Sunday 24 November 2024

A Walk Through Leicester. Susanna Watts (1768 – 1842)

Guest blogger, John Parker, retraces the footsteps of Susanna Watts. Abolitionist, author, translator, and artist.

Life and Background

Susanna Watts was born in Danet’s Hall, Leicester in 1768. The Hall was on manor land originally held by the earls of Leicester, however the ownership of the manor itself is not clear before 1428, when it was held by Richard Danet. The Danet family continued to be lords of the manor until at least 1647. Subsequently, the manor came into the hands of a family called Charlton, who were descended from the Danet’s. About 1700 the manor was acquired by the Watts family, who held it until 1769 then it appears to have changed hands repeatedly. (“The ancient borough: Bromkinsthorpe | British History Online”) In 1804 it was bought by Dr. Edward Alexander, on whose death, in 1825, it came to Elizabeth Kershaw, and subsequently to the Liberal M.P. Dr. Joseph Noble, it was sold in 1861 to the Leicester Freehold Land Society for building. Danet’s Hall was in the area north of Glenfield Road East and east of Fosse Road North in the LE3 5RJ postcode area. The Pub History Project website shows a pub called Dannetts Hall or Dannetts Hall Tavern which stood on the corner of Dannett Street, the name of the pub apparently referring to the old mansion that stood on the site.

She was the only one of the children of John and Joan Watts to survive childhood, her three elder sisters having died of consumption. Her father died when she was a baby and the family was then supported by her uncle whose death, when she was 15 years old, left the family impoverished. In her teenage years, to augment the family income and later to support herself, she taught herself French and Italian and among her early works are translations of Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered and Count Verri’s Roman Nights: Or the Tomb of the Scipios translated from Italian in 1802-03.

By the time Watts published Original Poems, and Translations in 1802 she already had a substantial reputation and was included in Mary Pilkington’s Memoirs of Celebrated Female Characters where she is referred to as “This Lady (Miss Susanna Watts) ranks high in the present list of literary characters”.

She was also involved with a Leicester periodical, The Selector, which ran from 28 August 1783 to 29 January 1784. In 1804 she published A Walk through Leicester, which is amongst the earliest guidebooks ever written about a large industrial town in England.

The following years were not easy for her as her mother became mentally ill from around 1806. On 19 March 1807 Watts’s friend, Elizabeth Coltman, wrote to the publisher Richard Phillips on Watts’s behalf, urging intervention from the Literary Fund for one whose ‘character and talents’ would have been ‘among the most distinguished of her sex, had they been nurtured by genial circumstances’.

"Among her accomplishments, Coltman mentions Watts’s receipt of ‘a medal’ from the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts." (“Susanna Watts | British Travel Writing”) Manufactures, and Commerce for ‘some extremely fine landscapes entirely composed of feathers.’ The Literary Fund awarded Watts £20.

According to Shirley Aucott, a local historian and author, Susanna worked on a periodical called The Hummingbird, which brought together different ideas on the antislavery movement, and she organised what must have been one of the first fair trade campaigns. (“Leicester - Abolition - Susanna Watts - BBC”) She visited local households and shops to persuade them not to use sugar produced in the Caribbean, claiming that "abstinence from sugar would sign the death warrant of West Indian slavery."

In about 1828 Watts also founded the philanthropical organisation, The Society of the Relief of Indigent Old Age, where she was both Treasurer and Secretary, posts she held until 1840 as well as publishing books on the treatment of animals.

Her scrapbook, now held by the Leicestershire Records Office, is a large black ledger, heavily worn, of a type which might have been used by some hosiery manufacturer or Leicester shopkeeper but is bursting with letters, drawings, poems and ephemera: it is a record not of business transactions but of female connection, creativity and activism in Leicester in the early nineteenth century.

A Walk through Leicester

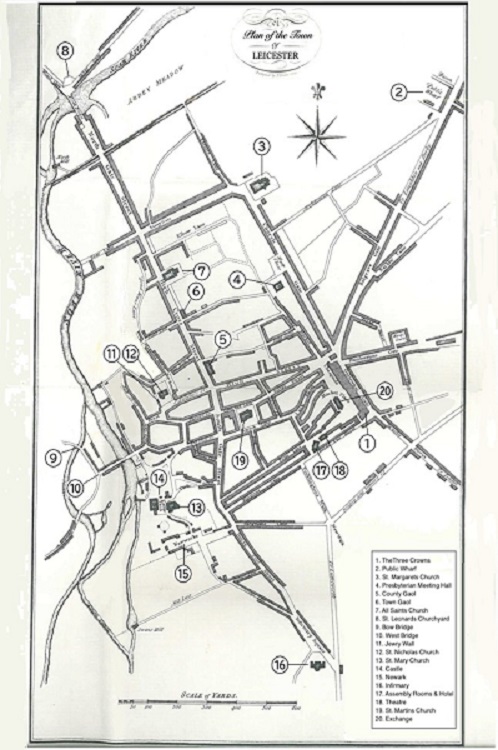

The above map shows the streets of Leicester as they would have been at the time Susanna published her walk. The numbers reference notable points of interest highlighted along the route.

A Walk Through Leicester invites the Visitor to begin a tour at the Three Crowns Inn (1) at the corner of Horsefair Street and Gallowtree Gate, a major Leicester coaching inn, built around 1720 and named in commemoration of the union of the crown of Hanover (George I) with England and Scotland in 1714. The inn was demolished in 1869 and a bank, the National Provincial and later a Nat West was located there.

Then up Gallowtree Gate to Humberstone Gate where Watts points out a range of new and handsome dwellings, called Spa Place (currently Allabout Pet Health), before moving to the Goltre Gate where several streets had recently been added to the town. She moves on to Belgrave Gate and comments at some length on the Roman milestone, milliare, which was found there in 1771, and then on further to the Public Wharf (2) and the canal where she recommends the view across the Abbey Meadow, extending on the opposite side of the canal.

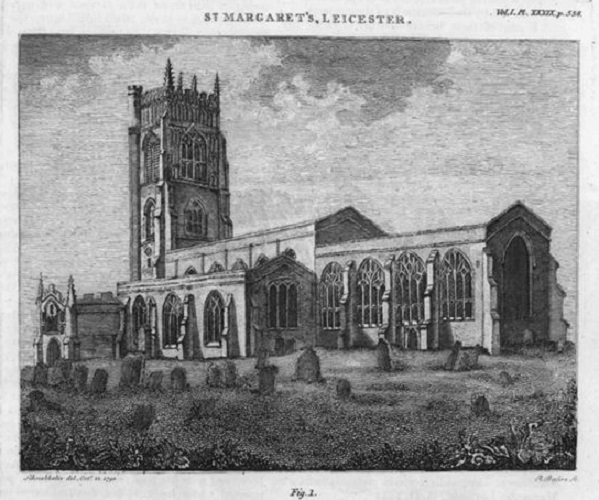

Passing back along Arch Deacon’s Lane, she arrives at and describes St. Margaret’s Church (3) and then points out Sanvey Gate to the west of the churchyard, the name apparently derived from sancta via, the route of the Whitsun Monday procession from St. Mary’s to St. Margaret’s.

The Visitor is then taken down Church Gate past Butt Close, named after the archery butts found there, and via an alley on the right past the Presbyterian (4) or Great Meeting House, built in 1708. Opposite was a new Meeting House for a society of Independents, and in the adjoining lane was another, built in 1803 by the Episcopalian Baptists. Between these last two buildings was an area known as the New Vauxhall which was used as a bowling green and tea garden, and in the same area was the lunatic asylum.

From there Watts took the Visitor past a street called the Swine Market, formerly Parchment Lane, and arrived at the site of the East Gates, demolished some years previously, and on to the High Street and High Cross Street where stood the County Gaol (5), built in 1791 on the site of the old gaol. Separated from the county gaol, by Free School Lane, was the Free Grammar School and on the opposite side of the street was the Blue Boar (afterwards the Blue Bell) inn, apparently where Richard III spent his last nights before Bosworth. At the bottom of Blue Boar Lane, which takes its name from the inn, was a small Alms-house, founded in 1712.

The next thing to be seen in High Cross Street, was the Town Goal (6), built in 1792 on the site of the remains of the chapel of St John. The small Hospital of St. John joined the prison with Bent’s Hospital on the ground floor, both hospitals being charities for the support of poor widows. The church of All Saints (7) was further up the street and beyond the church was the location of the North Gates. The Visitor could also pass along a narrow lane which formed the passage leading to a Meeting House, belonging to the Society of Quakers. The street moving onwards was then called North Gate Street and led to a bridge over the canal, beyond which was the North or St. Sunday’s Bridge. The churchyard of St. Leonard (8) was at the foot of the bridge in an area enclosed by a low wall, but no remains of the actual church remain there.

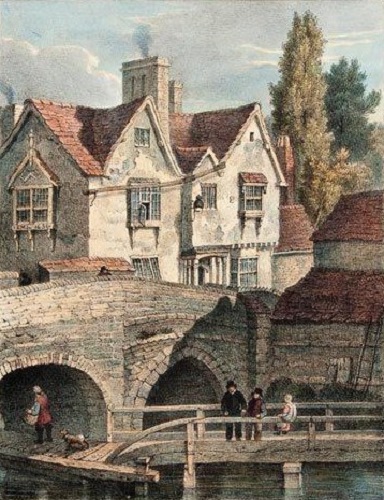

From the North Bridge two streets branched out, that on the left the Wood Gate leading to the Ashby-de-la-Zouch Road and on the right the Abbey Gate leading to the Abbey Meadow, the site of the Abbey. Watts recommends a walk through the Abbey Meadow to the navigation bridge at the bottom of North Gate Street and onwards to the Bow Bridge (9) taking in the views of the countryside and, in the distance, the village of Belgrave.

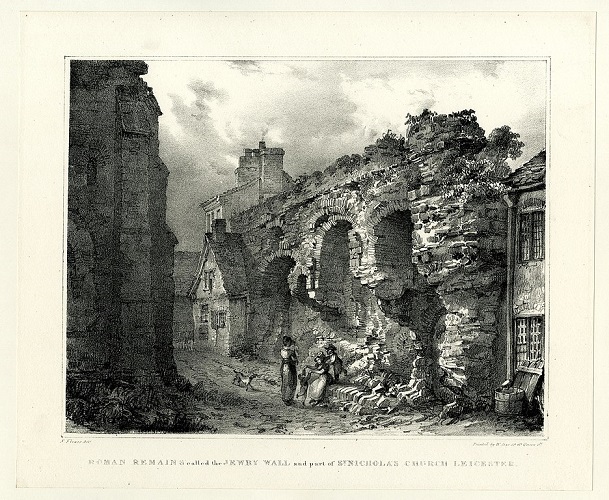

The tour then re-entered the town at the West bridge (10) and proceeded along Apple Gate to the church of St. Nicholas and the adjacent Jewry Wall (11). At the corner of this area was a charity school and, in a lane, not far from St. Nicholas’ church (12), called Harvey Lane, was the meeting house of the Calvinistic Baptists.

From St. Nicholas Street the Visitor arrived at the High Cross and proceeding southward along High Cross Street and turning down a narrow alley, called Castle Street, arrived at a spacious area on the right of which was a charity school, built in 1785, belonging to the parish of St. Mary. The Visitor would now have a full view of St. Mary’s church (13) near the north door of which was a passage leading under a gateway into an area called the castle yard and the site of the castle (14). Descending from the castle mount and passing through the south gateway of the castle yard, the Visitor entered a district of the town called the Newark (15).

From the Newark, in a lane opposite called Millstone Lane was a Meeting House of the Methodists, passing which the Visitor would proceed along South Gate or Horsepool Street to The Infirmary (16) and a quarter of a mile or so further on were some Roman remains, called the Raw Dikes, banks of earth four yards in height, running parallel to each other in nearly a right line for more than 600 yards.

From the Infirmary via the New Walk, three quarters of a mile long and twenty feet wide, made by public subscription in 1785, the Visitor could enter the town, or they could descend along the London Road onto Granby Street and turning to the left they could arrive at the town by the entrance into Hotel Street.

The Hotel (17) itself ‘from the grandeur of its windows, its statues, bassi relievi, and other decorations, can be justly considered as the first modern architectural ornament of the town’ befitting ‘polished society’ and, ‘appropriated to the use of the public balls.’

Adjoining the hotel was a small theatre (18) built by Mr. Johnson (the architect of The Hotel).

Passing through Friar Lane, the Visitor could observe a charity school, erected in 1791, belonging to the parish of St. Martin and at the end of this street was the Meeting House of the General Baptists. Passing down the New Street, part of the site of the monastery of the Grey Friars, the Visitor arrives at St. Martin’s Church (19) on the west side of which is a hospital founded about 1516, by W. Wigston, Merchant of the Staple at Calais, and Mayor of Leicester. On the north side of the hospital is a building called the Town Library, and next to that is the hall formerly belonging to the guild or fraternity of St. George, which was the Guildhall of the borough.

A short walk from St. Martin’s church to the Market Place brings the Visitor to the end of their tour in a spacious area surrounded by handsome and well-furnished shops and the Exchange (20), built in 1747 and the location of the local magistrates’ court.

Watts wrote A Walk Through Leicester in the period between the construction of the Grand Union Canal in the 1790s which linked Leicester to London and Birmingham, but before the opening of the first railway station in 1832. The text reflects the views and values of the particular class and culture to which she belonged and largely ignores the poorer or working-class areas of the town. Daniel Defoe in his A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain published between 1724 and 1726 describes Leicester as:

‘An ancient large and populous town ……. they have a considerable manufacture carry’d on here, and in several of the market towns round for weaving of stockings by frames.’

William Cobbett, who visited Leicester in 1830, described the town and its setting in very flattering terms. Another and perhaps more dispassionate observer, writing in the same year, remarked:

'While the town in less than thirty years has expanded to twice its former bulk, too little, it must be confessed, has been gained in elegance and beauty. The new streets have been laid out without much, if any, regard to taste and regularity, and the new buildings are in general destitute of ornament and uniformity.'

John Parker, of the Friends of the Centre for English Local History, Leicester, 2024.

Notes

The full text of A Walk Through Leicester is freely available as an e-book at Project Gutenberg or as an Apple e-book.

Also worth investigating is A Walk Through Leicester in the Age of Austen: An exercise in microhistory published as an abstract in the Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society Vol 95 (2021)

The author was prompted to take a look into the work of Susanna Watts by a presentation given by Colin Hyde given to the Friends of the Centre for English Local History in June 2024. Further details of which can be found here. The assistance of Gillian Rawlins in the preparation of this work is also very much appreciated.

High Cross Street and 'The Nag's Head', Leicester by John Fulleylove (1874) © Leicester Museums and Galleries Reproduced under Creative Commons Licence CC-BY-NC-SA. https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/high-cross-street-and-the-nags-head-leicester-81305/vie