Sunday 17 December 2023

George Hort ‘Leicester’s Forgotten Working-class Hero’ 1783 – 1858

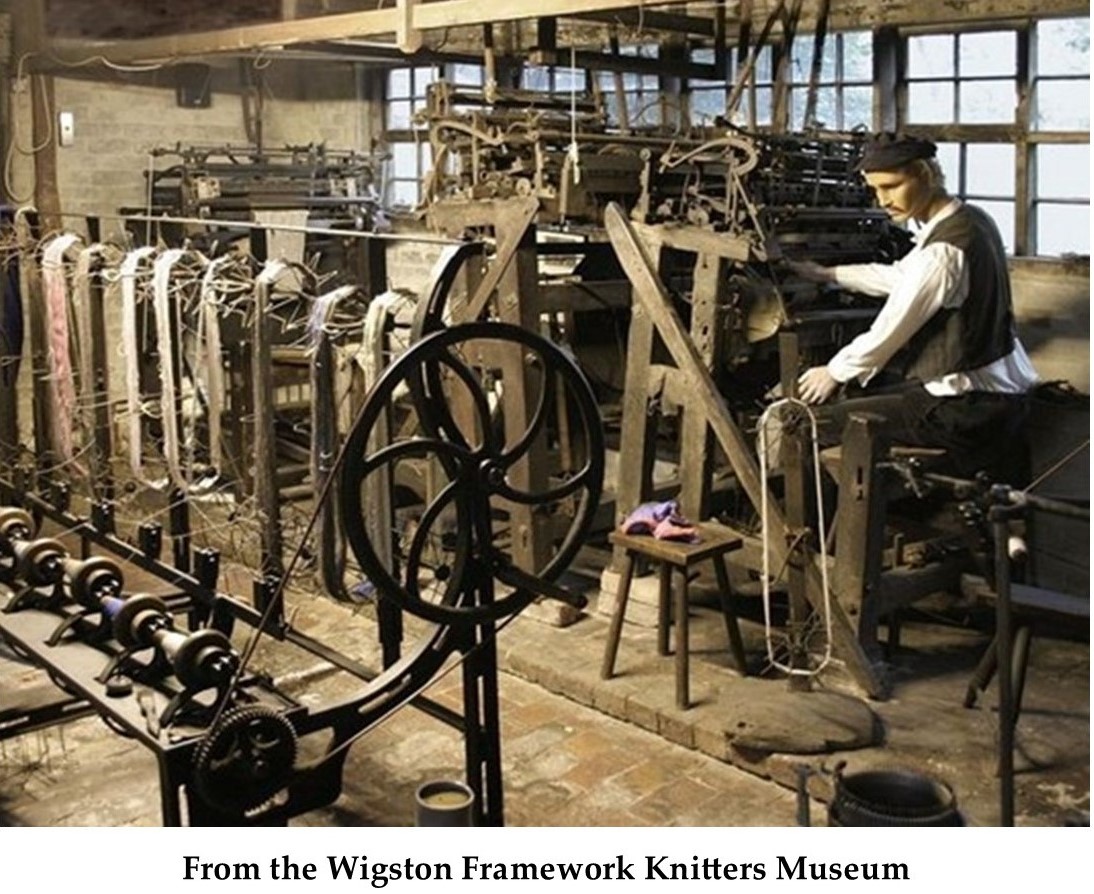

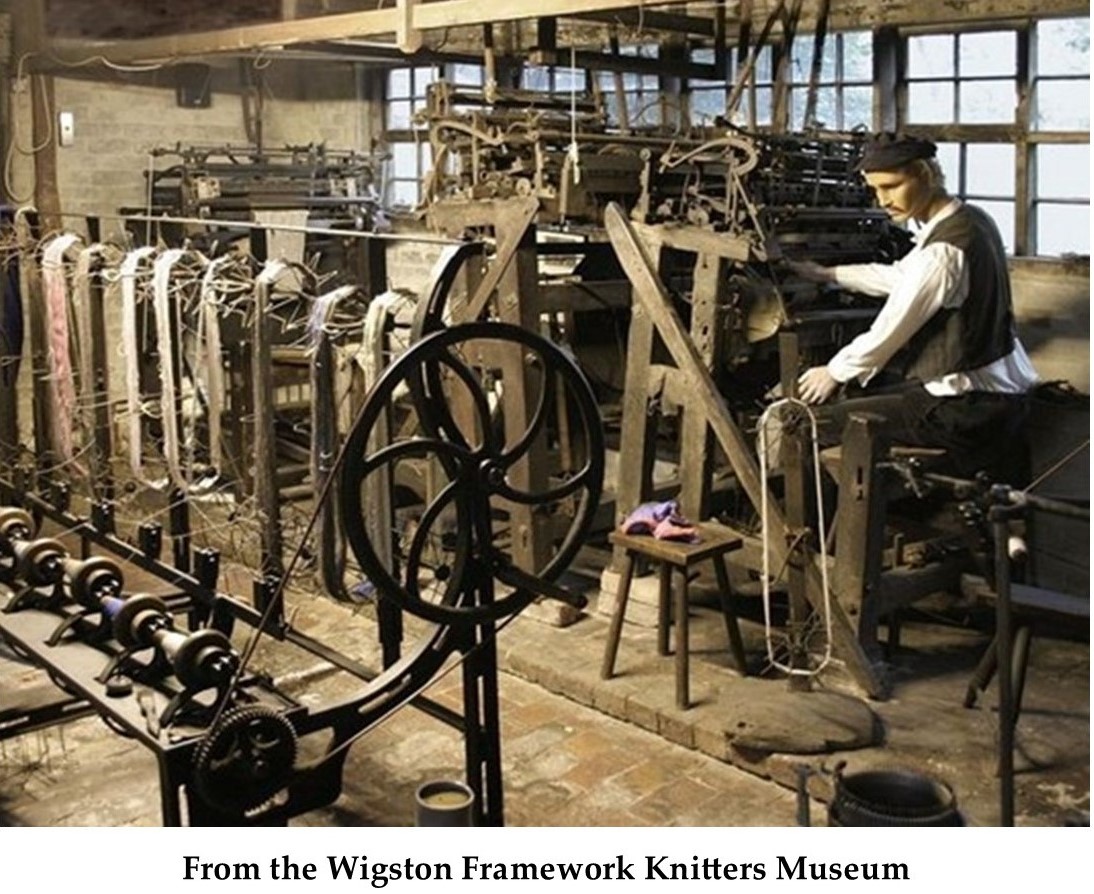

Steve Marquis, LAHS member and author of a recent new book on the Framework Knitters of Leicestershire, discusses here the life of an early 19th Century prominent leader of the Leicester Framework Knitters Union.

GEORGE HORT was born in the St. Margaret’s area of Leicester on 17 January 1783. He would spend the rest of his life as a largely impoverished stockinger but also as an intrepid fighter for the town’s framework knitters and other poor working people over four decades. During this period, Hort was one of the foremost leaders of the Leicester Framework Knitters Union which had emerged in 1817, in fact, from 1824 until 1830, the dominant figure during the union’s most militant phase. It must be remembered that framework knitters made up almost 50% of Leicestershire workforce at this time.

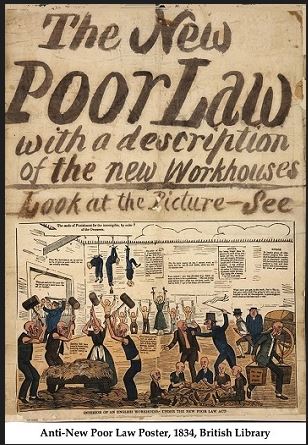

He also led two of the most significant and desperate campaigns undertaken by Leicester’s working people during this time: the fight against the 1834 New Poor Law and the union’s attempt to finally eradicate the ‘truck system’. And yet, I suspect very few readers of this piece would have heard of George Hort. He doesn’t even make it onto Ned Newitt’s exhaustive list of Leicester Radicals.

I first came across the name of George Hort whilst researching my book (see below).His name appeared regularly in the local press from 1824 until well into the 1850’s, (interestingly, he gets a far more hostile coverage than any other working-class leader, including Thomas Cooper) but barely gets a mention in the two most significant histories of this period, Radical Leicester by A, Temple Patterson (1954) and J. F. C. Harrison’s Chartism in Leicester (1959). In Patterson’s case, I would contend this reflected his own prejudices rather than Hort’s relative importance. His treatment of Thomas Cooper and Hort’s close associate, Thomas Wright, reinforces the view that he was hostile to the more left-wing and militant of Leicester’s working-class leaders.

Hort made his first public appearance in 1824 when he emerged as the new leader of a reconstructed Leicester Framework Knitters Union after two disastrous years which had destroyed its predecessor. In choosing Hort, the membership appeared to be looking for a more belligerent approach. And this is what they would get for the next six years. He was sentenced to six weeks hard labour in 1825 for leading an attack on William Thompson’s frame shop in Newton Harcourt (a neighbouring village to Wigston), when Thompson tried to restart his frames during a strike. After six years of bitter industrial disputes which were mostly lost, Hort’s leadership came to an end following yet another defeated strike, although it seems he remained a member of the union’s ruling council.

After losing the leadership of the Framework Knitters Union he appears to have remained on the ruling council almost for the rest of his life and according to newspaper reports continued to be active in fighting for the knitters on several fronts. Very quickly after Hort’s fall from grace following the disasters of 1830, the knitters' union had once again virtually ceased to exist but began to revive in 1832 as part of the massive national upsurge in trade union membership during the major industrial troubles of 1832-34.According to a report in the Leicester Herald( 9/1/1833), Hort, along with Thomas Wright had clearly played a crucial role in rejuvenating the union during those two years.

Other newspaper reports from this period revealed another side to George Hort’s character. He was apparently a regular drinker in pubs around the Magazine area. When three constables arrested four men outside the Angel Inn, in Oxford Street, at 2 am on Sunday 22 June 1833, Hort is reported to have led a hostile crowd who threatened the arresting officers, calling them “villainous tyrants and ravenous bloodsuckers” (Leicester Chronicle, 28 June).A few months later Hort appeared in court as a witness in what turned out to be the murder of Charles Fewkes, who after a drunken brawl, again at the Angel Inn (now student accommodations), turned up later in the river dead. Three men were found guilty of Fewkes’s manslaughter, and the landlady of the Angel Inn admonished for keeping a disreputable house (Leicester Chronicle, 24/8/1833).The Leicester Chronicle (29/7/1836)also reported that Hort was assaulted in the Peacock Inn by a Soloman Thompson after he had accused him of being a police informer. Thompson was fined 10s.

However, it was during the anti-Poor Law campaigns of 1836-38 that we see the return of George Hort the class warrior. He now appears regularly in the local press attacking Liberals at meetings for their betrayals of the 1832 Great Reform Act and the pernicious treatment of the poor as a result of the 1834 New Poor Law or representing individuals at Board of Guardians tribunals and in the magistrates’ courts.

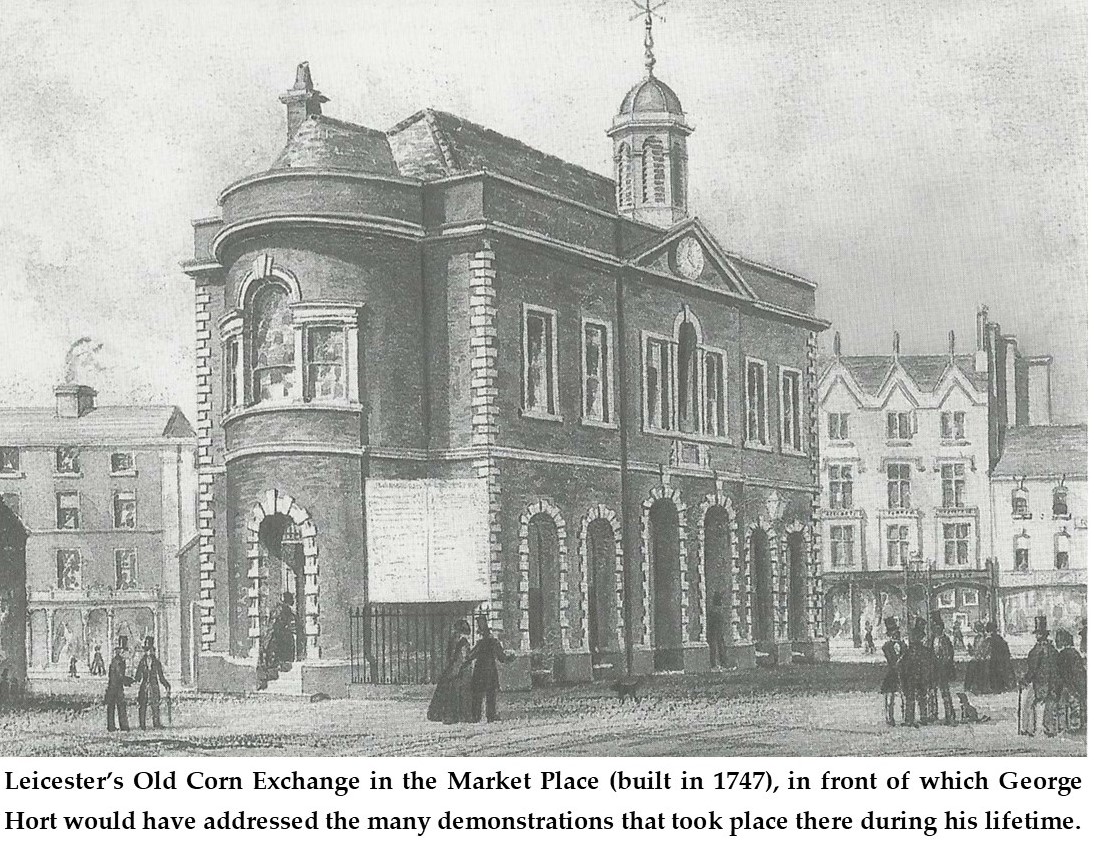

At a public meeting on Monday 21 June 1836 to discuss a petition – intended to be sent to the “King in Council” – against the practice of separating husbands and wives on entry into a workhouse – George Hort proposed the motion supporting the petition making a long speech which was surprisingly fully reported in the Leicester Chronicle(25/6/1836)– the full speech appears in an appendix to my book. This is really the only time we get to hear the authentic voice of George Hort’s, a voice revealing the ability and confidence to rise above the limitations of his birth that would normally condemn him to a life of servility. Just another example of many working-class leaders of this period who with very little or no formal schooling managed through sheer determination even after long hours of gruelling manual work, to self-educate themselves to extraordinary levels by reading borrowed (or stolen) books in candlelight.

Over the next two years Hort attended numerous public meetings, often organised by the Town’s ruling Liberals, and no matter what the agenda, he would condemn their treatment of the poor at every level of national and local government, especially the cruel indifference shown by Boards of Guardians of the new workhouses (Leicester Chronicle, 8/8/1837; 17 and 24 February 1838; 10/3/1838; Leicester Journal,20/5/1838).

Local newspapers also included frequent reports of Hort representing destitute people in their desperate attempts to challenge their appalling treatment by Guardians and magistrates, including refusing entry to sick or starving people into the workhouse because they were not permanently resident in the town. On one such occasion the man was so ill Hort let him stay with him for three days (Leicester Mercury, 10/11/1838).

For these efforts Hort was seen as an upstart and often met with condensation, even abuse, in the local press, here are some examples: -

“…whose virtuous disclaimers upon the hardship of conjugal and parental separations. We are unsure whether this individual [Hort] is considered the delegated representative of the working-classes – or whether the manifestoes alluded to, are the offspring of his fruitful brain.”(Leicester Chronicle, 9/6/1838).

“… your [Hort] conduct was disgraceful.” (Leicester Chronicle, 4/3/1837)

“…wolf in sheep’s clothing” (Leicester Chronicle,3/3/1838).

“… industrious perverter of the truth” (Leicester Chronicle, 10/3/1838).

These rebukes may seem remarkably tame by today’s media standards (one shudders at the abuse he would get in the likes of today’s Daily Mail) but the local press in the first half of the 19th century was effusively polite, especially to establishment figures, but other working-class leaders like John Markham, even Thomas Cooper, never received the same level of negative personal criticism heaped upon George Hort.

Although Hort still appears in the newspapers fairly regularly through the 1840s, surprisingly, his name is never linked to Chartism or Chartist activities, nor is he mentioned in Thomas Cooper’s autobiography. It also explains why he didn’t appear in Harrison’s book. This is very puzzling, Hort was still a leading member of the knitters’ union, yet apparently took no active part in some of the most dramatic events and the most important political campaign the stockingers were ever involved in. I can only speculate that he concentrated instead on representing individual workers in the various tribunals.

His first appearance in the local papers during this decade was in the Leicester Mercury on 26 February 1842, which included a statement by Hort denying the accusation in the Leicester Journal(25 February) that he played any part in making the effigy of Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, or in the Market Place protest where it was burnt. This action was part of nationwide protests organised by the Anti-Corn Law League on 19 February, in which Peel’s effigy was burnt in many industrial towns.

The issue that did dominate Hort’s activities during this period was the use of ‘truck’ by some hosiery employers to pay their workers in goods rather than money, even though it had been illegal to do since 1831. Three letters by him appeared where he attacked free trade in general and the truck system in particular (Leicester Mercury, 30/9/1843;17/2/1844 and 5/2/1848). These letters, like his speech which appeared in the Leicester Chronicle on 25 June 1836, show just how articulate and accomplished, both in written word and speech, Hort was. His letters are remarkably succinct, well written and argued and contain none of the elaborate verbosity common in that era.

There are also accounts of Hort successfully taking employers to court for paying truck, including a Mr Knight, one of the largest hose manufacturers in Leicester with 500 frames who paid his workers half their wages in bread, and John Cave, who was fined £5 or six weeks in prison, again for paying part of his workers’ wages in bread. In a letter published in the Leicester Mercury (9/12/1843), Hort reveals that he had managed to setup a joint committee of more progressive employers, including William Biggs, and the Framework Knitters Union to tackle any continued use of the illegal truck system.

George Hort appeared in all the local newspapers during March of 1849.Now in his mid-fifties he was clearly the driving force behind a strike of enraged sock workers in the Loughborough area which lasted for several weeks and included incidents of window breaking and attacks on factories still working.

His very last appearance was in the Leicester Mercury on the 4 June 1853, where he wrote one final letter outlining the many difficulties still faced by framework knitters and appealed for them to get a better deal. He died in January 1858 aged 71 and was buried in Welford Road Cemetery.

I believe it is time for his memory to be resurrected and his contribution to the building of Leicester’s labour movement at last recognised.

Steve Marquis.

My book includes the only detailed account of George Hort’s life.

Illustration of 19th Century Framework Knitter at work provided by the Wigston Framework Knitters Museum