Sunday 7 April 2024

Snakes with glass eyes and other distractions…

LAHS Newsletter and Reviews Editor, Cynthia Brown illustrates the power of sometimes allowing yourself to be driven by simple curiosity and a more random approach when considering local history research.

How do historians decide on the subjects of their research? Much of it is driven by academic imperatives, of course, or contracts for specific pieces of work, or new evidence or interpretations that prompt a revision of previous work, either their own or that of others. Filling in obvious gaps in the historical record, or capitalising on anniversaries such as centenaries are other common motivations; but I would like to argue the value of a more random approach that has served me well in terms of adult teaching and articles I have written for the Leicestershire Historian, and lends itself particularly well to local histories. This is simple curiosity about headlines or entries in documents that have caught my eye in passing and drawn me into exploring their wider context.

Readers of my earlier blog about Severin Wielobycki, a Polish homeopath in Leicester, will know that my research into his life and work was prompted by a one line entry in a street directory; but local newspapers, with their unfailing ability to distract, have been a fertile source of inspiration. Many years ago, well before the age of digital access to newspapers, I was researching a history of Northampton with a fairly tight deadline. On my very first visit to the municipal library I was leafing through a copy of the Northampton Mercury (1 March 1834) when my eye alighted on an item headed ‘Strange Bedfellows’. This proved to be an account of an elderly woman waking one morning to find herself in the embrace of a kangaroo. Probably because I was floundering around with no clear idea yet of what I was looking for, and because it was written in the most dramatic manner - ‘screaming with affright’, ‘visitor from the nether regions’ –I read on…

The kangaroo, it transpired, had escaped from Mr Wombwell’s Menagerie, on display in Northampton at the time, and finding her door open, ‘betook itself to rest there’. Mr Wombwell ‘handsomely remunerated the woman for its lodging’ when he arrived to collect it. Fascinating as this was, it was completely irrelevant to the task in hand, and I did move on quickly to more serious things. Rather than serving as an early warning, however, it was simply a portent of distractions yet to come.

I came across many more stories of escaped animals in the future, either in passing or in more focused research for an adult course that I taught some years ago on the Victorians and their relationships with the world of animals. Often these were lions or tigers, sometimes with fatal consequences, but they also included a ‘huge’ brown bear that joined the morning service at a chapel near Sheffield, making its way to the empty choir stalls, ‘where it lay down and surveyed the surroundings with apparent satisfaction’. Amid much shrieking and crying, and ladies taking refuge in the ‘commodious’ pulpit with the minister, the bear was retrieved by its owner, a travelling showman who had stabled it in a nearby public house (Sheffield Evening Telegraph, 21 April 1890).As it happened, this very random item fitted nicely into a session on ‘performing’ animals, and how far the Victorians had really turned against them by the late 19th century.

Among the headlines that served as a starting point for articles was ‘BANANA PROSECUTIONS’ (Leicester Evening Mail, 30 November 1932). Who could pass that one by? It led me to uncover an unusual episode of passive resistance on the part of street-sellers of bananas (and celery), ‘trying to earn an honest living’ in defiance of bye-laws prohibiting street trading within a large area of central Leicester. At least some were veterans of the First World War, evoking much public sympathy when they were prosecuted and fined - or even imprisoned - for obstruction, to the extent that a leading member of the local Liberal party took himself down to the prison and paid off the fine of one of their number. It was of much wider relevance, however, in its different perspective on contemporary debates about how to deal with long-term unemployment. The same was true of ‘TROUBLE IN THE LAND GRABBERS’ CAMP’ (Leicester Chronicle, 4 December 1909), relating to a protest in which plots of vacant land in different parts of the town were occupied by self-styled ‘Landgrabbers’ demanding that the Borough Council allowed them to be cultivated by unemployed men. It was not unemployment per se that was the target of that protest, but the often humiliating terms on which it was relieved; and it also shed some interesting light on local politics at that time, not least the reluctance of the Labour Party to get involved.

On a lighter note, I was drawn into a fascinating exploration of hot air ballooning in the 19th century -the science behind it, the financing of the various ascents, and its social significance as a ‘spectacle’ - by ‘AN AERO-NAUTICAL BALLAD’ in the Leicester Journal (19 August 1836). This was written in response to a failed balloon ascent by the ‘Lady Aeronaut’ Mrs Margaret Graham from the Wharf Street Cricket Ground in 1836. After hitting a building at the entrance to the ground, the Leicester Chronicle (13 August 1836) reported that the balloon collided with a house on the opposite side of Wharf Street, and Mrs Graham was eventually forced to climb from the car ‘into the chamber-window of the house with which she had come into contact; on the roof of which the lubberly balloon was lying “all its long length”, pulling down the chimneys by its struggles, and rending its brown silken sides’. Or as the ballad put it:

Oh. Mrs. Graham

Unlucky Mrs. Graham!

Beware of all eaves-dropping now, my dearest Mrs. Graham.

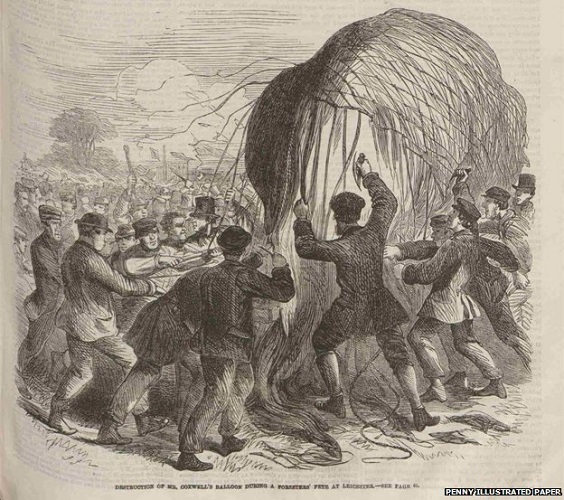

From other sources I discovered that both Mrs Graham and her husband George were somewhat notorious for ‘near-disasters’ with balloons. On one occasion they had to be rescued from the sea near Plymouth, and Mr Graham’s own attempted ascent from the Cricket Ground in September 1836 also failed. It was ‘horizontal, not perpendicular’, in the words of the Chronicle (1 October 1836). Balloon ascents were immensely popular events in the social life of Leicester in the first half of the 19th century, with people climbing on rooftops to observe them; less so as the novelty wore off, but they continued to feature at Flower Shows and similar events, including the Foresters’ Fete on the Racecourse (later Victoria Park) in 1864. Paying customers could react badly to not getting what they were promised, and on this occasion the non-ascent of the balloon of Henry Coxwell, dentist and leading aeronaut, sparked a serious riot in which the balloon was torn to pieces and paraded around Leicester in scenes reminiscent of the destruction of hosiery machinery in 1773.

Mr Coxwell himself had to be escorted from the ground by the police, allegedly to cries of ‘Rip him up’, ‘Knock him on the head’ and ‘Finish him’ (Leicester Chronicle, 16 July 1864); but I need hardly say that not every passing reference calls forth further research. ‘SEAGULL SEEN AT COALVILLE’ (Leicester Daily Post, 6 January 1908) seemed to have potential in terms of climate change, given that this single sighting of the bird, ‘driven inland by the severe weather’ was regarded as newsworthy, but was too vast a subject to tempt me. I should also admit that its main interest was a possible ancestral connection between the person who spotted the seagull hovering over a disused clay pit’ and my paternal family tree. There was none, and I can’t imagine how I would have incorporated it into the family history had there been. Nor is all knowledge picked up in this way necessarily useful - though the fact that parrots can live for up to 100 years might be, if I am ever stuck in a lift for hours on end and every other possible topic of conversation has been exhausted (CRUELTY TO A PARROT, Leicester Pioneer, 5 December 1908).

While I would definitely recommend the random research route, I should add a few words of advice for anyone thinking of following it. The political bias of newspapers is no doubt well known. This tended to be much more overt in the 19th century, as present-day readers of the (Liberal) Leicester Chronicle and the (Conservative) Leicester Journal quickly discern. It is always wise to read both on a particular topic, with the addition from the early 20th century of the socialist Leicester Pioneer. It can also be helpful not to restrict a search in the online British Newspaper Archive (BNA) to newspapers published in or around Leicester. Depending on the topic and the vagaries of syndication, it is not unusual to find something relevant in publications from other parts of Britain, or even national newspapers or journals such as the Pall Mall Gazette and Punch.

I would also say ‘make a note’ if you think a headline might be worth returning to at a more convenient time. How obvious is this? - but it was brought home to me when teaching a two day adult Summer School in which we were exploring some of the references in Wallace’s Local Chronology of Leicester. These were culled from local newspapers, and are in themselves a fertile source of ‘I wonder what that was all about…’. It was then that I made the mistake of mentioning one of the most intriguing headlines I had ever come across, namely ‘SNAKE WITH A GLASS EYE’. Tell us more, said my students; but apart from recalling that this was in the 1930s I couldn’t oblige. By the time I spotted it in passing I had resolved never again to be distracted from the real purpose of my research, and scrolled quickly onwards through the microfilm without even making a note of the date. Right, they said – but can’t you find out before tomorrow?

So that was my evening taken care of. As I didn’t have access to the BNA online at the time, the Internet was my only resort – and the only result it produced was an article in an obscure (to me) Californian newspaper. According to this, the snake was a python at London Zoo named Percy. One of its eyes had to be removed due to an infection, and there were concerns about whether the glass eye would stay in place as snakes have no eyelids. Apart from exclaiming ‘Percy! What sort of name is that for a python?’, my students were quite satisfied with this information, and I was congratulated on my diligence in tracking it down. Once I did have access to the BNA, however, I discovered that what I had seen in passing was a different report about a ‘very rare and valuable Madagascar boa’ (unnamed) at the Zoo, whose eye was damaged by the incomplete shedding of its skin. Once the eye was removed and a glass bead fitted into the socket, the newspaper was pleased to report that the snake became ‘not only well but good-looking too’ (Leicester Daily Mercury, 16 June 1932).

I am not intending to write an article on this theme, nor that of the snake-eating snake acquired by London Zoo in 1875 - Ophiophagus Elaps-Hamadryas Ophiophagus, a variety of King Cobra. Having been acquainted by the Bedfordshire Mercury (3 April 1875) with its ‘hasty natural temper’ and the ‘pretty bands’ on its hood, I feel I know enough. Fortunately, however, the editor of the Leicestershire Historian is never averse to ‘something a little quirky’, so I have taken my inspiration for this year’s contribution from ‘SUNDAY CRICKET IN THE PASTURE. MAGISTERIAL PROCEEDINGS’. All will be revealed in the fullness of time.

Cynthia Brown

Written March 2024

Articles based on the above research by Cynthia Brown

‘This land belongs to all of us – unemployment and the Leicester Landgrabbers, 1909’, Leicestershire Historian, 2015 - ‘This land belongs to all of us’ Unemployment and the Leicester Landgrabbers, 1909 (archaeologydataservice.ac.uk)

‘Trying to get an honest living - an episode of passive resistance’, Leicestershire Historian, 2012 - Trying to Get an Honest Living - an episode of passive resistance (archaeologydataservice.ac.uk)

‘When the Balloon Didn't Go Up’, Leicestershire Historian, 2010 - When the Balloon Didn't Go Up (archaeologydataservice.ac.uk)

* ‘The article ‘Hope against hopelessness: Leicester’s Homesteads for the unemployed’, Leicestershire Historian, 2013 also originated in a newspaper headline - ‘Hope Against Hopelessness’ Leicester’s Homesteads for the Unemployed (archaeologydataservice.ac.uk)

Wombwell's Royal Menagerie, George Wombwell (1777-1850). Public Domain via wikimedia commons