Wednesday 15 October 2025

George Stephenson and Leicestershire - a new look at the story of a ‘Great Man’

LAHS Vice President Robert Hartley explores the local connections of the ‘Father of Railways’ George Stephenson.

The railway engineer George Stephenson was one of the founders of the town of Coalville, and his role in creating the Snibston Colliery is famous. What is less well known is that his three brothers, James, Robert and John also have links to the town, which came to light during research into a new biography of Stephenson, his family, friends and assistants.

George Stephenson’s career spanned a wide area of Northern England and the North Midlands, as well as many months in Westminster explaining his schemes to Parliamentary committees. When he was engineer to the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in the late 1820s he lived in Liverpool, but as plans emerged for railways linking London with Birmingham and Lancashire, and with Derby, Leeds and York, he presumably wanted a more central base, which is how he came to live in Leicestershire.

His first recorded visit to the county was in February 1829. He had been invited to a meeting at the Old Bell Hotel on Humberstone Gate to establish a company to build a railway between Leicester and Swannington, on the north-west Leicestershire coalfield. He would subsequently invest in the company and join the committee, although the work of planning it and supervising its construction would fall to his son Robert.

George realised that once the railway was open it would transform the economic potential of the coalfield by conveying the coal efficiently to supply the businesses and households of Leicester. He subsequently took a lease of the Snibston estate with the idea of establishing a coal mine himself. Mining was, after all, the industry he had grown up in, and in 1830-1832 his other, much larger, railway schemes were all stalled owing to strong opposition in Parliament. For a while, coal mining may have seemed a more secure career, and coal was certainly in demand.

1832 also saw the arrival in Coalville of George’s older brother James, who had driven the Stockton & Darlington Railway's ‘Locomotive No 1’ for several years from after the line first opened in 1825.1

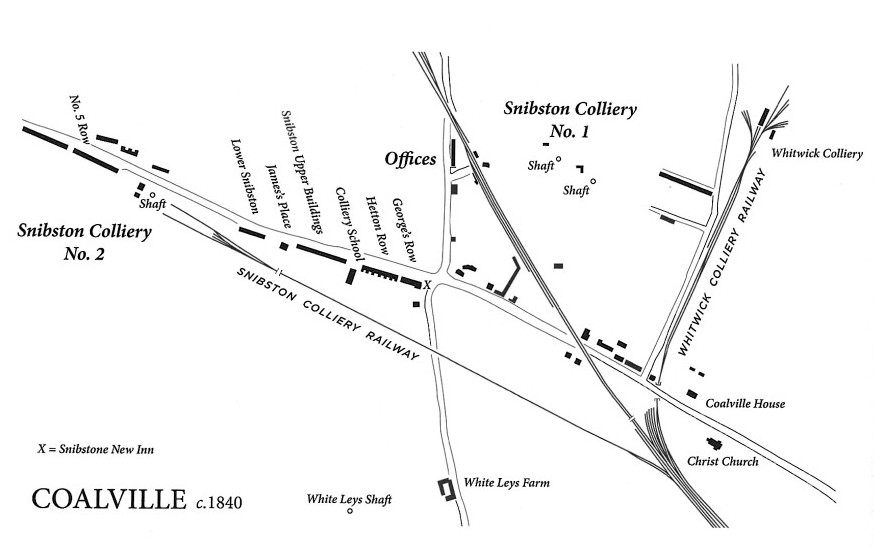

In February of that same year a group of workmen began preparations for sinking a mine shaft near White Leys Farm, about 400 yards SSE of the crossroads where today the Coalville Clock Tower stands. In charge were James Stephenson and Thomas Parker, both from Northumberland. James was George’s older brother, and Parker was an experienced miner.

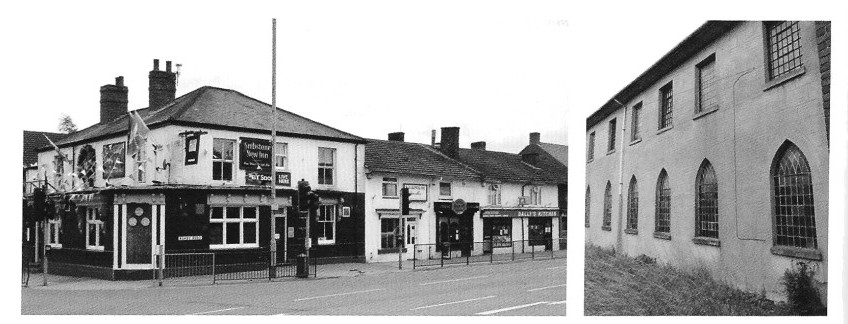

For reasons which are not recorded, the White Leys shaft was not developed, and instead the scene of operations was moved to a new site about 200 yards NW of the Coalville cross-roads, which would become the Snibston No.1 Colliery. We are fortunate in having the eyewitness account of Samuel Fisher, who arrived aged nine with his family, in 1832, and over the next few years witnessed the creation of the new community which would later be named ‘Coalville’. This was published by the Coalville 150 group in 1992.2 The “150 Group” itself had its origins in the celebration of the town’s 150th anniversary in 1983, when Denis Baker published his very well-researched history of the town.3

George Stephenson did some work in the summer of 1832 on behalf of the Leicester & Swannington Railway. He reported to the Board at the end of July with his views on the potential for extensions of the line beyond Swannington. Following on from this the Coleorton Railway was planned, to reach collieries at Peggs Green and at The Smoile at the northern tip of Coleorton parish. It is possible that he may also have realised that by using a unique form of iron rail, it would be possible to run standard-gauge railway waggons from the Coleorton Railway along the earlier "plateway" to the Cloud Hill limestone quarries.

In 1834 George Stephenson and his partners began to sink another mine shaft half a mile west of Snibston No.1. This was Snibston No.2, the colliery which would be a familiar part of the landscape of Coalville. It probably began to produce coal in October 1836, when the branch line from the Leicester & Swannington Railway was opened.

Coal mining continued at Snibston No.2 Colliery until 1985, after which the buildings were incorporated into the Snibston Discovery Park by the Leicestershire Museums Service.

The Stephensons in Coalville

James Stephenson soon started a new career as the “supervisor” of Snibston Colliery. Thomas Summerside, who knew all the Stephensons, suggests that George had done him a kindness in giving him this job. The Stephensons were a close-knit family who looked after one another.

James’s wife Jane died at about this time, perhaps as a result of complications with the birth of their daughter Eleanor in 1830. Despite this, James took his niece Ann into his household at Snibston. Ann was the daughter of the youngest Stephenson brother John, who was accidentally killed in 1831 whilst working in the engine works of Robert Stephenson & Co., in Newcastle. George continued to provide for them, and in 1833 he gave to “James Stephenson of Coalville… Engineer” ten shares in the Leicester & Swannington Railway, “in consideration of the natural love and affection which I have for and towards (him)..”

George Stephenson brought other assistants to work in various roles developing the colliery, including former employee James Campbell. James Stephenson had saved Campbell’s life on one occasion, when the man operating the winding engine failed to stop it as the cage containing Campbell came to the surface. Had James not acted swiftly to stop the winder, Campbell and the other men with him would have been thrown down the deep shaft to their deaths.

James Stephenson became a respected figure in the new community at Snibston. He and Jane had at least three daughters, one of whom, Elizabeth, was married in February 1836 to John Stenson, from the other local mine-owning family. In the notice of the occasion, her father is described as “James Stephenson of Coalville” and this is possibly the earliest mention of the new name for the little town.

James’s daughter Ellen or Eleanor died in the January of 1845, and James himself died on August 9th 1847. When the graveyard at Christ Church in Coalville was cleared of monuments in recent times, the memorial stones to both Ellen and James were rescued and put on display inside the church. Perhaps Coalville could make rather more of its association with “Engine Driver No.1” who lived here for nearly a quarter of his life.

The fourth Stephenson brother, Robert (known as Robert Senior to distinguish him from George’s son) is also, at one remove, associated with Coalville. When he died in 1837 his son, George Robert, was just 17 and still at school. He was George Stephenson’s oldest nephew and joined the family business of railway building. After the death of George’s own son Robert in 1857, George Robert inherited his share of the Snibston Colliery, becoming the senior partner there.

George Stephenson and Alton Grange

With his instinctive knack of thinking strategically, George Stephenson no doubt calculated that by living near to Snibston he would be well located to work on the railways being created between London, Chester and York. In fact, he was, whether consciously or not, following the Romans in their conquest of Britain.

Leicestershire lies just east of what was, in the 1820s, one of the best roads in the country - the old Watling Street, rebuilt as Telford’s Holyhead Road (better known to us as the A5) leading to Chester, North Wales, and Ireland. The main road from London to Manchester and Carlisle (later the A6) led through Leicester itself, while not far to the east was the Great North Road to Edinburgh. By some estimates, Lindley Hall near Hinckley is considered to be the centre of England.

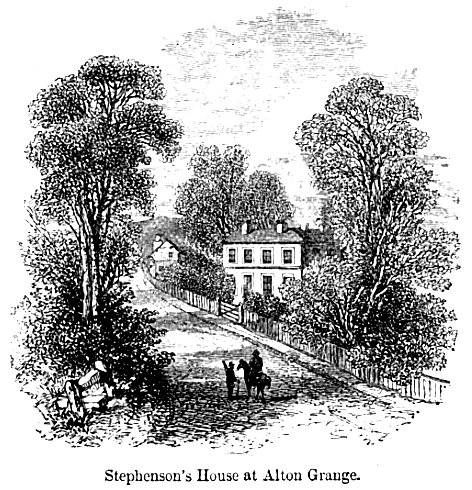

George clearly decided that this was a good place to base himself, and he could also keep an eye on the completion of the Leicester & Swannington Railway and the creation of Snibston Colliery. In the summer of 1832 he and his wife Betty moved to a handsome Georgian house at Alton Grange, halfway between Snibston and the market town of Ashby de la Zouch. The house still stands, and now bears a blue plaque in recognition of George Stephenson’s time here.

Based on the evidence of surviving correspondence, we know that Stephenson was in residence from at least August 1832 until September 1838. This was a period of incredible activity in the building of railways, including the ‘Railway Mania’ of 1835-1837.

The 1830s ‘Railway Mania’ and Alton Grange

In May 1833, the railway-building firm George Stephenson & Son was successful in gaining Parliamentary approval to build three railways - the London & Birmingham, the Grand Junction (Birmingham to Warrington) and the Whitby & Pickering, and work began on these lines. Initially, Stephenson had only planned the northern half of the Grand Junction, but he quickly resurveyed the southern half and took over construction of that as well.

The promoters of the London & Birmingham insisted that their line should be solely supervised by Robert Stephenson, and he should not take on any other work.

George, however, was always reluctant to turn away offers of work. A succession of wealthy financiers and young engineers made their way to Alton Grange for planning meetings, no doubt watched with interest by the residents of Ashby. In 1834-1836 he planned a chain of four magnificent railways from Birmingham to Derby, Sheffield, Rotherham, Leeds and York. They were all fortunate in gaining approval from Parliament at the first attempt, and construction began quickly. He and Robert took new London offices at 16, Duke Street, Westminster. He also planned a railway from London to Blackwall, linking the heart of the City to the new docks where ships departed for Britain’s growing Empire in India and in the Caribbean Islands.

As if this were not enough, during 1836 and 1837 Stephenson also planned railways from Rugby to Stoke on Trent and Manchester, Stoke to Chester and Birkenhead, and Manchester to Leeds. The first of these faced huge opposition, ironically from Stephenson’s erstwhile employers the Grand Junction Railway. The Chester & Birkenhead and the Manchester & Leeds went ahead quickly, but the other lines would be the subject of protracted struggles in Parliament for several years.

The many problems involved in getting these schemes authorised can be seen in incident which took place in Leicester. All railway plans had to be deposited with the Clerks of the Peace (who would record the exact time of delivery) before midnight on November 30th to be considered in the following year’s debates. The original plans for the Tamworth to Rugby section happened to cut across the county boundary for a few yards into the parish of Sheepy Magna.

As only one field in Leicestershire was affected the surveyors may have failed to notice this until the last moment, when they were hastily dispatched to the Clerk of the Peace for Leicestershire, William Freer. We may imagine the scene as the messenger knocked on his door in Leicester and handed over the rolled-up plans and Books of Reference for the entire line. Freer looked at his clock, and noted down the time of delivery as being “on the 1st of December 1836 at seven minutes past twelve a.m.”!

Very likely on this technicality the plans were rejected by the Parliamentary committee the following year,4 although much of his route from Rugby to Stoke on Trent was eventually built.

George Stephenson left Alton Grange in the Autumn of 1838, for the much larger Tapton House near Chesterfield. Despite his departure Stephenson still returned to Leicestershire for work, and went on to plan the line from Syston to Peterborough via Melton Mowbray.

Robert Hartley is the author of ‘The Master of these Marvels - George Stephenson and his Circle of Genius,’ Published by the Railway & Canal Historical Society. £30. The publication of this book was supported by a grant from the LAHS.

If you enjoyed this blog, why not explore our other blogs about the history of Leicestershire and Rutland here.

Notes

1 Bailey, M R & Davidson, P H, 2025, "Locomotion No.1- the True Story of the World's First Public Service Locomotive".

2 Fisher, Samuel, 1992 “Reminiscences of Early Coalville”, Coalville 150 Group.

3 Baker, Denis, 1983 “Coalville - the first seventy-five years”, Leicestershire Libraries and Information.

4 ROLLR, Ref. QS/73/18 The plans are signed by George Stephenson and Charles Liddell.

1883 map showing Coalville. (Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland)