Sunday 5 May 2024

A Picture Postcard Puzzle: The burial and re-burial of Friar John

LAHS Member Nick Miller recounts the intriguing story of a medieval burial, re-discovered in Edwardian times on the site of an old friary, culminating in a funeral to remember for a local town.

The picture

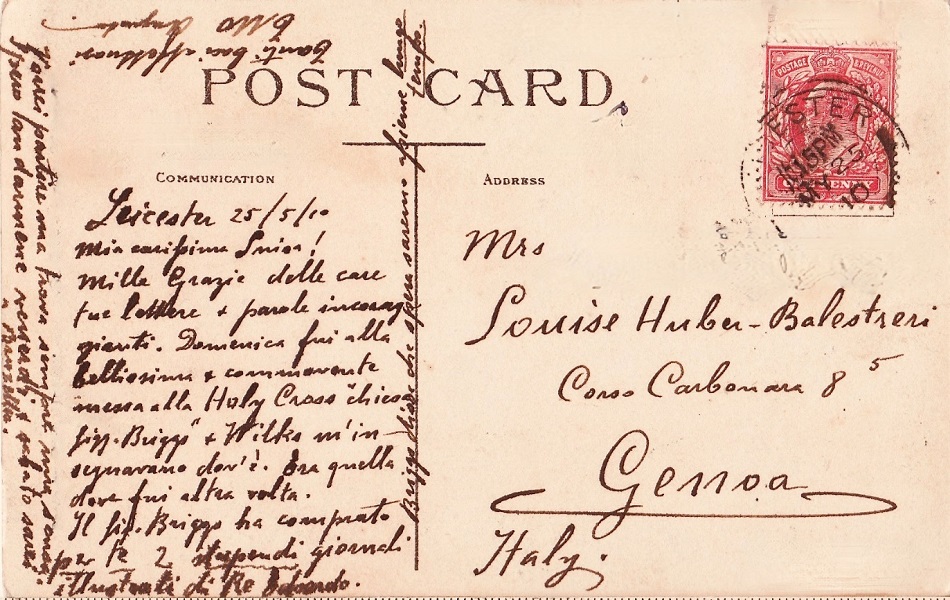

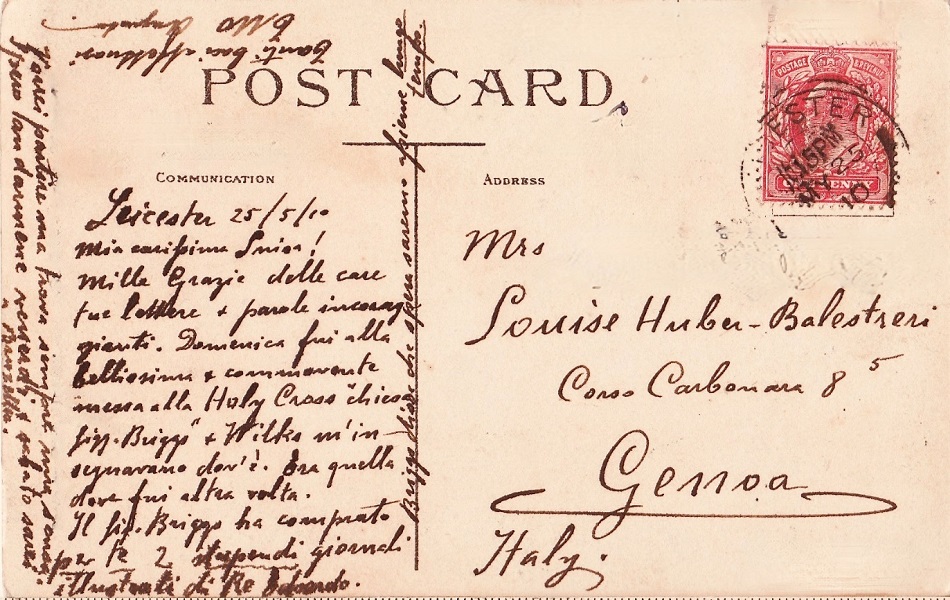

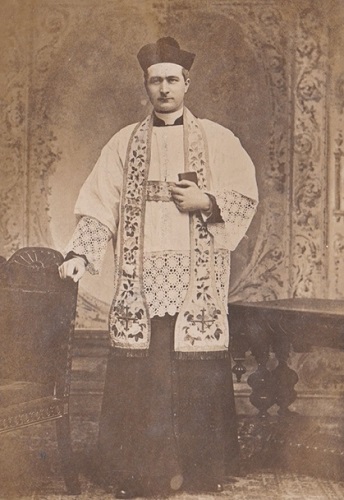

A postcard of priests officiating at a reburial. That’s Father Caus of St Peter’s (King Richard’s Rd) Leicester first from right. The card is posted from Leicester to Genoa in May 1910. Augusto, over on boot and shoe business it seems[1], writes in Italian, of enjoying a most beautiful mass at Holy Cross priory on New Walk in Leicester. Except the image is not Holy Cross, nor immediately recognisable as any Leicester(shire) location. And who was Friar John? And why did he need to be reinterred?

The following relates the story behind the postcard. The tale, though, leaves many questions unresolved. The blog speculates on some of the possible answers. Warning! Archaeologists of a nervous disposition may find parts of this account distressing.

A 9.9.9. call

Person searches revealed no record of John at Holy Cross in Leicester, nor around Leicester(shire) generally. Enquiries at the Dominican archive in Oxford (Holy Cross is a Dominican institution) drew blanks. Digging in Catholic newspapers contemporary with the postcard turned up trumps.

A piece in the Nottingham and Midland Catholic Herald[ii]established that the location of the action was in fact Stamford (Lincolnshire). Further searching disclosed other, occasionally conflicting, press reports from Stamford[iii] and Rutland[iv]. They revealed that on Thursday 9 September 1909 workmen from Woolston’s building company[v]undertaking drainage work behind 7 Adelaide St in Stamford unearthed a lead body-shaped object. Mr Sharp, the foreman, promptly notified his boss, and Corby and Son, the architects of the work. John Woolston, Joseph Corby and George Burton, sub-editor of the Stamford Mercury, were soon on the scene.

Around the object were traces of wood and rusty nails, suggesting it had been in a coffin. From its depth (168 cm/5’6”) and east-west orientation onlookers assumed a Christian burial. The association of the Adelaide St cottages with the site of the former Blackfriars’ (Dominican) priory reinforced the supposition. The exact disposition of buildings within the priory is unknown, so it’s unclear whether the burial was in- or outside the main church, and if inside whereabouts. It was not the first body (nor the last) yielded up by the cottages and their gardens[vi].

The workman’s pickaxe had pierced the lead at the head end. An unbearable stench from the find deterred them from inspecting it in situ, so on Friday evening they removed the bundle to Gibson and Sons ‘yard. The Gibsons, local mechanical engineers, owned Adelaide cottages.

It seems the intention was to scrutinise the find and afterwards reinter the remains. Present at this inspection were Mr Woolston, Mr Corby, Robert Gibson, Dr Hall representing the Medical Officer of Health, the borough surveyor and inspector of nuisances Frederick Ryman, members of the press and a policeman.

The workmen cut along the length of the lead and prised it open. As anticipated, they found a body wrapped in cerecloth (a later inspection - below –counted six layers), further secured with waxed cords and additional cotton banding around the loins. Attracting attention was a bulge on the chest. When exposed they found one hand (reports differ on which) across the breast, the other by the side.

There was also an object measuring around 9x5cm (3.5”x2”). When this was uncovered and unfolded it turned out to be a document written in Latin on sheepskin, ca 25.5x40.6cm (10”x16”). The parchment and text were darkened and indistinct, so it was washed in water, of course immediately degrading any text still legible. The seal was similarly soiled so was scoured with a wire brush, likewise, rendering recognition impossible.

Just discernible were the letters ‘Ioan’. Based on this, the apparently prestige status of the burial, plus the fine hands seen when the bulge was uncovered, the local rumour mill buzzed into action. These must be the remains of Ioan/Joan (1328-85), the Fair Maid of Kent, wife of the Black Prince, first princess of Wales and mother of Richard II[vii]. Her will of 1385 expressed the wish to rest beside her first husband in the Franciscan, Greyfriars ‘church in Stamford, believed to have stood close to Blackfriars. People presumed her coffin ended up at Blackfriars because it was transferred there when Greyfriars was dissolved (1538) –ignoring the fact that Blackfriars was dissolved then too.

After inspection, the corpse was buried with quicklime shovelled over it ‘in an obscure grave’, close to some manure heaps in one of Woolston’s fields. The lead, it seems, was saved for selling. That was not the end, though. Certain parties considered higher authorities ought to be consulted.

A difficult read

A photograph of the document was conveyed to George Warner at the Manuscripts Department of the British Museum. They subsequently requested inspection of the original.

Following painstaking work their verdict was that it was an indulgence (the terminology is mistaken – see below – it was an indult) granted by the Pope to Iohanni (so not Joan) Staunford, ‘clerico Lincolniensis’–or possibly ‘canonico’, given the defaced lettering. The brief empowered Staunford’s confessor, ‘whomsoever he may choose for that purpose and whensoever he makes confession, to grant him full remission of all his sins’[viii]. Why he might want or need permission to err from the prescribed norms in church law concerning choice of confessor is pondered below.

Handwriting comparisons to contemporary documents of known provenance verified the authenticity. The wording reflected the standard formulaic language for such permissions. Cross referencing to papal registers[ix] confirmed an indult was granted to a John Stawnford on 28 March 1398 by Rome’s Pope Boniface IX (1389-1404).

This again scotched speculation the text referred to Joan. She died in 1385.Nevertheless, to add certainty Warner advised inspection of the corpse by a qualified practitioner, and to notify Herbert Gladstone, then home secretary, whom he had advised of the situation.

The examination fell to George Boyd, surgeon at Stamford Infirmary. Present also were Father Joseph West, local Catholic priest, Herbert Traylen, Lincoln diocesan surveyor of ecclesiastical dilapidations, and other town worthies. The body was remarkably preserved. The figure was definitely male, age early seventies, with a beard and a clearly defined tonsure. With these ends tied up the next stage in the story commenced.

A funeral

Gladstone instructed the town authorities to rebury the body with fitting respect in consecrated ground, intimating that since the body hailed from pre-Reformation times (re)burial should follow Roman Catholic rite. Discounting some Anglican voices to the contrary (below), the Marquess of Exeter[x], and Charles Atter, town clerk, invited Father West to arrange the proceedings.

The re-encased body was placed into a fine oak coffin. The indult parchment was kept, but a glass phial containing a note in Latin of the happenings and findings of the last weeks was enclosed. On 6 October, the coffin was brought for the wake to St Mary’s/Our Lady and St Augustine, where it lay in the sanctuary overnight illuminated by candelabras and tapers.

Next day Our Lady’s was overflowing for a full requiem mass. Accompanying Father West were Father William Lieber from Sleaford and Father Francis Caus from St Peter’s in Leicester[xi]. Chief celebrant was Fr John Placid Conway OP, STM, with Fr Norbert Wylie OP acting as deacon and Fr Theodore Bull OP as subdeacon.[xii]. These three were invited from Holy Cross Dominican priory in Leicester given Fr John was most probably a Dominican.

After the mass Father West held a short address before the prayers and chants of commendation and absolution, following which the body left to the strains of the Dead March from Händel’s Saul, played on the organ by Miss Wells. The procession wound through the town, the coffin on a hearse, headed by a cross-bearer, acolytes, a thurifer and holy water bearer, clergy and choir, a public spectacle not witnessed in Stamford for nearly 400 years.

Committal took place in the catholic plot at the town cemetery. A marble cross marked the grave, still there today, in honour of ‘Friar John twice buried 1400 and 1909 RIP’.

A spat

Notwithstanding Gladstone’s and the corporation’s opinion that ceremonies should follow Roman rite a mini-interdenominational spat arose, with some Anglican clergy arguing precedence.

At stake was whether the church in England’s split with Rome at the Reformation had disqualified it from continuity with the pre-Reformation church. James Camm[xiii]rector of St George’s was one who argued Staunford was a member of the Anglican communion, appealing to King John’s Magna Carta that England shall be free and Richard II’s 1393 Great Statute of Praemunire forbidding appeals to the papal court. Father West based his address on I Samuel 12:23[xiv], ‘…far be it from me that I should sin against the Lord by ceasing to pray for you …’, underscoring pre-Reformation doctrine and belief still held by the Catholic church that prayers are needed in perpetuity to ease the soul’s journey through purgatory and on to Heaven. The Nottingham Dominican journalist smugly concluded, ‘The moral of the ceremony was obvious to the people of Stamford, that the Anglican clergy have no continuity with the bygone clergy of England in her Catholic days’.

All dead and buried?

So, Friar John received his reburial, and that might satisfy some enquiring minds wanting to solve the postcard mystery. But other questions remain unanswered that surely leave other minds unsettled.

He was a cleric. But was he a friar, a prior even? At Blackfriars? A priest from somewhere else in the Lincoln diocese? If the latter, how come he was interred at Blackfriars? More pertinently, why did he want or need an indult, and why did this have to come from the Pope himself?

An indult grants the holder leave to override some aspect of law. Depending on the seriousness of the exception the issuing authority may be the Holy See or a bishop acting within powers assigned him. John’s indult gave him the right to choose his own confessor rather than the one assigned to him by dint of his role, rank, regulations of his order and the nature of sins to be confessed.

Maybe he just wanted the indult as an added insurance policy should he ever need it. Perhaps he fancied himself above convention with respect to confessions. It’s unlikely an indult would be issued on such whims, especially from the Pope. The temptation is to believe that some spiritual or worldly impediment in his circumstances would make his allotted confessor reluctant to absolve him. One can only speculate, but there is no shortage of possibilities.

Was there a royal intrigue? Stamford and the Blackfriars’ priory regularly entertained nobility and royalty. Were there irregularities in his accession to the priesthood and/or promotion during the confusion and corruption following the Great Pestilence?[xv].Was he entangled in Lollard activities, rife across nearby Leicestershire? Ralph of Spalding at neighbouring Whitefriars’ was a Wycliff sympathiser. Did he rouse disfavour around poll tax protests or the Peasants’ Revolt? The family of battling bishop Henry le Despenser of Norwich had a chapel in the Blackfriars’ priory. Despenser set forth from there to quash disturbances in Peterborough and East Anglia[xvi].

Were matters more local? Disobedience and insubordination towards superiors happened. Had he squabbled with colleagues who might have been his confessor and appealed over the head of his superior to the pope? In 1373 the Stamford Blackfriars had writs issued against them because friars had entered into contracts without knowledge and permission of the prior and received loans which had not been used for the benefit of the priory[xvii]. Monks regularly meddled in worldly disputes. Robbery, death, and injury were not uncommon. Goings-on at nearby Sempringham and Haverholme priories during John’s lifetime serve as apt illustrations[xviii].

Was John maybe associated with fellow Blackfriar Henry Aldwinkle. He was imprisoned for a carnal sin, escaped, appealed to Rome without permission from his superiors but, eventually, by the 1390s, was restored to grace in questionable circumstances, with other friars forbidden to allude to his past.

Are any of these possibilities near the mark, or still way-off? Or do we do him a great disservice, there was nothing untoward? Alas until documents yet to be discovered shine light on his role(s) and demeanour inside and outside the church we can only guess.

Nick Miller has an interest in ecclesiastical history. He is author of Church History in Leicestershire, Book Guild, Market Harborough, 2024

Endnotes

[i]The message notes meetings with Mr Briggs and Mr Wilks. Inspection of Kelly’s and Wright’s directories for Leicester in 1908 and 1909 suggests they were: Francis and/or Thomas Briggs of TN & FH Briggs Co, boot and shoe manufacturers (one of their premises was on Wellington St near Holy Cross). They also owned a leather works on Waring St. John and/or Arthur Wilkes of Wilkes Bros, and/or of Tilley, Akins and Wilkes, were also boot and shoe manufacturers.

[ii]Nottingham and Midland Catholic Herald, 16 October 1909, page 4. Articles by ‘A Dominican’ and Rector, Father West

[iii]Lincoln, Rutland and Stamford Mercury, 17 September 1909, page 4; Lincoln, Rutland and Stamford Mercury, 8 October 1909, page 4

[iv]The Rutland Magazine and County Historical Record, vol 5, 39, pp219-224, 1912. This is an amalgam of the previous reports, but adds the correspondence with Warner at the British Museum

[v] Woolston was also deputy mayor at the time.

[vi]There were human finds in 1840, 1887, 2018. See Lincolnshire County Council, Lincolnshire Heritage Explorer, 2018: Unpublished Document, SLI17295 - Human Remains Found at 4 Adelaide Street, Stamford (August 2018)

[vii]The Rutland Magazine report, p220, wrongly states Richard III.

[viii]Letter from Warner to Herbert Traylen, Lincoln diocesan surveyor of ecclesiastical dilapidations, 24 September 1909. Herbert was the son of John Traylen, architect, who designed St Paul’s and St Leonard’s churches and several other buildings in Leicester and was one-time surveyor to the Archdeaconry of Oakham and of Lincoln. Father and son had an architect practice on Broad St in Stamford.

[ix], Calendar of Papal Registers. See Bliss and Twemlow Papal Letters, vol. V, p112. 5 Kal April (=28 March). He is spelled Stawnford there.

[x]As lord of the manor and chief landowner

[xi] St Peters Leicester was founded ultimately by Dominicans from Holy Cross

[xii]The Stamford Mercury and Rutland Magazine state that the celebrant was the famous Dominican scholar Vincent McNabb, at that time attached to Holy Cross. One is hard pushed to definitively identify him as one of the celebrants on the postcard.

[xiii] Letter from Camm to Charles Atter, town clerk, 1 October 1909

[xiv]Wrongly recorded in the Nottingham piece as 1 Kings 7

[xv]Archbishop Sudbury (brutally beheaded 1381) branded sections of the clergy as ‘so tainted with the vice of cupidity that they are not content with reasonable stipends, but demand and receive excessive wages. These greedy and fastidious priests vomit from the excess of their salaries, they run wild and wallow, and some of them, after sating the gluttony of their bellies,

break forth into a pit of evils’, see N Miller 2024 Church History in Leicestershirep176

[xvi]A flavour of Despenser’s rampage in Peterborough comes from Henry Knighton of Leicester abbey in his Chronicle (June 1381): ‘Some were struck down with swords and spears near the altar and others at the church walls, both inside and outside the building … the bishop gladly stretched his avenging hand over them and did not scruple to give them final absolution for their sins with his sword…’

[xvii]See for instance 'Friaries: Stamford', in A History of the County of Lincoln: Volume 2, (London, 1906) pp225-230. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac... [accessed 17 April 2024]

[xviii]See for instance, 'Houses of the Gilbertine order: The priory of Sempringham', in A History of the County of Lincoln: Volume 2, (London, 1906) pp179-187. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac... [accessed 17 April 2024]

Background image: Augusto’s postcard message (1910). Provided by Nick Miller

Augusto’s postcard message (1910). Provided by Nick Miller