make them an example for the rest. Breaking open the doors, they killed all they found there without distinction.”³

Gradually, greater numbers forced the defenders to retreat for one last stand around the old Market Cross at the top of High Cross Street. Faced with a cavalry charge they finally surrendered. Even so, pockets of resistance still continued for several more hours.

What followed was nothing less than a massacre. Clearly outraged by the ferocity of the defence, drunken Royalist soldiers went on a bloody rampage. Every house was systematically looted, women raped, and hundreds murdered in cold blood. Over 600 were killed out of a total civilian population of around two to three thousand including the mayor and members of the Town Committee who were brutally executed. Charles even seems to have condoned the mistreatment of prisoners: “I do not care if they cut them more, for they are mine enemies.”⁴ Only the names of three victims have come down to us today due to later petitions requesting assistance. One was William Summer, a tailor, whose house was burnt down, his orchard destroyed, and all his possessions stolen. One of five sons was killed, and it was said that William’s wife went insane with grief. Francis Stevens, with six children and Constance Brewin, mother of two, both widows of men killed fighting for Parliament, also sought help.

Sir John Venning of the King’s Army, described their own losses “We tend to our wounded and bury our dead, having lost in all some 300 men… The rebels’ losses were but 100 soldiers, although the townsfolk suffered heavily for their part in the fight.” Venning also refers to the sad plight of the wounded “These poor fellows were most pitiful to see, for some were singed like parched leather.”

Two days later, 140 overloaded carts left for one of the few remaining Royalist strongholds of Newark, carrying every item of any value from the town. Sir John Venning observed that “I fear that our course about this business will not be rapid, for our army is now well encumbered with great quantities of loot. There is not a man in the army that does not have his pockets stuffed with gold and precious things.”

Charles left Leicester and the increasing stench from rotting corpses still unburied on 4 June, then marched south to meet an incensed Parliamentary army heading north to avenge the outrages perpetrated upon the people of Leicester. “More news comes each day of the cruel sack of Leicester. It is said that a thousand men, women and children of the town have been slain…. Our men are enraged at this intelligence and look forward to the day we can avenge this shameful work of the Malignants.” (Nehemiah Swift, officer serving with General Fairfax). Twelve hundred men, under Lord Loughborough (Henry Hastings), were left to guard what remained of the town.

The two armies met on 14 June near Naseby on the Leicestershire- Northampton border – Charles had got his wished-for decisive battle which he hoped would present him with total victory. Oliver Cromwell had joined Sir Thomas Fairfax, bringing together 14,000 better equipped and trained New Model Army soldiers against 9,000 men on the King’s side. Less than three hours after the shooting began, royalist troops fled the battlefield in disarray. Many of those who had raped and murdered in Leicester now met their own violent ends. Naseby would be the turning point. Charles escaped, but from that day he would suffer one catastrophic defeat after another before finally fleeing to his supporters in Scotland. These ‘loyal’ Scottish subjects eventually sold him to Cromwell in January 1647.

Two days after the Battle of Naseby, it was the royalist garrison in Leicester that now found themselves besieged by overwhelming numbers. This time there would be no determined defence. Fairfax ordered a brief artillery barrage to show he meant business and Lord Loughborough surrendered after only few hours of token resistance. Amongst the captured Royalists was Sir John Venning. Nehemiah Swift on entering the town, described the wretched condition of its inhabitants “Many who fought in the siege remained maimed, and will most like do so for many years on account of their wounds.”

The cause for which the people of Leicester had fought and died so courageously was soon victorious, though not to the extent most would have probably wished. The Protectorate under Cromwell could hardly be described as a healthy democracy. And such was the destruction during those last two days of May 1645, that any meaningful recovery would take decades. Leicester had paid a very heavy price in the fight against tyranny.

Notes and References

- Of course, the Royalists weren’t the only side to commit atrocities. Abuse of non-combatants was perpetrated by both sides throughout England. Even greater slaughter of civilians occurred in Scotland, and, of course, Ireland where the gravest war crimes were committed by Cromwell’s forces in the towns of Drogheda and Wexford in 1649.

- It doesn’t look as though Charles enjoyed his stay at Leicester Abbey in 1642. On leaving Leicester after its fall, the King ordered all the Abbey buildings to be burned down, so as to prevent their use in any future siege. The results of that destruction can still be seen in the ruins of Cavendish House.

- Observation by an unnamed Royalist Officer.

- A Humphrey Brown, gave evidence at the King’s trial, claiming that Charles spoke these words when witnessing the abuse of prisoners.

Steve Marquis email address: stephen.marquis@ntlworld.com

This article comes from Volume Two of a series of five books called Wigston – Window on the Past, published by the Greater Wigston Historical Society.

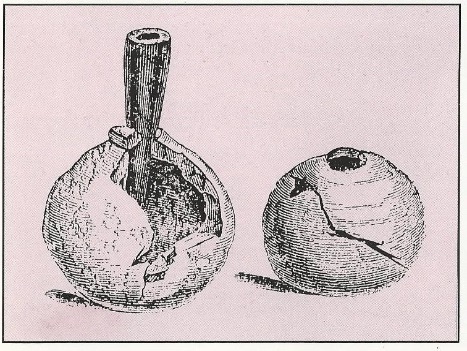

Breach in the Southern Wall, taken from J.F. Hollings, the History of Leicester in the Great Civil War (1840)