Sunday 22 September 2024

Loughborough’s First Workhouse

LAHS Member Dr Pam Fisher explores the founding of an early mid-18th century workhouse.

The workhouses that predate the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 have received relatively little attention from local historians. Loughborough’s first workhouse was built for the poor of the township in 1749–52 on part of Sparrow Hill that was later renamed North Street, then Nottingham Road.

Under the Poor Law Act of 1601, every parish in England and Wales was expressly responsible for the care of its poor. The Settlement Act of 1662 provided everyone with a parish of settlement that was obliged to provide assistance in times of need. The amount and nature of that assistance varied from place to place, with county magistrates able to set a minimum figure. It was funded by a rate (tax) levied on the owners of land and property in the parish, set and collected by elected overseers of the poor (four were chosen annually in Loughborough) and churchwardens. Parishes had authority from 1601 to buy flax and hemp for the poor to turn into cloth, and from 1723 a parish could purchase or rent a house for lodging, maintaining and employing the poor.

Alongside poor relief paid by the overseers, from at least the 1730s until 1807 Loughborough’s Burton charity provided small amounts of cash to poorer residents for short-term needs, and supported those who were ‘just about managing’, where a small sum could ensure continued self-sufficiency, for example by covering rent, or purchasing a spinning wheel for a daughter, or a shovel for a labourer. This ceased in 1807, when the charity began to comply with a decree of 1652 issued by a Commission for Charitable Uses. This required the charity’s income to be spent on repairing the town’s bridges and maintaining the schools, with any annual surplus paid to the overseers. This arrangement ceased in 1840, on the instruction of the Attorney General, enabling the creation of the girls’ High School in 1849 and the opening of the new boys’ Grammar School in 1852.

At a meeting in January 1748/9, 34 of Loughborough’s principal inhabitants and ratepayers concerned about the cost of poor relief were unanimous in agreeing that the town should have a workhouse. A further meeting four days later agreed by a vote of 24 to 11 that this would best be provided by converting a property on Sparrow Hill rented by Robert Roberts from the Burton charity.

The registers of All Saint’s church in Loughborough identify a Robert Roberts who married Bridget Thornton in Loughborough in 1711. She died in 1727. The following year a Robert Roberts, probably the same man, married Mary Alcock in Loughborough. She died in 1729. A Robert Roberts was elected Bridgemaster in 1739, the senior officer of the Burton charity. Bridgemasters were chosen annually ‘by the most reputed, honest, and substantial men’ of the town and a study by Peter Clark of the bridgemasters and feoffees (trustees) of the Burton charity between 1780 and 1840 shows that they were drawn from an ‘elite’ of gentlemen, farmers and substantial businessmen, including hosiers, maltsters, drapers and innkeepers. Robert Roberts the bridgemaster may have been the maltster of this name who died in Loughborough in 1753, two months before his widow Elizabeth. Their marriage does not appear in local records, and we cannot tell whether he was the Robert Roberts appearing in the parish registers in the 1710s and 1720s, or if he had been the occupier of the house on Sparrow Hill.

The Burton charity owned 19 houses in Loughborough in 1749, with annual rents ranging from £1 3s. to £16 (median £4), with Roberts paying £3. The feoffees agreed to serve him with notice to vacate the house in March 1749, subject to a meeting of the ratepayers agreeing to proceed and to provide security for the annual rent. The feoffees agreed to allow Roberts ‘some small conveniency for the keeping of his service and a small garden spot on the said premises’. Perhaps the split in the second vote reflects some qualms among the ratepayers about asking a good tenant and ‘servant’ of the charity to leave his home. The parish agreed to pay ‘the usual annual rent’ together with all rates and taxes, and to keep the workhouse property in good repair. The churchwardens giving their agreement were Samuel Capp and Thomas Farrow (surnames that regularly appear in the list of bridgemasters), and the overseers were John Adams, Martin Newberry, John Cooke and Ben Webster.

The charity’s feoffees agreed that the existing buildings on the site could be demolished and a new building constructed. In March 1749 they appointed John Alleyne, the usher (second master) at the grammar school (and their employee) to contract with the workmen. The building costs of £172 were paid by the Burton charity. The workmen and suppliers included Thomas Peat, Mr Preston (for bricks and nails), Thomas Harrison (a pump and fencing), Thomas Bonsar, Mr Mansfield, Edward Savage, Mr Beaumont (lime), Mr Webster (door knocker and lock), George Farrow (straw), Thomas Bradshaw (carriage of straw and clay) and Widow Gutteridge. Some of these had been involved in building a new school the previous year, also funded by the Burton charity. The workhouse could house 70 paupers. It was described in 1855 as having three storeys and measuring 44 feet by 33 feet.

The parish overseers and churchwardens spent £60 on furniture and covered the running costs, initially amounting to c.£20 monthly. Edward Watts was appointed as ‘master or governor’ of the workhouse. A set of rules included clauses regarding oversight of the management of the house and the finances. Only paupers ‘likely to be a continuous parish charge’ were to be admitted, and in the case of children they were to be taught how to spin wool and flax and knit stockings, so they would be able to get a job outside the workhouse in due course. Adults were able to take work outside the house ‘charring’ or as day labourers. Any cloth or clothing made was to be used within the workhouse – a recognition that the sale of these goods could exert downward pressure on prices and harm local businesses and employment. Paupers in the workhouse were to attend church or chapel twice every Sunday. They were to go to bed in the winter months at 8 pm ‘to save fire and candle’.

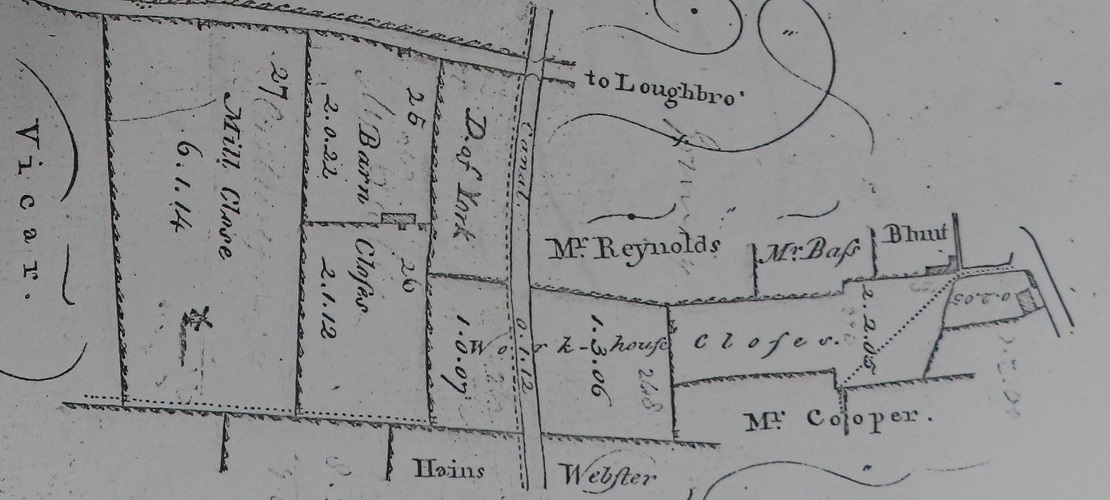

In 1753 the parish officers requested the use of a neighbouring piece of land and in 1755 the Burton feoffees agreed to enclose land adjoining the workhouse garden for the use of the workhouse. A plan of the Burton estate in 1793 shows two buildings on a site of 2 roods 5 perches and three ‘workhouse closes’ totalling 5 acres 1 rood and 18 perches stretching from the workhouse site to and also beyond the Leicester canal.

There were 60 residents in the workhouse in 1803, when the total annual cost of maintaining Loughborough’s poor was £1,713. Loughborough’s population was expanding, but the town’s main industry, hosiery, was declining as fashions changed and the number of people needing ‘permanent’ relief was growing. The overseers had ceased to buy any materials to spin or knit, suggesting that the building now only housed those unable to work from age or disability. The concept of setting the able-bodied poor to work for their living was failing nationally, due to the cost of supervision and the impact on the local economy of selling the production. By 1815 there were 29 adult residents in the workhouse, but ‘permanent’ relief was also provided to 180 adults outside the workhouse, and occasional relief to another 205 people, at a total cost of £2,012.

The workhouse closed in 1839. The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 introduced a centralised system under nationally appointed Poor Law Commissioners, and Loughborough became the hub of a Poor Law Union of 24 parishes and townships in north Leicestershire and south Nottinghamshire. A large Union workhouse for 350 paupers was built near Regent Street, which opened in January 1839.

The former workhouse property continued in the ownership of the Burton charity. In 1839 troops were called out over concerns about a Chartist meeting in the town, and property owners expressed a wish to see a permanent army presence in the town. The army was willing to agree if suitable barracks with stabling for 50 horses was made available. The Burton charity agreed the recently vacated workhouse building could be used for this purpose, and between £500 and £700 was raised by voluntary subscription for the conversion of the premises.

A detachment of the 9th Dragoons became resident in September 1839. Other detachments of cavalry followed in close succession until 1854, when the Royal Scots Greys left Loughborough for the Crimea, leaving the barracks in the charge of ‘two pensioners’ until 1855. They were then discharged, and the army removed the furniture and remaining stores to Nottingham. The feoffees advertised the site as available to let, with the former workhouse building, a yard of 44 yards by 24 yards, other buildings of two storeys, ‘lofty Stables for 50 horses (with a granary over part), Straw Chamber, Smiths’ Shops, &c.’ There appear to have been no immediate takers, but the site was occasionally used by troops passing through the town and by Loughborough’s Rifle Corps. The property was advertised for sale in 1866.

The Star Foundry Company Ltd, an iron and brass foundry managed by Edwin Cooke, rented the premises from 1867. The freehold was conveyed to Messrs Messenger, Taylor and Cooke for £700 in December 1869 for use as a foundry, and continued to be occupied by the Star Foundry until the 1960s (Map 3 and Figure 2). Following the demolition of these premises in the 1960s, the site became a Royal Mail Delivery Office and yard in 1966 (Figure 3).

Pamela J. Fisher

Email: pjf7@le.ac.uk

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Loughborough Library for permission to reproduce Map 1 and Figures 1 and 2 from their collections, and is very grateful to The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland (ROLLR) and to Woolley, Beardsleys & Bosworth LLP of Loughborough for their permission to reproduce Map 2 (ROLLR reference DE664/65). Map 3 is reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ under CC-BY (NLS) licence. The image at Figure 3 is by the author, who would also like to thank the volunteers at Loughborough Library Local Studies for their help finding images and discussing the location of this building and Carol Cambers for providing her thoughts and comments on the images.

Sources

The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland

DE641/1 (Burton feoffees’ minute book, 1849–60)

DE641/7 (Burton feoffees’ accounts and list of Bridgemasters)

DE664/31 (Burton feoffees’ memorandum book, 1736–72)

DE664/34–6 (Bridgemasters’ accounts, 1733–1827)

DE664/41a–b (Burton charity order books for the relief of the poor, 1754–1819)

DE664/65 (Survey of the Burton Estate, 1793)

DE2857/177/1 part II (Notes by Dimock Fletcher, including extracts from Burton feoffees’ order book, 1819–49, and Burton feoffees’ minute book 1865–74 that are no longer extant)

DE667/177, 667/178 a-b (Overseers’ accounts, 1745–1800)

DE667/3 (Parish registers, All Saints’ church, Loughborough, 1705–48)

Admons & wills, 1753 A–S

Parliamentary Papers

1776–7, vol. ix, Report on Returns made by Overseers of the Poor

1803–4, vol. xiii, Returns Relative to Maintenance of the Poor

1818, vol. xix, Returns Relative to Maintenance of the Poor

1839, vol. xv, Report of Charity Commissioners

British Newspaper Archive

Various Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire newspapers

Secondary Sources

P. Clark, ‘Elite networking and the formation of an industrial small town: Loughborough, 1700–1840’, in J. Stobart and N. Raven, Towns, Regions and Industries: Urban and Industrial Change in the Midlands, c.1700–1840 (Manchester, 2005), 161–175.

A. White, A. History of Loughborough Endowed Schools (Loughborough, 1969).

The Author

Dr Pamela Fisher is presently researching a history of Loughborough since 1750 for Leicestershire Victoria County History Trust, which is to be published in two paperback volumes. The first of these will be a social and cultural history of the town, and will include the history of the town’s two workhouses. She has recently published online a history of Loughborough’s second workhouse, which is available here. She acknowledges with thanks the support given by Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society to Leicestershire Victoria County History Trust to help with this research.

The former Loughborough workhouse pictured in the 1960s, shortly before demolition. Reproduced with the permission of Loughborough Library.