Sunday 4 February 2024

Northfields Council Estate remembered

LAHS Member Dave Fogg Postles looks back on life on the Northfields Council Estate in Leicester.

About a hundred years ago, the newly constituted Leicester City Council embarked upon a programme of construction of council housing estates. Often eclipsed in the media by the earlier Saffron (‘The Saff’ – so eruditely and beautifully delineated by Cynthia Brown) and the Braunstone Estates, Northfields provided new housing for the refugees from the slum clearance in the City. Northfields Council Estate was constructed from the late 1930s on the edge of the town, sandwiched by some private housing, but also on the periphery of the town, a liminal space between the urban and the rural with a porous boundary – street ‘urchins’ invading the countryside. The locality had once been segregated (‘polluted’) space where the Borough Lunatic Asylum had been erected in 1869 . The re-designated Towers Hospital and its grounds backed onto the Council estate.

An estate divided?

The majority of the kids from the estate attended Northfields House school (perhaps regarded as the superior school since its catchment area included the private housing from the Civil War streets and from Gipsy Lane across Catherine Street). A small proportion of the child population was directed to Overton Road (‘Ovo Road’, latterly Merrydale). Ovo Road school had been constructed by the Humberstone School Board in 1881 to provide for the population in the terraced housing in and off that street and off Victoria Road East. It came under the management of the Leicester School Board after the Boundary Extension of 1892. In contrast, Northfields School was not established until 1936 as Northfield Estate was developed. This educational divide determined kids’ social networks. Rarely did kids from the two schools inter-connect.

Ovo Road School had no sports facilities, only a concrete playground. The football and cricket teams therefore played home games on Humberstone Park (Humbo Park) on Uppingham Road, the football team on a seriously sloping pitch. Swimming lessons were conducted at Spence Street Baths.

On the site of Northfields school was Northfields House, for a short time the home of the Quaker John Shipley Ellis who acquired his wealth through his coal business. Ellis, his wife Silena, and family lived there in 1901, transitionally between moving from Knighton Hall to ‘Crosscorners’ in Belgrave. At his death in 1905, his estate was valued at £18, 375. More importantly, perhaps, for the Council Estate, the house became the centre for the local schools medical service, for both Ovo Road and Northfields schools. (Impetigo was rife).

The estate was situated within St Barnabas parish, the parish church situated on East Parks Road. A mission hut (tin tabernacle) was provided, however, on Gipsy Lane, St Gabriel’s. It was the focus for baptisms, if not regular worship. The nearest public library was indeed by the parish church on East Park Road, either a long walk or two bus rides with a change at the Shaftesbury Cinema on Uppingham Road (The Shas).

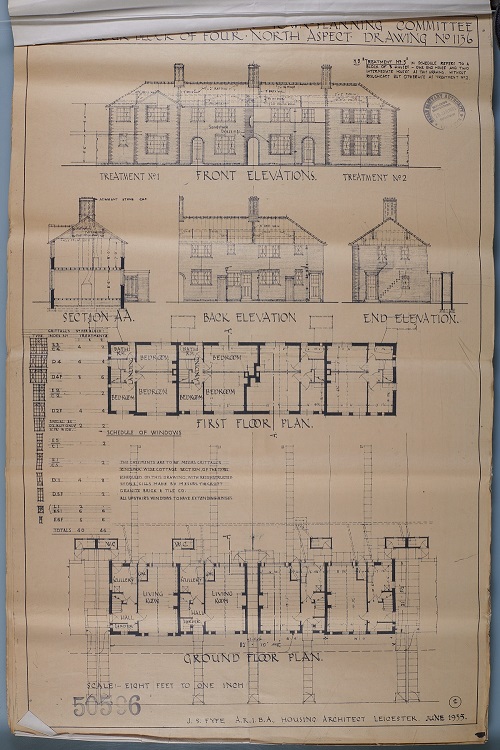

The houses

All the houses were non-parlour type consisting downstairs of an all-purpose through-room and a kitchen. (By contrast, the houses on and off the nearby Tailby Avenue and The Portwey were parlour-type). Many of the houses were constructed in rows of four, in brick with Welsh slate roofs (although a considerable number of bungalows were constructed for the older population). Upstairs comprised one large double bedroom, a smaller double bedroom and a box room, with a cupboard over the stairs. The upstairs bathroom depended on the copper in the kitchen for hot water through a pump which had to be primed. Outside the back door were a coal bunker and the only toilet. In the kitchen, the stoves depended on town gas. The kitchen floor was composed of red quarry tiles. The main downstairs room had a coal fireplace. Two of the bedrooms had small coal fireplaces for hot coals transferred from downstairs. Maintenance of the housing stock was provided through the local works office on The Portwey.

Recreation

After the construction of the estate, a playing field was developed behind the houses on Victoria Road East. It consisted of a flat grassed area which was used for football and cricket by the local kids. Access to other facilities (such as swings and roundabouts) involved a long trek to any of Rushey Mead, Windmill Park (in Humberstone village) or Humberstone Park.

The estate was well provided, however, with local shops: a newsagent (with a private library), a Coop grocery shop (Coop dividend was redeemed at the large Coop store on High Street), a fish and chip shop, a butcher’s shop. And two greengrocers’ shops, all on Victoria Road East and a greengrocery and fish and chip shop on Gipsy Lane. Again, the estate was divided as the inhabitants on one side patronised the Gipsy Lane shops and those on the other the outlets on Victoria Road East. Additionally, the no. 39 bus ran fairly frequently for trips into town to visit the market. An alternative was to walk along Gipsy Lane to Catherine Street for the no. 41.

The beauty of the estate was, of course, that it had housing provision for a wide range of people of the working class. The inhabitants were very mixed. In many ways, nevertheless, it was structurally divided, perhaps inevitably for such a large conglomeration.

Dave Fogg Postles

Acknowledgments

Joanne Spiers kindly located the deposited plan, to whom I owe a great debt. I am grateful too to ROLLR and Joanne for providing the images and to ROLLR for permission to use the images. Copyright belongs to Leicester City Council.

References

National Probate Register 1905 Eabry-Gyles p. 37 (probate valuation of John S. Ellis).

The National Archives RG6/728 fo. 3 (birth of John S. Ellis, 1828)

TNA RG13/3001 fo. 19 (Ellis family at Northfields House); RG11/3126 fo. 73v (Ellis at Knighton Hall).

John Boughton, Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing (London: Verso, 2018)

Cynthia Brown, The Story of the Saff: A History of the Saffron Lane Estate, Leicester (Leicester, 1998)

R. A. McKinley and C. T. Smith ‘Social and administrative history since 1835’, in R. A. McKinley, ed., The History of the County of Leicester

Volume IV The City of Leicester (London: University of London, 1958), pp. 297-8

Janet D. Martin, ‘Schedule of Schools’ , in VCH Leicestershire Vol IV, pp. 335-6

Janet D. Martin, ‘Humberstone’ in VCH Leicestershire Vol IV, pp. 439-42

R. M. Pritchard, Housing and the Spatial Structure of the City:

Residential Mobility and the Housing Market in an English City Since the Industrial Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), pp. 87, 128, Figures 4.8 and 5.1.

Rob Shields, Places on the Margin: Alternative Geographies of Modernity (London: Routledge, 1991)

David Sibley, Geographies of Exclusion: Society and Difference in the West (London: Routledge, 1995)

Victorian Building in Loughborough

A few years ago, a presentation was made by the author to the Loughborough Archaeological and Historical Society about nineteenth-century house building in Loughborough, especially the Paget Estate, as the town received considerable immigration and demographic expansion prior to its incorporation as a borough in 1888.

It can be found here: https://bit.ly/48qkqcc

Ordinance Survey Leicestershire XXXI.4 Surveyed 1938 and published 1945) (CrownCopyright) Reproduced under Creative Commons Licence CC BY 4.0 by permission National Library of Scotland