Sunday 25 February 2024

Luddism and Chartism and the part played by Leicestershire Women

LAHS member Steve Marquis looks at the often overlooked role played by Leicestershire women in these important 19th Century political working class movements.

Below are a few extracts from local newspapers that reveal just how active Leicestershire women, and even older children, were in the strikes, demonstrations and riots during the Luddite and Chartist campaigns of the first half of the 19th century: -

Leicester demonstration by striking stockingers, 26 July 1819

On Monday 26 July 1819, 15,000 or so framework knitters from Leicester and neighbouring villages gathered in St. Margaret’s Pasture calling for the restoration of the 1817 prices and wages settlement. When fellow knitters arrived from Hinckley and Burbage, the crowd marched through the town proclaiming the start of the strike. Prominent among them were women and children carrying placards with pleas such as: -

“Pity the Distressed’ and ‘We perish with Hunger’ reaffirming that the main strategy of the strike was an appeal for wider public sympathy and assistance…” (Leicester Chronicle, 31/7/1819).

“… three or four hundred of the softer sex who had come out of the country to show their zeal for the cause.” (Nottingham Review, 30/7/1819)

Loughborough, August 1819 – The Strike Continued…

“… men, women and boys employed in the trade assembled together in this place and ours [Loughborough knitters] joining them, made a public procession through the principal streets of the town … two thousand marched two by two en militaire with flags dressed in black crape; the women… proceeded the men …” (Nottingham Review, 20/8/1819)

Leicester demonstration by striking stockingers, Saturday 5 June 1824

“On Wednesday, [2 June] their numbers were much increased by the arrival of various divisions [for a demonstration in Infirmary Square] from Blaby, Wigston, Glenfield, Anstey etc. etc., among them upwards of 200 women.”(Leicester Chronicle, 16 5/6/1824)

Riot in Wigston Magna, 8 June 1825

William Thompson of Newton Harcourt (a neighbouring village to Wigston), tried to restart his frames during a bitter strike. Led by George Hort “a great crowd of persons” (LC, 18/6/1825, in the report of his trial) attacked Thompson’s workshop and destroyed his frames when he refused to stop work. Hort received six weeks hard labour as a result alongside two others who received a month. In the following month on 8 June, a riot broke out in Wigston Magna when William Thompson tried to have new replacement frames delivered under the escort of special constables. Thompson described in court what happened as they passed through the village:

“…that on arriving in Wigston they were met by 12 or 13 hundred persons shouting and making use of the most violent language, at the head of whom appeared the female defendant (Elizabeth Vann) who seemed to take a very conspicuous part.”(Leicester Chronicle, 16/7/1825).

Raby’s worsted-spinning factory strike, September 1833

In September 1833, operatives at Raby’s worsted-spinning factory came out on strike in protest at the sacking of some fellow female workers. In the court case that followed five women involved in the strike were sentenced for riotous assembly and assaulting fellow workers Bridget Broad and Mary Higgins. After describing the actions of the five women who: -

“…putting their hands in their faces [Broad and Higgins], using foul language and threatening to ‘leather’ them, unless they would give a promise to become members of the Trade Union.” The magistrate sentenced Eliza Ellimore to three month’s hard labour and Cecilla Marston, Harriet Ford, Anne Bunney and Mary Anderson to one month. (Leicester Journal, 19/10/1833).

Leicester, 18 August 1842 – A Major Chartist Riot

The Northern Star (the main Chartist supporting newspaper) described what happened: “the crowd amounted to twelve thousand; in fact, the Market Place was full. The forces of law and order were drawn up in regimental order, exhibiting their truncheons and dealing out blows upon the people. Having been forced out of the Market Place thousands reassembled at the Recreation Ground on Welford Road, where they heard a number of speeches…. As they marched back towards the town centre along the Welford Road, they were again attacked by Yeomanry which resulted in widespread window breaking, including the New Walk, then a well-to-do area, by those who had been dispersed (Northern Star, 27/8/1842).

“…. however, by 7pm they had returned to the Market Place where hundreds of people, …of whom the vast majority were women, boys and girls but a few men amongst them, belonging to the ‘Shaksperan [sic] Chartists [supporters of Thomas Cooper] gathered outside the Exchange where the Riot Act was read, and the crowd forcibly dispersed.” (Leicester Chronicle, 20/8/1842).

Leicester, Workhouse (Bastille) Riots, May 1848

A large crowd of Leicester’s unemployed and workhouse inmates gathered in Rutland Street on 15 May outside the home of J. F. Winks, Chairman of the Board of Guardians, who had recently announced a worsening of already appalling workhouse conditions. The protest soon turned violent, and the police charged the crowd causing many injuries. The following extract from the Leicester Chronicle on the 20th gives some idea of the ferocity involved in this encounter: -

“…the Mayor, or magistrates, gave the order to the police to clear the street and disperse the assemblage. The policemen – chafed by the insults of the mob, irritated by the stones thrown at them, and anxious to do their duty – obeyed their order with alacrity and courage. Nor were the rioters wanting in determination. They formed a kind of hue and obeyed a ringleader of their own. The conflict, therefore, though brief, was obstinate. There was some hand-to-hand fighting. But the policemen wielded their truncheons with great vigour and effect. They spared no one in their way. The scene became one of great disorder and sharp fighting. The ground was strewn with the bodies of men stunned by the blows they had received. The noise of staves, the groans of those who had been struck, the yells of the multitude and the screams of the women mingled in the crowd, added to the terror of the conflict.”

The following also appeared in this edition of the Leicester Chronicle: -

“… a number of women were very active in exciting to the work of destruction and many of them used their aprons for the purpose of collecting ammunition.”

Although forcibly dispersed, the protesters soon regrouped, and such was the anger and bitterness of Leicester’s poor that three days of serious rioting occurred around the centre of the town.

During the first half of the 19th century (and long after), men wrote the history books – middle and upper-class men – in their own image. The lives of working-class men, let alone working-class women were, therefore, ignored or at best reduced to a generalised backdrop to a national narrative of the great and the good. Until well into the 19th century, most ordinary people were illiterate or semi-literate and consequently couldn’t record their own stories in their own words. Working women were not only disenfranchised from any serious calls for them to gain the vote they were also virtually excluded from the public realm altogether because of both class and gender prejudices. The vast majority of men of all classes – and probably many women – subscribed to the social mores of the time that a woman’s role was as a wife, mother and homebuilder, despite the fact that most working women, as the term implies, were also workers.

Yet it is clear from the above newspaper extracts that Leicestershire women and older children were fully involved in the struggles with their menfolk. Dorothy Thompson in her book on Chartism says that the historical account tends to focus on the most important events and on national leaders – who were all men – thus the involvement of women is usually downplayed, if acknowledged at all. She suggests this picture has changed as attitudes to the role of women have shifted but more importantly, because of more local studies being undertaken that uncover the primary evidence of the full extent of their participation.¹

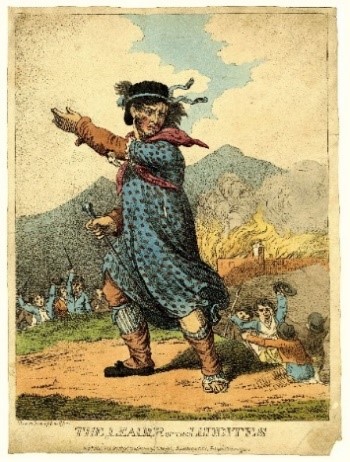

One important source of information comes from transcripts of criminal trials of women as a result of their activities. That’s how we know of the likes of the Molyneux sisters, Mary (19) and Lydia (15) of Bolton or Alice Partington, Anne Dean, Ann Butterworth and Millicent Stoddard of Manchester, who were all brought to court for their participation in Luddite attacks. Ironically, men often dressed in women’s clothes as a form of disguise during their frame-smashing raids, and again later during the so-called ‘Rebecca Riots’ – a sort of revolution in drag.

The attitude of male Chartists and the Movement in general overwhelmingly mirrored the conventions of the day. Women do not feature in the 1842 version of the Charter as a separate entity, only as part of the collective ‘people’ or ‘population’. In the first 1838 draft of the Charter, the “provision for women’s suffrage was cut out because it was said it might make the Charter a laughingstock.”² There were no female Chartist leaders and most of the key male figures were opposed to any equality in the involvement of women; certainly Feargus O’Connor was vehemently against the idea of female suffrage on the grounds that they belonged in the kitchen.

But that said, women were not only fully engaged on the ground, but also organisationally involved to an extent not seen before (although a few women, often Quakers, played significant roles in the anti-slavery movement). There were also several keen advocates of women getting the vote amongst an important minority of leading male Chartists, including William Lovett, John Collins, and R. J. Richardson, all of whom wrote and spoke in support of female suffrage.

A few women Chartists did manage to force themselves onto the national stage, for example, of Susanna Inge, Mary Ann Walker and Anne Knight, generally in spite of rather than with the support of their male colleagues. They did, however, play an important role in the creation of a large number of sizable Chartist women’s sections across the country. In Birmingham they numbered 3,000 at one stage, the Northern Star also recorded other female branches of around 200 or 300 members. The Star also reported on 27 April 1839, that the Hyde Chartist Society contained 300 men and 200 women. The newspaper quoted one of the male members as saying that the women were more militant than the men, or as he put it: "the women were the better men".

Perhaps the most militant group was the Female Political Union of Newcastle: -

"We have been told that the province of women is her home, and that the field of politics should be left to men; this we deny. Is it not true that the interests of our fathers, husbands, and brothers, ought to be ours? If they are oppressed and impoverished, do we not share those evils with them? If so, ought we not to resent the infliction of those wrongs upon them? We have read the records of the past, and our hearts have responded to the historian's praise of those women, who struggled against tyranny and urged their countrymen to be free or die."³

The Chief Constable of Leicester informed the Home Office in April 1848, that he estimated that there were at least 5,035 men and 1,748 women Chartists in the Borough.⁴ Perhaps 10% of the then population.

The first five decades of the 19th century witnessed intense class conflict with numerous strikes, riots, even insurrections, across the entire nation. Such undisguised class warfare drove the country to the brink of revolution in the most violent period since the Civil War. Despite the gender prejudices and barriers women faced in any attempt to play a significant role in any sphere of public life during the 19th century, it has become increasingly clear that they were fully engaged alongside their menfolk in the desperate working-class struggle (even if often unrecorded) against the worsening economic and social conditions generated by the unfolding Industrial Revolution that led to the social turmoil mentioned above.

References

1. Dorothy Thompson, The Chartists: Popular Politics in the Industrial Revolution (1984).

2. Neil Stewart, The Fight for the Charter, 1937.

3. Address of the Female Political Union of Newcastle, published in the Northern Star (2/2/1839).

4. op. cit., Thompson (1984), page 150.

Steve Marquis email address: stephen.marquis@ntlworld.com

This article is based on my book: Luddism, Chartism and the Leicestershire Framework Knitters, 1811-50, ‘A Descent into Hell’.

Illustration of the largest ever Chartist rally at, Kennington Common, 10 April 1848; illustration from The Life and Times of Queen Victoria (1900) by Robert Wilson. Women can clearly be seen on the platform.