Sunday 16 June 2024

‘Almost an Englishman’ – a French refugee and his family in Leicester

LAHS Newsletter Editor, Cynthia Brown presents the life of Charles Camille Caillard, a French nobleman who made his home in 19th Century Leicester

The name of Charles Camille Caillard may be familiar to some readers as a leading member of the Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society, serving as its President in 1855 – 56 in recognition of the fact that Britain and France were at that time ‘united in arms’ in the Crimean War. He lived in Leicester from 1838 until his death in 1873, working as a Professor of Modern Languages and playing a prominent part in local social life. Little is known about his wife Mary apart from her birthplace in Walworth, Surrey, her occasional involvement in a social event, and her death in Leicester in 1882. However, their three children, Mary Sophia, Ernest and Alfred, led interesting lives in their own right, repaying a close look at the family.

.jpg)

Charles Camille Caillard was born in Paris around 1805 and attended the College Charlemagne there. As a chevalier, a member of the French nobility, he came to Britain as a refugee after fighting in the July Revolution of 1830 that brought the ‘Citizen King’ Louis Philippe to power. The date of his marriage to Mary is unclear, but Mary Sophia was born around 1838 in London. In the summer of that year the family moved to Leicester, where Charles Caillard was introduced by his compatriot Monsieur De Rudelle in the Leicester Journal as his successor as a Professor of Languages, a not unusual occupation for refugees needing to make a living. He was described as ‘a native of Paris, lately from London, who is in every respect capable of giving entire satisfaction as to his ability… and his private character as a Gentleman’.

In February 1839, when the family were living in Nelson Street, off London Road, he was offering separate classes for ladies and gentlemen at a cost of one guinea (21s) a quarter, in conjunction with M. Philarete Horeau, a Professor of Languages of London Road. An advertisement in the Leicestershire Mercury promised that the ‘usual course of Studies will occasionally be relieved, by Conversations, Readings, and Lectures’. M. Horeau later moved to London, leaving Charles Caillard as the sole resident Professor of Languages in Leicester. As such, he stated in a notice of a change of address to Newtown Street in 1849, ‘he is enabled to give TWO LESSONS a week, which effectually reduces his terms to half those of a non-resident’. In addition to private lessons, he was Professor of the French Language at the Collegiate School in Leicester and taught French at Belmont House School for girls.

French was a desirable ‘refinement’ among the Victorian middle classes, and of wider practical use as opportunities for foreign travel expanded. However, much of Charles Caillard’s attention focused on its value in terms of trade and commerce. In 1860 he published The French Correspondent, ‘containing every necessary instruction for writing letters in French’. In 1872 he wrote that manufacturers ‘who desire to extend their transactions throughout Europe, will find it hereafter a necessity to speak and write French, should they travel, or need to correspond on commercial subjects with customers abroad’. For a fee of 8s a quarter he offered courses at different levels ‘to afford opportunities to every class of the inhabitants of Leicester to acquire this valuable accomplishment’. The Elementary Class concentrated on pronunciation, ‘properly conveyed by a native of France’. The next level, ‘principally intended for young men in business’, aimed to ‘enable the learners to read easily French handwriting, and translate, and answer French letters’, while fluent conversation was the focus of the highest level.

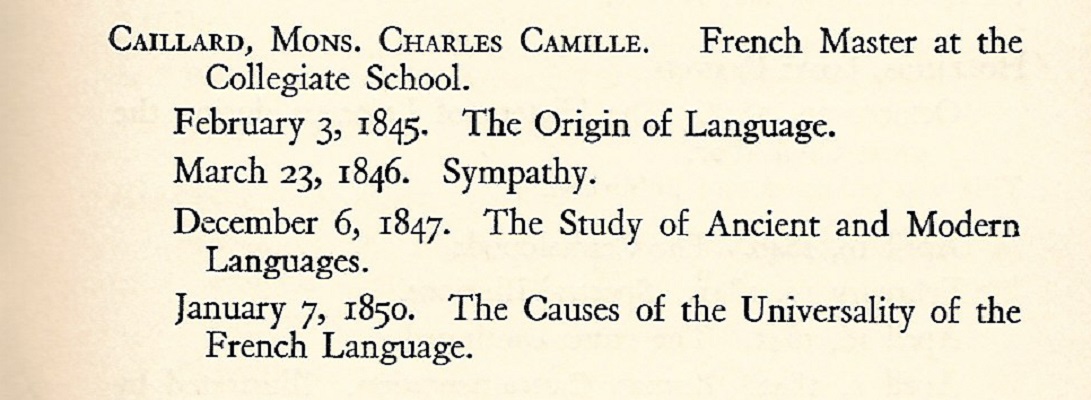

Charles Caillard’s involvement with the Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society began a few years after he came to Leicester. In February 1845 the Leicester Journal described him as ‘comparatively a new member’, but he became a very active one, organising musical and theatrical events, often with a French theme, and giving lectures or commenting on those delivered by others. In January 1853, for instance, he gave a lecture on ‘The writings of Berenger’, the French poet and writer of popular songs; and another on ‘French prose and fiction’ in 1861 in which he argued that ‘French literature, and more especially that of novel writing, did not deserve the reproach of immorality with which it was branded in this country…’.

He was known for his ‘outspoken frankness’. In November 1854, on the subject of classical education, he argued that ‘too much prominence was given to it in England, and too much time wasted upon it’. Commenting on a lecture by another member in 1863, he described the American poet and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson as ‘among other poets whose mannerism and intensified style brought upon the reader a state of somnolence or nervous agitation’. He was also the first member of the Lit and Phil to suggest the inclusion of ‘lady members’. That did not happen in his lifetime, but with ‘that gallantry belonging to his nation, he had ever expressed the rights of ladies’.

Charles Caillard was also instrumental in founding ‘The Club’, established by a group of gentlemen ‘differing greatly in character and opinions’ following a supper party after a Lit and Phil lecture in May 1860. There is no suggestion here or elsewhere of his own political inclinations, but ‘The Club’ met regularly in members’ homes to express their views, with ‘no limit other than that prescribed by good taste’, based on friendship that was ‘proof against all outdoor quarrels’. He was its only member of ‘foreign blood’, but took pride in being French and never felt the need to seek naturalisation as a British citizen. While ‘doing so much to render Leicester familiar with the language and the literature of his native land’, as the Leicestershire Mercury noted in 1859: he ‘has happily become almost an Englishman, still retaining all the polish and other fine traits of La Belle France’. On his death in Leicester in 1873 he was recalled as a man of:

‘remarkable social qualities… He possessed the enviable secret of winning respect and regard. There was something about him reminding one of the politeness of the old Noblesse school, mingled with the outspoken frankness of the new; and, while surrounded with all that was thoroughly British to the core, it was his pride to be true to his nationality’.

He was buried in Welford Road Cemetery in Leicester, as was his wife Mary when she died in 1882, and later their eldest child Mary Sophia. The family had moved to 85 Welford Road in 1861, and by 1873 Mary Sophia was evidently continuing her father’s work, advertising herself at that address as a Professor of Languages offering tuition in ‘French, English (Grammar and Analysis), German. Italian. Spanish and Latin’. In 1874 she was listed among the members of a local committee supporting a campaign for votes for women who were householders and ratepayers, being qualified in both respects - but in a letter to the Leicester Chronicle soon afterwards she described this as ‘a misunderstanding’:

‘No one was more startled than myself to see it there, and I feel it would be absurd to allow myself to be represented as taking a prominent part in a movement about which I have not even, at present, formed a deliberate opinion in my own mind. I will even candidly confess that, in my present utterly harmless state of feminine ignorance of politics, a vote would be a most embarrassing addition to my “Rights”…’

A ’feminine ignorance of politics’ was a common enough state at that time, and perhaps one more conducive to business as a language teacher than public activism; but around 1890 Mary Sophia embarked on a very acceptable activity for an unmarried middle class woman by establishing an Evening Home for Boys in premises off King Street. This offered ‘useful and instructive amusement and drill… to train them in habits of obedience and steady regular work’. It also provided entertainments and lectures, chess and draughts, music and recitations, and a gymnasium, along with two football clubs, a summer cricket club, and a unit of the Boys’ Brigade.

‘All this means much work’, as one report put it in 1895, and not always with success. There were inevitably instances of ‘mutinous behaviour’ and ‘backsliding’, and ‘a few have had to be given up, as they have deliberately preferred dirt, idleness and poverty, to work and cleanliness’. The Home relied heavily on subscribers and fundraising events by the boys, such as a ‘Grand Gymnastic Display’ in 1899, and its finances were often a cause of concern. Even so, there was said to be ‘much reward in the shape of the personal delight of making upright, well-conducted men, out of material which promised to develop into vulgarity and vice’. The Home continued for some years after Mary Sophia died in 1895, leaving effects of £903 12s. 3d.

Her brothers Ernest and Alfred were born in Leicester in 1840 and 1841 respectively. Both attended the Collegiate School, and both served in the Leicester Rifle Corps of the British Volunteer Force, formed in 1859 following the perceived threat of a French invasion. In the 1861 Census Ernest is identified as a clerk for the Leicester Gas Company. This was taken over in 1878 by the Borough Corporation, and by 1891 he had risen to the position of Chief Clerk. When he retired in 1901 after 47 years’ service, it was said that ‘he had never been known to make an enemy or to say or do anything either unkind or uncharitable’, and he was he was presented with a testimonial, a gold pencil case and a purse of gold. He moved soon afterwards to Southport where he lived for some time before his death in 1928 at the age of 87.

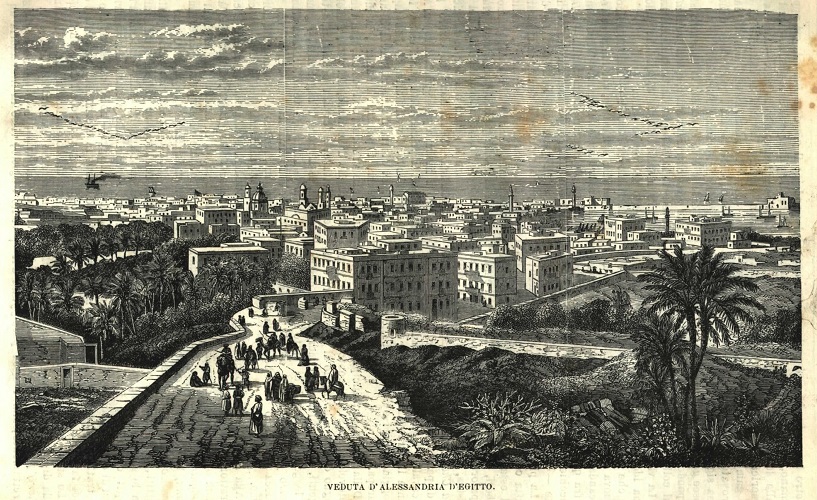

The sudden death of Alfred Caillard in 1900 after some years of failing health was widely reported well beyond Leicester itself - from Alexandria in Egypt, where he had been employed in various capacities for around 25 years. After leaving the Collegiate School he attended the Lycee Louis le Grond in Paris. In the 1861 Census he is listed as a hosier’s clerk, but entered the Civil Service Post-office Department in 1863. Alfred was the only one of the siblings to marry – to Edith Elizabeth May, daughter of the late William Henry May MRCS of St Martin’s, Leicester - in Eastbourne in 1868. In the 1871 Census, shortly after the birth of their first child Edith Mabel, he is described as ‘Civil Service (1 Class) Receiver of Accountant-General’s Office, General Post Office’.

In 1875, in response to a request to the GPO by Ismail Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt, for assistance in reorganising the Egyptian Postal Administration, he was appointed as Financial Controller of the Egyptian Office. He became Postmaster-General of Egypt in the following year, administrator of the Khedivieh Mail Steamship Service in 1878, and Director-General of Customs (Egypt) two years later. He was also an ex-officio director of the Alexandria Water Company. Described as ‘an absolutely up-right, honourable, and devoted public servant’, his work attracted many awards including that of Commander of the Austrian Order of Franz Josef, Commander of the Hellenic Order of the Redeemer (Greece), and decorations for services in Egypt for assistance in negotiating commercial conventions. He was appointed a Commander of the Order of St Michael and St John by the British government in 1890, and a Pasha – a title conferred on high officials - by the Khedive of Egypt in 1899. He left effects of £2199 19s, and was buried in Ocklynge Cemetery in Eastbourne.

So ends this account of Charles Camille Caillard and his family – whose name, we are told, was often pronounced in Leicester as ‘Calliard’, as it ‘then came more easily to the lips’, but whose contributions to the life of the town, and in the case of Alfred far beyond, perhaps deserve to be a little better known.

Cynthia Brown, June 2024

Sources

Census returns

England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1995

Newspapers – various dates: Hinckley Times; Leicester Chronicle; Leicester Daily Post; Leicester Daily Mercury; Leicester Guardian; Leicester Journal; Leicestershire Mercury

Spencers’ Illustrated Leicester Almanac, 1895

Debrett’s Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, 1893 available here.

F.B. Lott, The Centenary Book of the Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society, W. Thornley & Son, 1935

Caroline Wessel, Exchanging Ideas Dispassionately and without Animosity, Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society, 2010

In 1935 Afred Caillard’s eldest daughter Edith Mabel published a memoir under the name of Mabel Caillard entitled A Lifetime in Egypt, 1876 – 1935 (G. Richards, 1935). This is no longer available, but there is an extract at here.

The Collegiate School, Leicester, where Charles Caillard was Professor of the French Language. (Source The Midland Counties' Railway Companion. Wikimedia Commons, Public domain.)