Monday 1 April 2024

Leicestershire and Rutland’s Holy Wells

LAHS Member Bob Trubshaw takes a fresh look at some of the area's Holy Wells, exploring both their roots and the folklore surrounding them.

What is a 'holy well'?

As with all areas of Britain there are certain wells in Leicestershire and Rutland known as 'holy wells' and several dedicated to saints. Almost invariably such holy wells have reputations for clean water and for never running dry. Presumably most such wells have been flowing continuously since the last Ice Age. Before piped water such a dependable source of unpolluted water would have been treated with reverence.

Holy wells are not, as many people might imagine, brick-lined shafts. Instead they are springs where water naturally flows out at the surface. The Old English word wella means 'spring' and the first few yards of water running away from the spring.

The adjective heilag is found in every Germanic language, derived from the noun heil ‘omen, good fortune’ which also yielded an adjective heil ‘whole, healthy’. In its original sense, heilag must have had the senses of ‘awesome, strong in power, knowing what is to come, fortunate’.

Tristan Hulse's research into Welsh wells led him to conclude that a 'holy well cult' was part of a whole 'package' of Mediterranean Christianity adopted in the British Isles around the eighth century, of which the most noticeable feature was the veneration of numerous saints.

Barrie Cox's survey of the place-names of Leicestershire and Rutland lists about twenty-one examples of holy wells: Arnesby, Ashby de la Zouch (probably two or three different wells), Aylestone, Beeby, Burrough on the Hill, Burton Lazars (also known as St Ann's Well), Caldecott, Claybrook Parva, Cranoe, Croxton Kerrial, Hinckley (where there is still a Holy Well Inn), Kirby Bellars, Loughorough (Holywell Haw), Measham, Ratby, Rothley, Seagrave, Shawell, Slawston and Thurmaston.

In addition Church Langton had a St Anne’s Well, Hallaton a St Morell's Well, Hungarton a Lady Well (presumably before the Reformation 'Our Lady's Well', i.e dedicated to the Virgin Mary), Leicester had both St Augustine’s Well and St Sepulchre’s Well, Lubenham a St Mary's Well, Lutterworth a St John's Well, Market Harborough had a Lady Well, as did Nevill Holt, and Syston was once home to a St John's Well.

Cox has identified two 'Cross Wells' and seven examples of 'Seven Wells'. Bear in mind seven once had an 'extramundane' sense rather than denoting literally seven sources of water.

Place-names can be deceptive. Holwell Mouth, the source of the River Smite, is not a contraction of 'holy well' but of 'hollow well', in the sense of 'well in a hollow'. There are other probable examples of 'hollow wells' at Arnesby and Wigston Magna.

In this blog I will share examples of Leicestershire and Rutland's surviving holy wells. A much longer and more comprehensive survey is available as a free PDF.

Ashwell

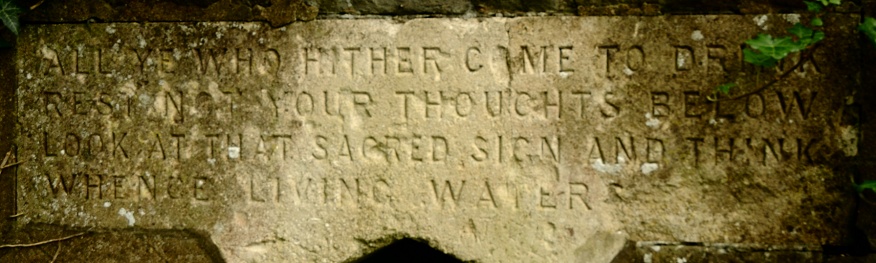

In his 1985 book Roy Palmer referred to ‘the so-called Wishing Well… It has also been referred to in the past as the Holy Well’. However this is the only documented evidence for it being a holy well. But for once this 'really is' a holy well. In a way... Because it has a scriptural inscription which reads:

All ye who hither come to drink

Rest not your thoughts below

Look at that sacred sign and think

Whence living water[s flow]

The inscribed stone has clearly been inserted later into the 'dog kennel' style well house (probably of the late eighteenth century). The cross on the roof was replaced in 2000 as the previous cross had broken off before 1986.

This inscription is closely matched by the words on a conduit-head at nearby Greetham. This reads:

All ye who hither come to drink

Rest not your thoughts below

Remember Jacob's Well and think

Whence living waters flow.

Jacobs Well is a modern Protestant spring-name, first recorded in 1674, coined in allusion to John 4: 1–14

Greetham's conduit house was designed in the High Gothic style fashionable around 1880, just when the Scripture Movement was underway. My guess – and it can be no more – is that the residents of Ashwell were miffed that Greetham's conduit looked better than their 'holy well' so commissioned the inscription, presumably also in the 1880s.

Ryhall

Just as place-names such as Holwell be deceptive, so too can folklore and 'folk etymologies'. According to tradition, there was once a St Tibba's well and a St Eabba's Well in Ryhall. The source of this William Stukeley's Diaries and Letters (vol.3 167–70) as paraphrased by Charles Billson (1895: 21–2). Roy Palmer's 1985 book on Leicestershire folklore summarised things thus:~

St Tibba, niece of King Penda of Mercia, and her cousin, St Eabba, are said to have lived at Ryhall in the seventh century. At first they were 'wild hunting girls', but later became holy hermits. The present church at Ryhall is supposed to have been built over the cell of St Tibba, who, because of her early love of the chase, is the patroness of falconers and wildfowlers. She was buried at Ryhall, but in 936 her body was transferred to Peterborough. A tradition which has lived for more than 1,000 years in the village is that she used to walk up a hill to wash at the spring which is named after her. The spring in turn gave its name to the hill, but over the years this became garbled, first to Tibb's-well-hill, then to Stibbal's-well-hill. On the brow of this hill, near the spring, is Halegreen (the first syllable of which may signify 'healthy'), where gatherings in honour of St Tibba were once held on 14 December – the day of her translation, and perhaps more congenial to wildfowlers than that of her official feast, 6 March.

St Tibba's cousin, St Eabba, also had her spring, near the River Gwash. St Eabba's Well is now called Shepherd Jacob's Well. The ford on the river nearby, originally St-Eabba's-well-ford, is now Stableford, or rather Stableford Bridge, since the ford is no longer used.

(Palmer 2002: 35–6)

As 'folk etymologies' go I've seen plenty worse. Let's start unpicking Palmer's version. Halegreen is not attested before 1979 so Old Scandinavian heill seems unlikely to be the origin. The Victoria County History of 1935 has 'Stablesford Bridge' (note the medial 's'). Barrie Cox dismisses the 'popular etymology' of St Eabba's well (Cox 1994:163). Instead he suggests that this was once a stapol ford – a ford over the River Gwash marked by a large post (Old English stapol) that may have been carved as a pre-conversion icon.

Having negated the existence of St Eabba, Cox attests to the reality of St Tibba, although noting that the earliest mention of 'Tibba's Well' is 1935 in the VCH. Tibael Hill and Tipple Hill Furlong are the seventeenth and eighteenth century forms (Cox 1994: 164). So, although St Tibba had a hill named after her, the available evidence suggests she only had a well named after her sometime not too long before 1935.

Whitwell

'Well' forms part of three settlement names in Rutland (Ashwell, Tinwell and Whitwell) but Cox gives no instances of halig wella in minor place-names anywhere in Rutland (Cox 1994). But this doesn't mean there wasn't a 'holy well' at Whitwell.

The village takes its name from the 'white well'. At the time of the formation of this toponym the word 'white' had connotations of 'clean and pure', as it still does. So the 'white well' would have been regarded as somewhat sacred.

The parish church of St Michael and All Angels is situated on a large mound (made all the more prominent by cutting away the churchyard on the north side and creating a retaining wall to reduce the severity of the gradient of the Stamford to Oakham road (A606)). No stonework surviving in the church suggests a pre-Conquest origin. But the size and proportions of the nave strongly suggest an early single-cell building with a chancel added later.

A spring rises up underneath the stone floor of the chancel; the water is piped to a 'conduit head' at the side of the road to the east of the churchyard. Numerous people have reported that after heavy rain the water can be heard flowing under the chancel floor.

Seemingly the single-cell church was built to the immediate east of the White Well, de facto making it a holy well. The water may have been used for baptism (around the seventh and eighth centuries baptism was usually by affusion not immersion). When the fashion for adding chancels arose then the building needed to be extended over the well. The same scenario arose at Whitwick (see below) and at other churches in Britain (such as Romsley, Worcestershire, where St Kenelm's Well has been recreated to the east of the chancel; also at Wells, Somerset, where spring-fed pools are located to the east of the cathedral that takes its name from these water sources).

The well under Whitwell church is unusual in being on the summit of a small hill. This may have been one of the reasons it was venerated. Technically it is an 'artesian well' fed with water from higher ground to the north.

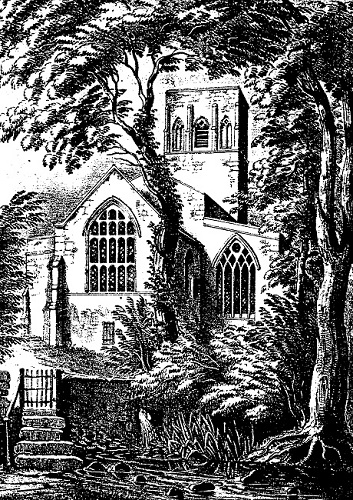

Whitwick

The place-name indicates a white dairy farm or trading place. The parish church of St John the Baptist is located in a natural amphitheatre. This is unusual. As is the spring rising up underneath the chancel and piped to the bank of the Grace Dieu Brook. The water flowing out into the side of the brook maintains an almost constant rate and temperature.

The location of the well suggests an early singe-cell church later extended with a chancel; see Whitwell above for the same scenario. Unlike Whitwell, the church at Whitwick seems to have been extensively rebuilt around the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The oldest visible part of the church's structure is the base of the tower, which is twelfth century. However the eroded fragment of an Anglo-Saxon cross-shaft now incorporated into the south wall of the chancel indicates that this has been a place of Christian worship since at least the tenth century.

Wymeswold

In the late twelfth century there were several references to 'Wolstonwell' and 'Wulstanwellesice' (Cox 2004: 282). While this could take its name from a secular person called Wulfstan more probably it indicates a well dedicated to St Wulfstan of Worcester (circa 1008 – 20 January 1095), although such dedications are otherwise unknown in the county.

This would be consistent with a pre-Reformation dedication for the well which rises to the west of the churchyard mound. At some time, perhaps the nineteenth century, the water source was covered with a pump and the run-off culverted. It gives its name to the street running over the culvert, The Stockwell. Old English stocc wella denoted a simple wooden bridge over the run-off from a spring. This is consistent with the formation of 'Wulfstan well syke'. The culvert discharges into the River Mantle at the southern end of The Stockwell. The water flows almost continually.

To me it seems most probable that a well near a churchyard wall would once have been dedicated to a saint. While I have no way of confirming that before the Reformation the Stockwell was also known as Wulstanwell there is no other natural spring in the village.

If you want to discover more about Leicestershire and Rutland's wells – and perhaps plan some trips to visit them – then please download my free PDF.

Bob Trubshaw

Email: bobtrubs@indigogroup.co.uk

A video version of this blog is also available here.

Acknowledgements

At least eight people have taken a serious interest in Leicestershire's holy wells, starting with John Nichols at the end of the eighteenth century. A hundred years later Charles Billson's pioneering study of Leicestershire folklore includes a few of the named wells. The first county-wide survey was by Lindsall Richardson, published in 1931. In 1985 Roy Palmer published his study of folklore in Leicestershire and Rutland, including several references to wells. The first person to look specifically at the holy wells of Leicestershire was Clive Potter. I published a preliminary gazetteer of holy wells in Leicestershire and Rutland in 1990. In 1993 James Rattue published ‘An inventory of ancient, holy and healing wells in Leicestershire’ in the TLAHS. in the TLAHS Jeremy Harte's English Holy Wells: A sourcebook appeared at the end of 2008. Many more examples of 'holy well' have come to light in the volumes of Barrie Cox's place-name survey published since 2008.

My debt to all previous researchers is considerable, especially to Barrie Cox. Thanks to Gillian Rawlins for requesting this overview.

Principal sources

Billson, C.J., 1895, County Folklore: Leicestershire and Rutland, Folk-Lore Society.

Cox, Barrie, 1994, The Place-Names of Rutland, English Place-Name Society.

Cox, Barrie, 1998, The Place-Names of Leicestershire Part 1: Borough of Leicester, English Place-Name Society.

Cox, Barrie, 2004, The Place-Names of Leicestershire Part 3: East Goscote Hundred, English Place-Name Society.

Harte, Jeremy, 2008, English Holy Wells: A guide (three volumes), Heart of Albion.

Nichols, John, 1795–1815, History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester (eight volumes).

Palmer, Roy, 1985, Folklore of Leicestershire and Rutland, Sycamore Press; revised edition 2002 Tempus.

Potter, Clive, 1985, ‘The holy wells of Leicestershire and Rutland’, Source 1st series viol.1: p15–17.

Potter, T.R., 1842, The History and Antiquities of Charnwood Forest, Hamilton Adams.

Rattue, James, 1993, ‘An inventory of ancient, holy and healing wells in Leicestershire’, TLAHS 67: 59–69; archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/browse/details.xhtml?recordId=3252619

Richardson, Linsdall R., 1931, Wells and springs of Leicestershire, HMSO.

Trubshaw, Bob, 1990, Holy Wells and Springs of Leicestershire and Rutland, Heart of Albion.

Background image: Ashwell's eponymous well in June 2009 (Photo by Bob Trubshaw)

Ashwell's eponymous well in June 2009 (Photo by Bob Trubshaw)