Sunday 21 April 2024

675 years ago, this weekend: a field headland at the Kilby parish boundary

LAHS Treasurer Simon Atkins assesses what features in the landscape can tell us about the past, through an analysis of maps and LIDAR images, combined with what is still visible today.

If the weather’s good in the next few days, I’d like to take you to a spot where you can travel back in time. It’s easy to get to; barely ten miles from the middle of Leicester. You won’t need any special equipment; decent shoes might not be a bad idea, and perhaps a map, although everything you need is on a phone, these days.

Before I take you to the spot, a bit of background. Over the last couple of years I’ve started to develop something of an obsession with parish boundaries and what they can tell us about the landscape when they were set out. I’m particularly interested in questions of human geography - why this boundary is here, not there.

Parish boundaries – whether rooted in Saxon boundaries, Roman estate boundaries, Iron Age or Bronze Age boundaries – often follow natural features in the landscape, as you’d expect; the boundaries needed to move along, and between significant and memorable places in a world without maps. Many boundaries follow streams; tops of hills were useful too; four parishes meet at the top of the Langton Caudle ridge, for example. Interestingly, there are often small ‘kinks’, very brief diversions in the general direction of the parish boundary where they cross known Roman roads. I think that’s evidence that the Roman road was extant in the landscape when the parish boundaries were formalised; the road, like a hill or a stream or a large stone was a significant ‘hook’ in the landscape, a memorable point on the path of a boundary.

Someone, sometime laid out the parish boundary; they made choices based on what they saw. Where we now see anomalies in the track of a boundary, they saw something of significance in the landscape and incorporated it into their route, taking a few steps to the left or right, marking a place, to make it memorable for the benefit of those repeated visits ‘beating of the bounds’ across countless generations. Each anomaly today was a place of significance in the past. I’m interested in finding these points in our present, and attempting to identify why they were significant within the landscape in the past.

I came across this particular anomaly in a parish boundary entirely by chance. I was walking from Arnesby, via Arnesby Lodge Farm, north towards Wistow one afternoon in the summer of 2022.

Kilby Grange Farm – 1:25,000 scale map

This is my favourite type of map for walking - I’m a big fan of the Ordnance Survey’s “Explorer” series at a scale of 1:25,000, because it has field boundaries, so you’d struggle to get lost.

North is at the top of the map. I crossed the Fleckney Road and walked north along the bridleway (the long green dashed line) into a field, with the hedge line (the thin black line) on my right.

I crossed a stile. Kilby Grange Farm was ahead of me to my left, and as I walked along the bridleway up a gentle slope I spotted, directly ahead of me on the skyline, a series of lumps and bumps stretched out on an east-west axis on the 110m contour.

As I reached the feature the farm was to my left. Immediately to my right, the field boundary had an interesting 'kink' - on the same 110m contour line – and the hedge line coincided with the parish boundary (the long grey dashed line.)

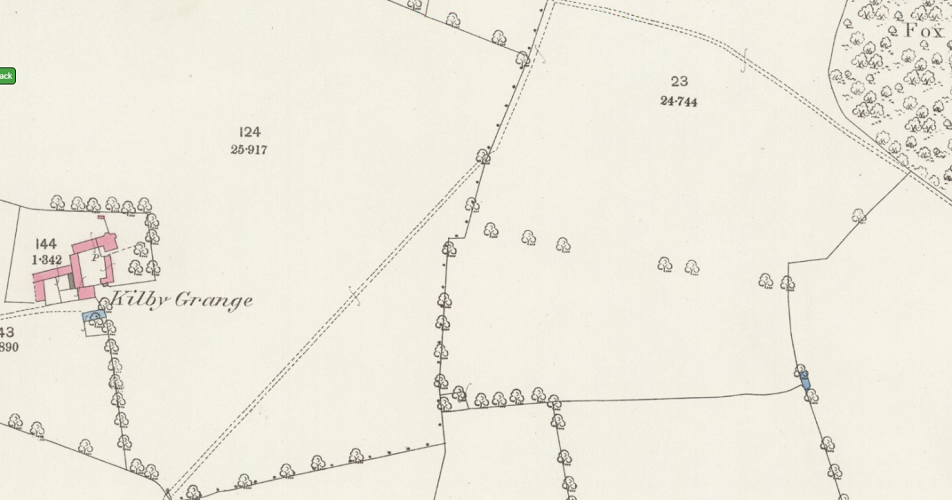

Kilby Grange Farm – 25 inchscale map (1885)

The ‘kink’ is clear on the 1:25,000 map, and it’s much more obvious on the old six- and twenty-five-inch maps (the single dots are the parish boundary; Kilby to the west, Wistow to the east.) There’s also an old tree line recorded, presumably the line of an old hedgerow, in the next field to the west, ending at the kink in our field.

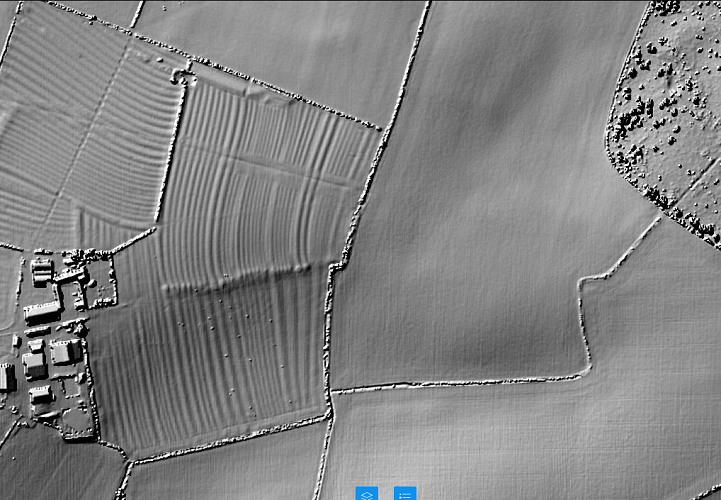

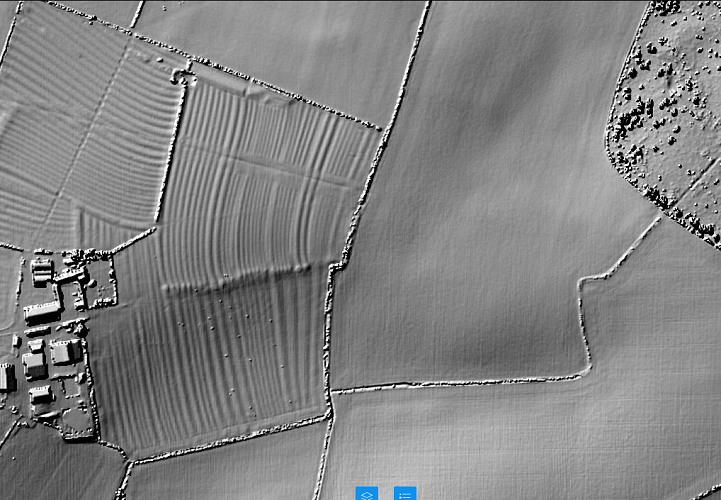

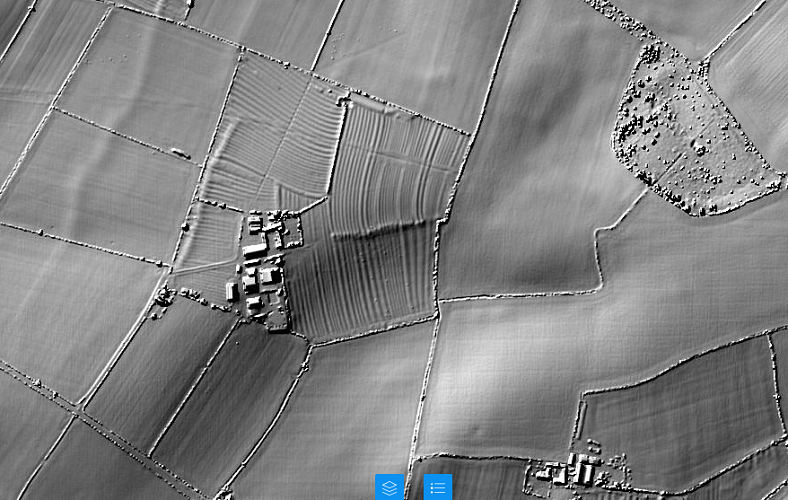

LIDAR Image

95% of England has now been mapped by LIDAR. If you’ve not come across it before, it works on the same principle as radar, but using laser light instead of radio waves. Because laser light has a much shorter wavelength, it can resolve much smaller features. In the image above, you can clearly see field boundaries, ditches, buildings and, in the left-hand part of the image, medieval ridge and furrow plough scars. Modern deep ploughing has ‘smoothed out’ field surfaces in the right-hand part of the image.

Looking at the LIDAR image, there definitely seems to be some sort of linear feature between the modern farm and the ‘kink’ in the parish boundary.

The feature – which looks like a raised linear earthwork –must logically be older than the medieval ridge and furrow, which runs straight over the top of it.

Pulling back on the LIDAR image, the feature is also in line with the farm access road.

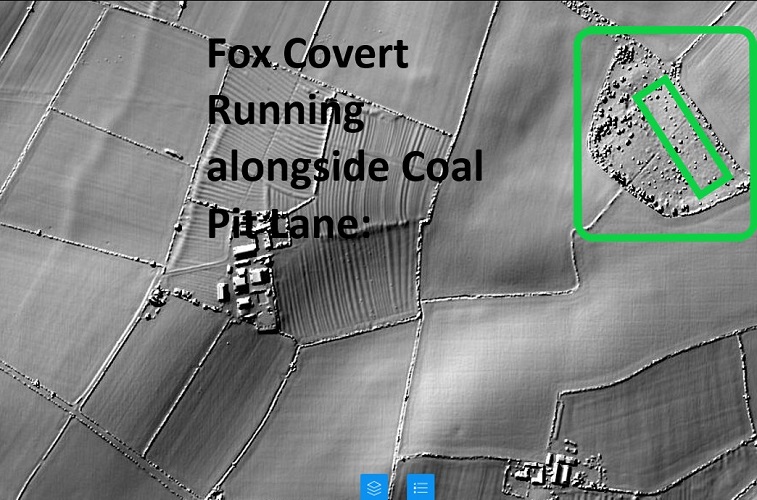

The eagle-eyed reader will be drawn to the fox covert in the top right of the image. Within the ‘pudding bowl’ shape of the covert, there’s a distinct rectangular depression on a north-west to south-east axis, which may be 250m x 100m. You can get into the fox covert quite easily in the south-east corner and have a walk around; it’s scrub, rather than thickly wooded. The feature isn’t obvious on the ground; if anyone’s got any bright ideas what it is, do drop me a line, and I’ll raise it with the Oadby & Wigston Field Walk Group.

How to travel in time

Go and stand with your back to the ‘kink’ in the hedge line, and look towards the farm.

You might notice the smell, first. Grassy breath. That’s the team of eight oxen, pulled up hard by your right hand; you could reach out and touch the leading beast. They’re big, but docile. They’ve barely stopped, and they’re calmly chewing the cud already. Nothing to worry about. Voices next; half a dozen men from Kilby. They’re standing on our earthwork feature; you suddenly notice it’s not a broken path of lumps and bumps any more, but a low, flat, grassy bank running away from us towards the west. As we look along the bank, it’s clear what it is, now – it’s a field headland, a track across the field that’s also a space to turn the long, unwieldy, slow team of oxen around,and set them back across the gleaned field to your right.

The voices are clearer, now; low, sombre, determined, serious. It’s a big thing they’re about to do, a big change for the village, the biggest change for generations.Relief, perhaps in the voices too; this will transform the village, which has been constrained, compressed, suffering from too many new mouths and too little to eat, especially in the bad times, and there’ve been enough of those in the last few years. Glances are exchanged. A nod of the head, the ploughman flicks his goad, the team move; not a turn sideways and back, but a pull forwards, straight across the field headland, the pitted and patched wood of the share pulling through the turf, down the gentle slope to the south. The men move away. There’s wetter ground downslope, but needs must. More land needs to be brought into productive use; the population is going up, and the peas and wheat must be grown somewhere. It’s a shame to move on past the kink in the hedge that marked the old edge of the field for the men and their fathers long gone, but that’s progress.

You glance at your chronometer – the one you downloaded with this article. It shows exactly 675 years ago, to the minute and day. If you linger a few more hours, you’ll see the ploughman and his team struggle to pass back and forth across the field headland, and start to break it up a little. At dusk they go back to the church in Kilby. The plough is locked away in the nave, the oxen tethered outside the churchyard, and you’re back home, too. You might wonder why the headland survived, but that’s simple; the great pestilence arrived a couple of weeks later. That’s the reason the headland was never fully ploughed out – the ploughman never came back to finish the job, and the pressure to bring land into cultivation from the waste disappeared, too. It’s the Spring of 1349; and not five miles away in the manor of Kibworth Beachamp, the first deaths were to be recorded on the 29th of April. The kink in the boundary, the field headland scarred by a single pass of a wooden plough; it’s a moment frozen in time, there for all to see.

The anomaly in the present and the significance in the past: what’s happening here?

The kink in the parish boundary was at the edge of the cultivated fields; that’s what made it significant in the landscape in the past. When the parish boundary was formalised and laid out, the edge of the ploughed land, plus the field headland, was an obvious feature in the landscape, and was 'marked' by a small digression from the general route of boundary line. (Analogous to the ‘kinks' in the path of a boundary crossing an extant roman road; that would also have been a memorable and useful 'hook' in the landscape.)

We know there was a field headland there, because we can still make it out on the LIDAR image.

During the first half of the fourteenth century the population of England grew to perhaps 6 million. The climate was probably balmier and cropping was easier than it had been for decades. However, farming was inefficient. In good years there would be a decent surplus, in poor years, famine. As the population grew, there was a shortage of cultivated land.

The significant thing is the partial destruction of the field headland. My thesis is that partial destruction occurred in the spring of 1349. The decision had been made at that date to expand the area of cultivation. In my imagined scene, that's what's happening.

Prior to that day, the field to the north part of the ridge and furrow we can see had been long cultivated. After that day, the south part of the field - formerly waste land - was ploughed for the first time (that's 'waste' in the sense of unploughed; it will certainly have been used for grazing)

I'm arguing it happened in spring 1349 because the field headland was partially, not completely, destroyed by overploughing. We can see from the lidar image that the plough scars run straight over the top of the field headland and have partly, but not completely, removed it. If the decision to extend cultivation had been made in (say )1329 there'd be no headland to see in the modern image; the headland would have been completely rubbed out, with even a few years of medieval ploughing. It wasn't totally destroyed because the plough team never came back to finish the job.

It's estimated that 50% of the population died during the Black Death. Suddenly, there was more than enough land to feed the survivors; and the survivors retrenched onto the 'core' cultivated lands of the village.

One of the significant impacts of the Black Death on the Leicestershire landscape was retrenchment and abandonment of villages on higher or more marginal land - there are a lot of deserted medieval villages dotted round east Leicestershire in particular, and they started to decline after the Black Death. It's unlikely that everyone in the more marginal villages simply upped sticks and left that year, but it's plausible to think that they drifted away over the next few years; there would have been vacant land in better sited villages, and a lord in the next valley may well have been offering better terms for a lease (with a lower rent and less labour obligations, perhaps.)

Thanks

I owe a big debt to John Lacey, who I first met at ROLLR in November 2021. He was looking at the plans for the Abbey Road Pumping Station and I was looking at Enclosure Maps of Glooston and Slawston for traces of the Gartree Road. He highlighted a 'kink' in the parish boundary at Port Hill (GR 787933), and that’s what set me off looking for, and at, these anomalies in the first place. I’d spotted this Kilby-Wistow earthwork and ‘kink’, but it was John who identified it as a field headland.

Notes

This field is about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north-west from the middle of Fleckney. The map I used is OS Map 233 “Leicester and Hinckley.” The ‘kink’ in the parish boundary is at GR 631945.

The field paths are all well marked and in good condition. One point to note; Fleckney has crept slightly to the west since the map was last revised in 2010. The footpath now follows a modern street to GR 641940, where there’s a stile into the fields.

Further Reading

Either use OS Explorer 233 or, in the alternative, the Ordnance Survey offer an app at OSMaps.com. If you pay a subscription, you can access full OS mapping with familiar fonts and legends, but there’s a free version that is fine – it shows the footpaths and parish boundaries. You can clearly see the ‘kink’ you’re looking for.

‘Village and Farmstead: A History of Rural Settlement in England’ by C Taylor (George Philip, 1983).

‘Village, Hamlet & Field’ by Lewis, Mitchell-Fox and Dyer (Windgather Press, 2001).

‘Shaping Medieval Landscapes: Settlement, Society, Environment’ by Tom Williamson (Windgather Press, 2003) – Williamson is an academic at the University of East Anglia and the book includes a summary of the historiography of landscape history. I think it’s really well written, too; lucid, compelling, empirical, and very far from a theory heavy, ‘ivory tower’ academic text. Strongly recommended, as are other works by Williamson.

‘Leicestershire: An Illustrated Essay on the History of the Landscape’ by W G Hoskins (Hodder and Stoughton, 1957). Outdated (especially for the periods prior to the Roman Conquest and after their departure), and no doubt unfashionable in its tone for a vanishing rural England, it got me out on my bike whilst I was in the Sixth Form and opened my eyes to the palimpsest around me.

Web Resources

The best resource I’ve found for old maps is at the National Library of Scotland’s website

The 25-inch map of Kilby Grange Farm, surveyed in 1885 and published in 1886 is available here

You can find LIDAR images here

A parish boundary map is available at the walkingclub and the wheresthepath site is also a useful resource

Contact

simon@ballainsdale.co.uk

LIDAR Screenshot from the ARCHI MAPS UK website; LiDAR tiles © Environment Agency copyright and/or database right 2022.