Sunday 9 June 2024

‘Something Wicked This Way Comes’ Witchcraft in Leicestershire

LAHS Member Steve Marquis takes a look at the history of witchcraft prosecutions in 17th and 18th Century Leicestershire.

In an age of superstition and life was very precarious, a poor harvest or periods of rapid economic and social change inevitably created fear and resentment, especially amongst those facing severe hardship. Scapegoating people deemed ‘outsiders’ invariably followed, which during the Middle Ages usually meant Jews.

However, from the 15th to 18th centuries this tendency towards scapegoating frequently took the form of allegations of witchcraft against those who were also seen as ‘other’ or ‘nonconforming’ in some way. Between 1542, when the Witchcraft Act introduced capital punishment for those found guilty of ‘diabolism’ (devil worship) and 1736, when this law was repealed, thousands of people in England were accused of being witches and would have suffered hideous torture with up to 1,000 executed, 90% of whom were women. The last known execution for witchcraft in England occurred in Devon in 1685.

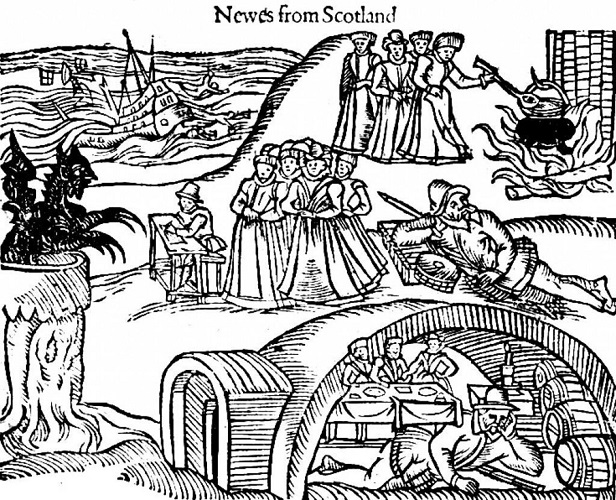

When James Stuart arrived in England as King following the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603, much of population was indifferent or even hostile to the idea of a ‘foreign’ monarch. Thus, he was already paranoid about his safety even before the attempt to blow him and the rest of Parliament to smithereens two years later. In fact, he had feared for his life since a young boy when his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, had abandoned him. Out of this heightened sense of insecurity developed his obsession with witches and demons to such an extent that he even wrote a book on the subject called Daemonologie and is suspected of having personally overseen the torture of accused witches. This book would have a profound influence on the hunt for and how subsequent trials of supposed witches were conducted for the next century, not only in England but across a growing Empire; the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 being the most famous example.

This paranoid preoccupation with witches led James to believe that the terrible storm he encountered on his return from Denmark with his new bride was caused by witchcraft, resulting in the infamous Berwick Witch Trials of 1590, which led to ninety-six people being accused of ‘diabolism’, ninety of them women, of whom seventy went to the stake.

‘Witch-mania’ reached its peak in this country during the first half of the 17th century, triggered by two major events: Guy Fawkes’s attempt to blow up Parliament in 1605 and the Civil War of 1642-51.

Following the Gunpowder Plot a period of almost hysterical anti-Catholic feelings led to large-scale persecution of suspected Catholics including increasing numbers of mainly women being accused of witchcraft as part of the general moral panic. It was in this frenzied atmosphere that the notorious Pendle witches’ trial (in Lancashire, a strong Catholic area) occurred in 1612, eventually resulting in ten people being executed, mainly from two families headed by eighty-year-old matriarchs, both of whom were well-known local ‘Cunning women’ i.e., traditional folk healers and mid-wives. Of the ten who were found guilty eight were women, their fate largely sealed due to the testimony of one of the condemned women’s own nine-year-old daughter.

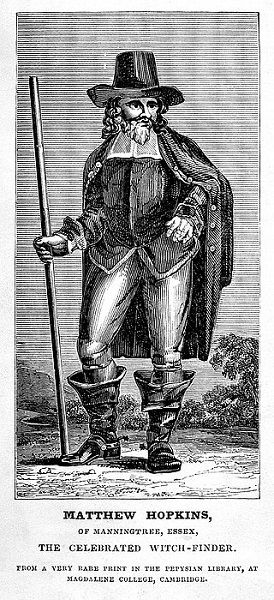

The Civil War had devastated the country after almost a decade of bloodshed, hunger, disease and loss of livelihoods in which an estimated one in ten people died. Into this national mood of foreboding arrived the infamous Witch-finder General, Matthew Hopkins, who, along with others, exploited the fears of a traumatised population.

Hopkins first major intervention was at Chelmsford in 1645, where he ‘uncovered’ 23 female witches, of whom 19 were hanged and four died in prison. Of course, Hopkins charged handsomely for his services, it cost Chelmsford £23 (£4,000 at today’s prices). His clearly extortionate costs and dubious methods of identifying witches, even by the standards of the 17th century, were soon met with growing resistance and Hopkins ceased operating in 1646; he died a year later.

Most of the devil worshiping cases during this period were driven by ambitious politicians or churchmen seeking career advancement, or in the case of Hopkins, financial rewards. In the Pendle incident that person was local JP Roger Nowell who hoped his prominent role would get him promoted out of that remote backwater back to London. It appears that Jennet Device, the nine-year-old child witness whose testimony would send her grandmother, mother and brother to the gallows, had stayed with Nowell’s family in the weeks leading up to the trial. Ironically, twenty years later, Jennet herself would be accused of being a witch but was found not guilty after spending over a year in a filthy prison.

Events in Pendle seem to have strongly resonated in Leicestershire, where two famous witchcraft trials took place shortly afterwards.

Witches in Belvoir Castle

One of the most renowned incidents of supposed witchcraft involved Francis Manners, sixth Earl of Rutland, who claimed to have been the victim of witches Joan Flower and her two daughters, Philippa and Margaret, three servants at Belvoir Castle who had been dismissed sometime in 1613 – just a few months after the trials in Pendle – accused of various forms of “lewd” and ‘irreligious” behaviour.

Soon after, the Earl and his wife became very ill and their two sons, Henry and Francis, died, presumably from the same illness, which was hardly uncommon at this time. It seems the Earl saw it differently and had his recently dismissed servants arrested and taken to Lincoln for ‘examination’. Under torture Joan Flower died and her daughters unsurprisingly confessed to many of the usual stereotypical ‘witches’ practices’, while also implicating three other women as members of their ‘satanic coven’.

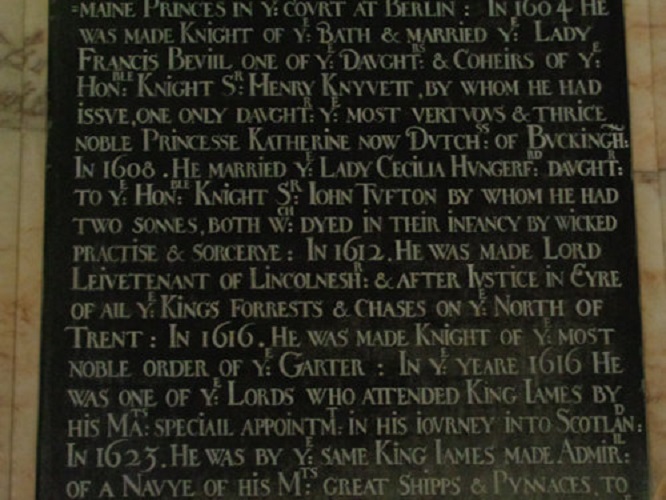

The Flower sisters were burnt at the stake, but the other three women were acquitted and released. Earl Francis’s tomb in St Mary's Church, Bottesford, is apparently the only one in this country that makes reference to witchcraft, it includes the inscription:

“two sonnes, both who died in their infancy by wicked practise and sorcerye.”

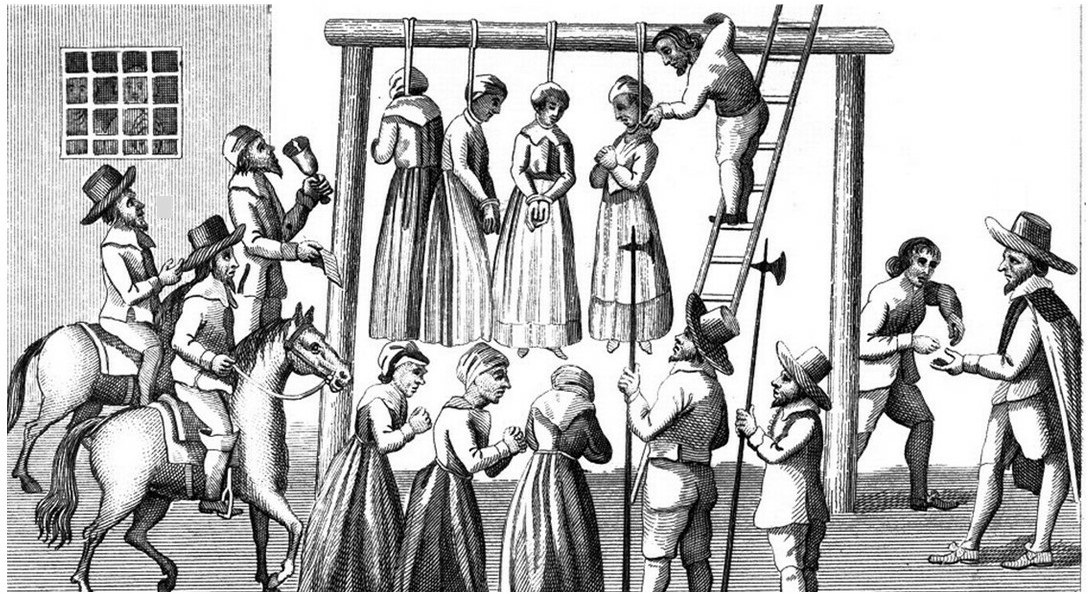

Nine Women Executed on the testimony of a 13-year-old boy

A second and even more bizarre and shocking witches’ persecution occurred at Husbands Bosworth in 1616, again, largely as a result of the testimony from a child. Multiple women were accused of witchcraft by a 13-year-old boy named John Smith, who had been having fits and seizures. This case is referenced in a letter published in 1798 in John Nichols’s The history and antiquities of the county of Leicester, Vol. 2, Part 2. The letter is penned by Alderman Robert Heyrick to his brother Sir William Heyrick in 1616 states: -

"Although we have bene greatly bufyed this 4 or 5 days paft, being fyfe tyme, and a busy fyf speacyally about the araynment of a sort of woomen, Wytches, 9 of them fhal be executed at the gallows this foruone, for bewitching ot a younge gentellman of the adge of 12 or 13 years old, beinge the soon of one Mr. Smythe, of Husbands Bofworth, brother to Mr. Henry Smythe, that made the booke which we call Mr. Smythe's Sarmons."

In short, this records that nine women had been accused of bewitching a 13-year-old boy and were about to be executed. It is also stated that the boy had been having the "most terrible" fits that were indeed so strong that multiple men had been unable to hold him down. He even began hitting himself, sometimes hundreds of times without causing damage. The nine women, who were never named, were blamed for causing these fits through sorcery. Six of the accused women were also said to have had animal-like spirits that tormented the child. and this is also detailed within the same letter where it says: -

"6 of the witches had 6 feverall fperits, one in the lyknes of a hors, another like a dog, another a cat, another a pullemar, another a fifhe, another a code, with whom evary one of them tormented him….”

All nine of the convicted women were hanged on the gallows in Leicester. This wasn’t the end of the story, a few months later six more women were accused of committing similar demonic acts against Smith. Fortunately, for five of the six women, a pardon was granted from the "highe-sherive"; one had unfortunately already died in prison. It seems that the pardon had been directed by the intervention of King James I, who had arrived in Leicester to review the case. Even this witches and demons fixated monarch could see that John Smith was a fraud. It is not known what happened to Smith or whether he was punished for his false accusations.

Witches in Wigston

On the 4 August 1717, Jane Clarke of the village of Wigston Magna along with her son and daughter, Joseph and Mary, were dragged before the court in Leicester by twenty-five of their neighbours who were convinced they were witches. The villagers accused the Clarkes of harassing them with black magic, causing illness and even the death of one villager, Mary Hatchings. In fact, this was the very last indictment for witchcraft in an English secular court.

Witnesses told the court, presided over by Justice Ashby, how the witches’ victims were suddenly stricken with unnatural seizures. The ‘supernatural’ nature of their illness was further reinforced when they began to cough up dirt and stones. At night, the witches gave their victims no peace as they manifested before them, in either demonic or animal form. When the local Church minister failed to break the curse, the villagers were forced to turn to a local ‘white witch’ Thomas Wood (I doubt there were many women designated as ‘white witches’) for help. Wood attempted to remove the curse and identify the witches by boiling the victims’ urine. This curious remedy summoned ghostly apparitions of the Clarkes into the room where they grimaced threateningly at him before vanishing up the chimney.

Once identified, the Clarkes were set upon by a mob of angry villagers. They were violently stripped and searched for witch’s marks and bled to try and break the spells. In his book, Witchcraft, Magic and Culture, 1736-1951, Owen Davies writes that they may have undergone the ‘swimming test’. This meant lowering the accused into a pool or river. If they floated it would be a signifier of guilt. If they sank, the person would be deemed innocent and allowed to live, unless they had already drowned during the test, which was not unheard of. Each of the Clarkes, apparently, floated “like a cork or an empty barrel” according to one witness statement at the trial. Judge Ashby, however, was not convinced and threw the case out of court. By this stage, very few trials of witches resulted in guilty verdicts. However, the outcome would likely have been markedly different a century earlier.

Leicestershire’s last recorded witchcraft related incident occurred in Great Glen, just a few miles from Wigston in 1760, when two old women accused each other of being a witch and even agreed to being subjected to the swimming test, where one sunk and one floated, thus ‘proving’ her guilt. A sort of local frenzy followed, and several old women were attacked for being witches. Witchcraft was no longer a criminal offence by 1760 and the only court case to arise from this incident involved some of the rioters receiving small fines.

In 1735, the Witchcraft Act made it illegal for a person to falsely accuse another of witchcraft. Fraudulently claiming to have magical powers was also made punishable by a fine or a prison sentence under the act. The last known case of a person being imprisoned for ‘sorcery’ in the UK was a woman named Helen Duncan in 1944, who it was said could produce ectoplasm. It was later found that the ectoplasm was cheesecloth.

Steve Marquis email address: stephen.marquis@ntlworld.com

This article was included in the Greater Wigston Historical Newsletter No. 124, November 2022.

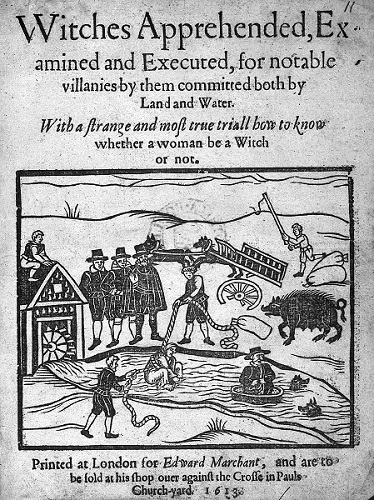

The history of witches and wizards: Collected from Bishop Hall, Bishop Morton, Sir Matthew Hale, etc.(1720) By W.P. (Source Wellcome Collection, Public Domain)