Sunday 29 September 2024

A Wife’s Dilemma: Debt and The Married Women’s Property Act

LAHS Member Dave Fogg Postles presents a case study from Victorian Loughborough exploring an aspect of the impact of this Act.

In 1889, Sarah Ann Brinsley passed away. Administration of her estate (her goods, money and belongings) was granted not to her husband (as was usual when married women failed to make a will), but to Elizabeth Wells, ‘A Creditor.’ Sarah Ann was at her death the wife of William Brinsley, of Swannington. Elizabeth Wells was at the time the wife of Henry Wells, of Herrick Road, Loughborough, and so described in the grant of administration. The value of Sarah Ann’s estate was considered to be £90.[1]

The first section below explores the narrative of the relationships; in the second part, the context is explained. What is significant is the change in married women’s rights to personal estate (property as goods, chattels and money) in the late nineteenth century.

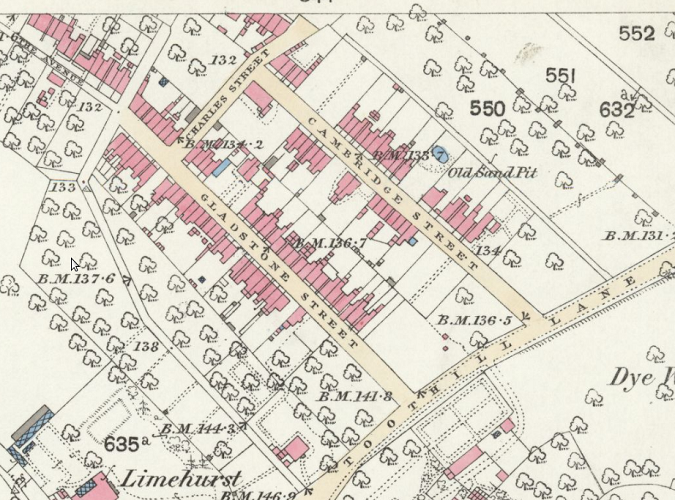

Sarah Ann Fisher was baptised at All Saints in Loughborough on 25 August 1841, the daughter of a plumber and glazier.[2] Her father, William Fisher, died on 17 September 1872, having composed his will four days previously. Although a craftsman, he placed his mark on his will. His personal estate was evaluated at under £450 (before 1881, estate was described as under a certain amount by increments; the preceding increment was £300, so his possessions amounted to between £301 and £449).[3] Just before his demise, his household was established (with the business) in Church Gate in Loughborough. At that point, Sarah, the eldest child, aged 29, was occupied as a milliner.[4] By 1881, Elizabeth, his widow, had moved the family to 47, Gladstone Street. Unfortunately, Sarah Ann was now described as ‘Domestic servant unemployed’, still unmarried and aged 39.[5] It was four years later that Sarah Ann espoused William Brinsley, a widower, of Swannington, a builder.[6] The marriage was short, for Sarah Ann died in 1889, aged 49, and was interred in the parish churchyard of St George, Whitwick with Swannington.[7] Whereupon, Brinsley embarked on another espousal, marrying Ann Lakin, a widow, also of Swannington, in November 1889, just half a year after the demise of Sarah Ann.[8] When Brinsley departed this life on 1 June 1895, his ‘effects’ (personal estate) amounted to no more than £59 1s 6d, to be managed by the executors in his will, William Bailey, underviewer, and Samuel Hallam, licensed victualler.[9]

Turning now to Elizabeth Wells, she was the wife of Henry, a hosier of Loughborough, inhabiting Gladstone Street in 1881. Described as a ‘Hosier’s wife,’ she was then aged 29, her husband, Henry, a year younger.[10] No doubt it was at this time that Sarah Ann and Elizabeth came into contact as neighbours, when Sarah Ann’s fortunes were at their worst. By 1891, Henry and Elizabeth had migrated to Herrick Road, he a hosier’s manager, but she was assigned no occupation by the census enumerator.[11]

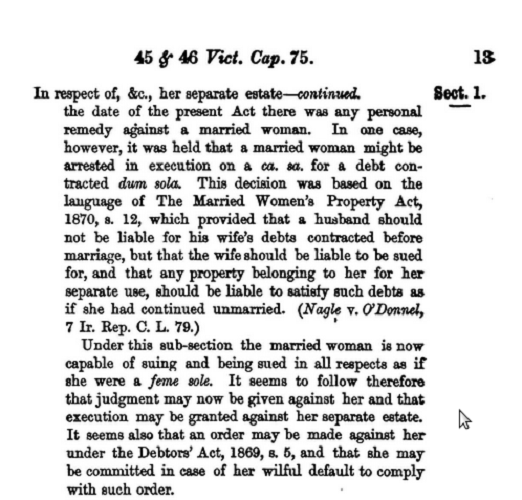

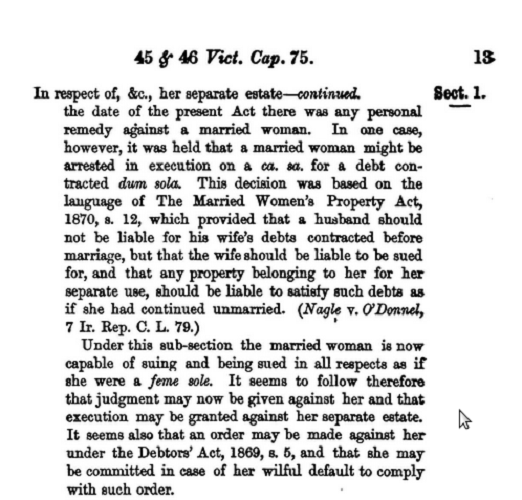

The important point is that when Sarah Ann and Brinsley married, she remained responsible for debts which she had contracted before their espousal and that she retained that personal estate which she had brought into the union. The persistent doctrine of couverture had prescribed that the husband acquired control over the whole household economy, with exceptions through marriage settlements (pre-nuptial arrangements) and the notion of paraphernalia (the limited items which a wife brought with her). Husbands had sometimes managed to avoid the obligations of their wife’s debt. The Married Women’s Property Acts changed the situation. Dissatisfaction with current arrangements had become manifest by the middle of the nineteenth century. Indeed, a bill had been introduced into Parliament in 1868. Those property changes were finally accomplished by the 1870 and 1882 Married Women’s Property Acts (33 & 34 Vict c. 93 and 45 & 46 Vict c. 75).[12] The former allowed married women to retain control over personal effects which they ‘earned’ or acquired during the time of their marriage while the latter extended their control over all their possessions, at least in law. (It was not until The Married Women’s Property Act of 1964 (UK General Public Acts 1964 c. 19) that the husband and wife became jointly invested in the household economy and wives became able in law to enter into credit relationships on their own).

The upshot was, then, that the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882 allowed Sarah Ann to retain control of her own goods, chattels, and money, but consequentially that estate was forfeited at her death to redeem her earlier debts.

Dave Fogg Postles

Notes

Note: according to the TNA Currency Converter, £90 in 1890 would be the equivalent of £7,384 in 2017.

This short piece derives from a wider examination of the effects of the Married Women’s Property Acts, currently being undertaken by the author.

Further Reading

Teresa Phipps, Medieval Women and Urban Justice: Commerce, Crime and Community in England, 1300-1500 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), pp. 64-79 .

Amy Erickson, Women and Property in Early Modern England (London: Routledge, 1993).

Susan Staves, Married Women’s Separate Property in England, 1660-1833 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990).

Lee Holcombe, Wives and Property: Reform of the Married Women’s Property Acts in Nineteenth-century England (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982).

Mary Beth Combs, ‘”A measure of legal independence”: the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act and the portfolio allocations of British wives’, Journal of Economic History 65 (2005), pp. 1028-1057.

Mary Shanley, Feminism, Marriage and the Law in Victorian England, 1850-1895 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989); for the ideological foundations, Donna Dickenson, Property, Women and Politics (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1997), pp. 79-91.

Footnotes

[1] National Probate Calendar (NPC) 1889 Bianchi-Bywater, p. 247.

[2] Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland (ROLLR) DE667/9, p. 78 (no. 619).

[3] ROLLR DE462/15, pp. 763-764.

[4] The National; Archives (TNA) RG10/3256, fo. 8.

[5] TNA RG11/3145, fo. 20.

[6] ROLLR DE667 All Saints marriage register p. 98 (no. 195); Whitwick (Swannington) banns book p. 6 (no. 28).

[7] ROLLR DE1260 Whitwick burial register, p. 56.

[8] ROLLR Whitwick banns book p. 12 (no. 59) (November 1889).

[9] NPC 1895 Aaron-Bywater, p. 282.

[10] TNA RG11/3245, fo. 15.

[11] TNA RG12/2516, fo. 70.

[12] For the earlier legislation in the United States, Patricia Lucie, ‘Marriage and law reform in nineteenth-century America’ in Elizabeth Craik (ed.), Marriage and Property: Women and Marital Customs in History (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press), pp. 138-58, at p. 146.

Alexander MacMorran, The Married Women’s Property Act, 1882 (London: Shaw & Sons, 1883), p. 13.)