Sunday 19 May 2024

A Ritual Landscape

LAHS Member Stuart Evans examines the evidence of a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age ritual landscape on the northeast boundary of Leicestershire with Lincolnshire.

This article covers the period from the middle of the 4th millennium BC to the middle of the 2nd millennium BC (3500BC to 1500BC); a time when the East Midlands was sparsely populated and occupied by small communities carrying out a form of subsistence agriculture. They used flint tools and although bronze was introduced in the middle of the third millennium BC, flint continued to be used extensively. They grew grain in small plots and wandered the landscape with their domestic animals returning to the plots periodically to sow, plough or harvest. This partially nomadic lifestyle has been termed "Tethered Mobility" (Cummings 2017).

Man is a social species and periodically these isolated communities would gather together in special places. We know at these gatherings they feasted and carried out rituals; probably exchanging items and ideas. They also built monuments - in the 4th millennium, they built causewayed enclosures and cursus monuments; this developed into the building of "henges" primarily in the 3rd millennium. The monuments took years to build and it is thought the construction was part of a ritual process. They buried some (but not all) of their dead ancestors in complex graves overlooking these sites, first in long barrows and later in round barrows. These wide open areas of gathering have been termed Ritual Landscapes (Robb 1998) and a very readable description of such landscapes has been written by Francis Pryor.

The most famous ritual landscape is the Stonehenge World Heritage Site. We all know the ring of stones but less obvious is the 25 km2 of the surrounding landscape. This is also part of the monument with the extensive features around Avebury and Durrington Walls, the cursus, circular structures, dozens of barrows both long and round and the ridgeway leading to it. There are many such gathering sites on these islands from The Ring of Brodgar on the Orkneys to Knowlton in Dorset - they are not always obvious because timber instead of stone was used in many structures and all that is left are the tell-tale cropmarks that are frequently difficult to classify (Gibson 2012).

A Sequence of Cropmarks

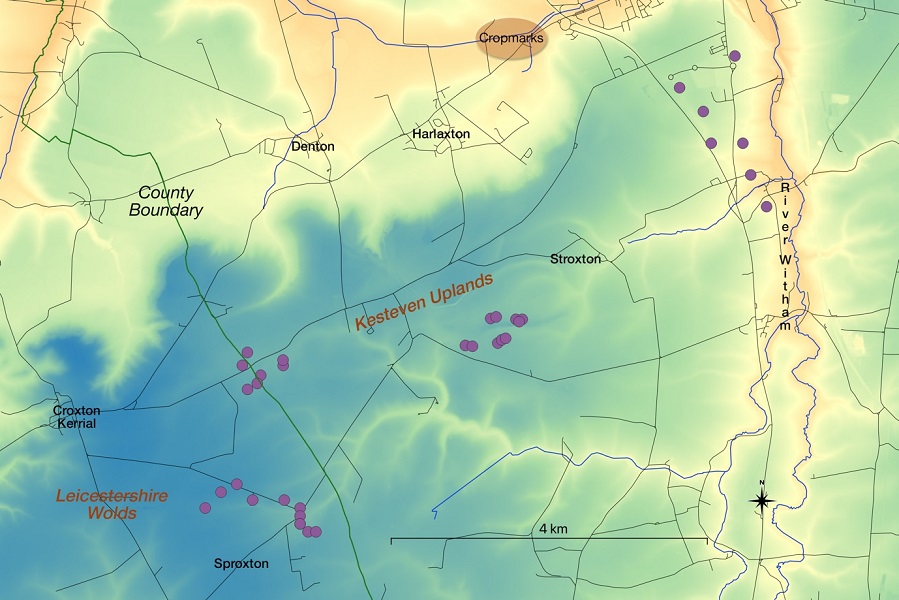

Some distinctive cropmarks have been recorded in the parish of Harlaxton, just over the Leicestershire County border with Lincolnshire, in a wide valley leading down to the river Witham at Grantham. (Figure 1)

This valley lies between the Casthorpe Hills to the North and a ridge to the south. This ridge runs from the Soar Valley where the hills are called the "Wolds" and into Lincolnshire where they are known locally as the "Kesteven Uplands". The valley runs to the northwest around the Casthorpe Hills into the Vale of Belvoir. The Nottingham to Grantham Canal runs through the valley.

These cropmarks are in four groups and have been interpreted by several authorities: -

- The main central area contains a semi-circle of large pits enclosed by a ditch, a segmented ditch circle and a group of four pits.

- To the west of the central area is a trapeziform long-barrow-type enclosure.

- To the northeast are four lines of pits, these linear features (considered a cursus monument) extend for approximately 250 m.

- To the northwest are two ring ditches.

These cropmarks have been subject to great scrutiny and described in detail by Harding and Lee (1987) in their comprehensive catalogue of "henges" in Britain. They have been photographed many times and some of the images can be seen online at Cambridge Air Photos. The National Mapping Programme has mapped these features and Heritage Lincolnshire has produced a video about the linear features (Heritage Lincolnshire 2021). This whole area has been interpreted as a ritual landscape and an important regional link (Jones 1998).

None of these cropmarks have been subject to magnetometry or excavation and the area is under cultivation (Figure 2)

The Surrounding Landscape

The wider landscape is also rich with features.

About 3 km to the west is a mound considered a degraded long barrow (MLI30017). Doubts have been raised about this classification but on closer examination with LIDAR, it does have barrow-like features (Figure 3) with a distinct ditch around it. One important aspect of this feature is that it overlooks the linear crop marks to the east (Figure 3 elevation profile).

There are other features in the wider landscape. On the ridge to the south of the valley, no less than 34 recorded round barrows/ring ditches1 run eastwards for 9 km along the ridge from Sproxton/Croxton Kerrial 2, to where the ridge drops to the Witham Valley (Figure 4). These are in 4 groups, 2 on the county border, a group at Stroxton and another group overlooking the Witham Valley.

The 10 barrows in the Stroxton area were all destroyed by quarrying in the 1950-60s but rescue excavation of 5 of these barrows found early bronze age burials with some interesting lithics (MLI34182).

The 7 barrows/ring ditches overlooking the Witham Valley are predominantly identified as cropmarks although one is still upstanding (MLI30082).

The two groups in Leicestershire were recorded in older texts and by modern aerial photography (MLE3567). One (MLE4091) was excavated in detail (Clay 1981) which revealed a complex turf, timber and stone structure with at least six cremation burials; one cremation was buried in a log coffin. Six samples from this excavation were dated using modern calibration (Brunning et al 2018) and all were shown to be between 2000 BC and 1500 BC.

Artefacts

Flint Scatters - There are a large number of flints recorded from around the area but most are random finds and not well documented. However, in 1968/69, the Archaeological Society of Kings School Grantham under the supervision of 2 archaeologists systematically field-walked most of Barrowby parish to the north of the cropmarks. They found Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age flints, including 5 Neolithic leaf arrowheads. The scatters were concentrated on the ridge of the Casthorpe Hills, overlooking the Vale of Belvoir with another concentration of Bronze Age flints leading towards the linear crop marks (Figure 1 and MLI30119, MLI30137). The diversity of these scatters indicates that there was a degree of continuity of human activity.

Pottery - In general Neolithic pottery is fragile and usually only found with cautious excavation. However, with the appearance of the Beaker people in the early Bronze Age a more robust pottery was produced. No less than 5 complete Beaker pots and 2 fragmented pots have been found between Belvoir and Grantham. These were primarily discovered in the early part of the 20th century by ground workers digging iron ore or sand. The contexts of the finds were not well recorded but the majority are thought to be cremation burials. Most of these Beakers are in museum collections although 2 are in private hands. Figure 5 shows the Denton Handled Beaker and a further 2 can be seen online at the Ashmolean Museum and the British Museum.

In addition, two Early Bronze Age Collared cremation urns were found at Harston (MLE6367) and the predominant pottery sherds in the excavated barrows were from Collared urns although Beaker fragments were also present.

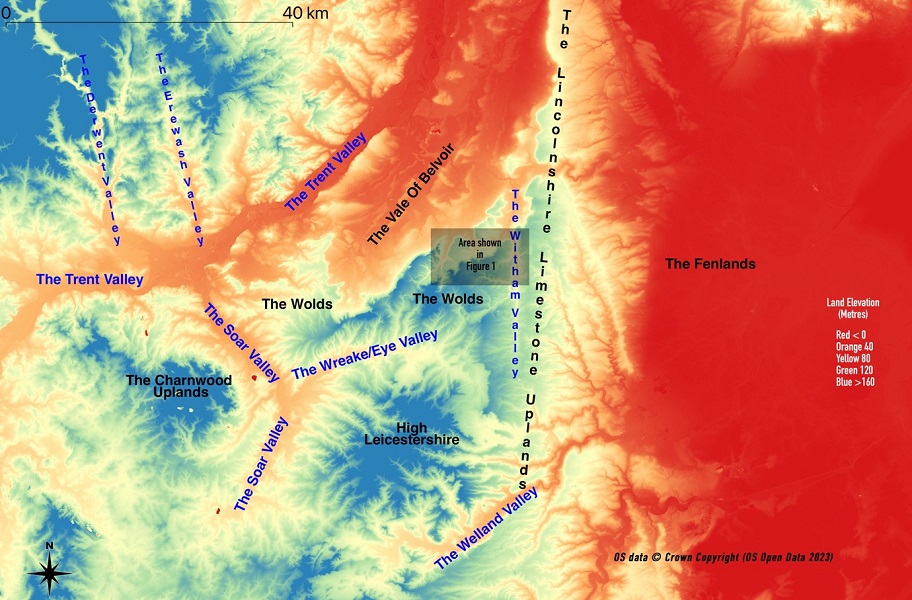

Location - Why gather at Harlaxton?

In 1977, James Pickering, a pilot, aerial photographer and amateur archaeologist, described "The Jurassic Spine". This is a limestone ridge that runs from the Humber, south along the Lincolnshire Uplands to Stamford (Figure 6), it then continues southwest to Banbury. This was interpreted as an ancient trackway and runs less than 3 km to the East of the main features; a good North/South link. In addition, the Leicestershire Wolds run across North Leicestershire into Lincolnshire a kilometre to the south of Harlaxton; an East/West link. Does this ritual landscape lie at the junction of 2 ancient trackways? The origins of trackways are controversial (Bell 2020) but it is thought the Neolithic people used the higher firmer land to move significant distances.

The communities would have travelled here probably from the Soar and Wreake valleys across the Wolds or the hills of High Leicestershire. Communities from north Lincolnshire would use the limestone uplands and the fen edge communities would have also used this track. All of these dispersed areas have significant numbers of records confirming Neolithic and Early Bronze Age / Beaker activity.

Discussion

Individually most of these observations have a degree of uncertainty - cropmarks are not definitive, the long barrows are far from proven, the artefacts only indicate periodic occupation and the trackways are speculative, but viewed collectively the uncertainty reduces significantly. Of course, these features developed over 1500 years and may have been used intermittently at different times but the correlation with other ritual landscapes is noteworthy.

This landscape includes a potential cursus, which leads to an area with circular earthworks and long barrows in the vicinity. The landscape also has an extensive spread of round barrows on the hills to the south, similar to Stonehenge (Banton 2016) and other sites.

The Beaker's presence is also interesting - these European migrants appeared in our landscape between 2400 and 2200 BC. Bradley (2019) links the Beaker's arrival with the escalation in monument construction and observes that Beaker burials, although present at many sites, were usually a short distance away. For example, the Beaker burials excavated at Amesbury were 5 km from Stonehenge. There is an extensive Beaker presence a short distance from the main features at the Harlaxton site stretching from Grantham well into Leicestershire around Belvoir.

One can only speculate on the movement of various communities in this period of prehistory. There are other ritual sites in the East Midlands Region. The most significant is 40 km south at Maxey and Etton in the Welland Valley described in an earlier reference (Pryor). There is also a causewayed enclosure to the south of Leicester at Husbands Bosworth (MLE8358) and several features in the Trent Valley between Holme Pierrepont and Newark and at the confluences of the Derwent and Erewash with the Trent.

By the early part of the 2nd millennium BC, the construction of large ritual monuments had declined and more local ceremonial enclosures started to appear. The population was growing, and the tethered mobility was declining. The social and economic needs of the communities could be met without travelling to gatherings at the large ritual sites. The land started to become enclosed - it was becoming a commodity. The ritual landscape was probably still revered as the land of their ancestors; however, the communities did not gather to construct and maintain the landscape as they had done in the previous two millennia.

Footnotes

- Round Barrows are usually detected as round crop marks and are more correctly termed Ring Ditches.

- The barrows at Croxton Kerrial are at the parish boundary with Sproxton, older texts record this as Saltby, the name before 20th-century parish reorganisation.

References and Supporting Information

Text underlined and in bold type is hyperlinked directly to the reference or web-based information.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to the various county Historic Environment Officers who maintain the HER database and have patiently answered my many queries.

Copyright

LIDAR Data was downloaded from the DEFRA survey and is subject to the Open Government Licence v3.

Correspondence

stuartevans4@icloud.com

The recorded features in the landscape between Knipton and Grantham. Contains OS Open Data © Crown Copyright (database right) 2023, licenced under Open Government Licence 3.0. Annotated by Stuart Evans